“When you leave, come to me directly instead of going to the reception, okay?“, tells me the security guard of the Khorixas NWR rest camp as I am packing up.

It seems that Namibia has two kinds of accommodations: the private ones, in the hands of White Namibians, South Africans, Germans and other nationalities, and the NWR ones (Namibia Wildlife Resorts), belonging to a state owned company “mandated to run the tourism facilities within the protected areas of Namibia”. Places falling into the first category are often expensive and clean, with a good service (especially compared to my previous countries), confirming Namibia is doing very well in tourism (the country receives 1 million visitors per year, for a population of 2 million). On the other hand, I found places belonging to NWR being as expensive, but with a poor to average service. Well, a public service.

実は、この警備員は受付を通さずに、キャンプ料金を半分ずつにして私を通してくれようとしました。そうすればN$50節約できますね。次回来たときは、無料でキャンプさせてあげますよそれがナミビア流のフレンドリーさです…

今日は暑くて、コリハスを過ぎるとアスファルトは消えてしまいます。半砂漠と呼べるでしょう:水場の近くに放牧されている牛や砂漠象以外、何もありません。

There was no shop open in Khorixas and I am now going further on desertic roads. It’s very unlikely I find food joints from now on … and if I need to cook three times a day, I’m not sure I have enough pasta and rice in my panniers until the next town, Uis, four or five day from here.

After 30 km of gravel, I meet the most improbable shop! They have very little, no spaghetti, but a last 500 g pack of macaroni. I buy myself a little bit extra confidence. It looks like a good day so far.

But this lucky day is a short illusion: at one point, the wind makes my bike fall off the kick stand and breaks the bar-end mirror. It’s the 4th or 5th time. Five minutes later, it’s my rear tire: flat.

I can hardly believe I got a puncture on this nice gravel road. My tires are brand new and they are the quasi-puncture-less Schwalbe. I can see the tourism hut of the Petrified Forest less than a kilometer away, and some shade won’t be a luxury to investigate my tube.

I try to pump up several times my rear tire so as to be able to push it until the building. The slime tube is leaking its green drool inside the tire. I have there two problems: the slime pre-filled inner tube is of poor quality and is already cut open. And much more worrying, my new Schwalbe tire looks already old. It is almost the same as the good ones I used to have, except this one is the wired version, as the folding version was out of stock. Despite being always fully inflated, it shows black stripes that shouldn’t show that early. This is not a lucky day anymore.

Well, I superglue my bar-end mirror back and get rid of the slime tube for a normal air tube, I prefer that to an unreliable fancy technology. I am now at the Petrified Forest.

投稿 Petrified Forest on the map, I expected … a petrified forest. Namibian tourism is good at giving fancy names for its attractions. Here, the petrified forest is the site where a few fossilized trees are unearthed.

As I was expecting ghost trees standing up, I am disappointed, but the story of these trees is interesting. Pine trees (not endemic to Namibia) have been taken here a very long time ago from the closest rain forest (probably Congo, thousands of kilometers away) by huge floods and via the sea, that penetrated far inland at that time. They were buried down to 1000 m deep, and under the pressure, they fossilized. Erosion then happened and brought them to the surface again.

As a result, there are trunks up to 30 m long, made of stone, where the knots, bark and concentric circles are clearly visible. When the guide hits them with a stick, it sounds hollow. They are estimated to be about 280 million years old.

The water here is salty. The locals don’t drink it, they advise me to fetch it at another borehole. I find it not too bad, not as bad as the Senegalese water from the interior. There’s a lot of similarities between Namibia and the interior of Senegal! I keep this salty water for cooking pasta anyway. Or to drink, if I need. I don’t know which concentration of salt marks the limit between hydrating water and dehydrating water (apparently, an isotonic drink must have 4 times less salt than seawater, but I am still unable to determine that by tasting).

This road is the C39 leading straight to the スケルトン海岸. My initial idea was to go there. “The Land God Made in Anger“、“地獄の門” … I wanted to cycle there, among the shipwrecks and the skull & crossbones road signs. I am attracted by these desolate lands. However, I learnt that the Skeleton Coast is a protected area and one needs a permit to visit it. And this permit is not granted to motorbikers, and that some areas of extreme Damaraland can be traveled only in a convoy of 4×4.

As a result, I won’t be trying to cycle there, but will turn left to Twyfelfontein, an area with lots to see. The gate of the Skeleton Coast National Park is reached after a straight stretch of almost 100 km, and essentially, I don’t want to be turned down there and do 200 km for nothing.

But I think I understood why motorbikers can’t obtain a permit for the restricted area. You need to be sure you can get yourself out of any problem, else you could die. And similarly to game reserves, the extreme west of Namibia is home to desert elephants and desert lions. Desert lions are real lions in the wild, with no fences. They are tracked and their positions can be seen ここで: it is exactly where I would go! In addition, the day I passed in Otjiwarongo, a national newspaper featured Xpl-10 a.k.a The Queen, an old desert lioness who just died. The front cover was a photo of her attacking an adult giraffe, jumping directly on her back.

I am considerably more vulnerable than a giraffe, so if on the top of worrying about water, I must be prepared to counter lion attacks, it’s probably a bad idea to take the Khorixas – Torra Bay lonely road.

I leave the C39 for the D2612, another gravel road, in a very good condition, to the touristic location of Twyfelfontein. There is a small shop at the crossroads C39-D2612, but they only have bottled water. “Which water do you drink then?“。“Oh, we have to go to that farm with a borehole, but it’s far, far away …“. Well, I have enough water for the night, and I should reach tomorrow a lodge where I can refill.

Now away from the farmers’ area, it’s super easy to find a camping spot. I just walk 200 meters off the road and the land is mine. I ate only a pack of cookies for lunch, so a copious dinner (spaghetti with salt this time, thanks to the salty water boreholes) is my priority. But then, I realize how quiet it is.

I can hear only a few crickets afar. There is not a single gust of wind. No mosquitoes, no flies. No phone signal (which is rare). It is a shocking true silence, a silence so strong that I could believe I am deaf. I realize that a perfect sky full of stars, as special as it can be (you have to travel far away from civilization to avoid light pollution and be lucky with the clouds), is actually much more common than a perfect silence.

It’s indeed very rare to be at the same time away from all civilization, kilometers away from the nearest human or dog, and have absolutely no wind at all. Out of the hundred nights I have spent camping, I don’t recall hearing nothing, as there is always an insect, the movement of a leaf, the light buzz of a power line, etc. Tonight, it’s a true dead silence.

Although my feet need to breathe, I keep my closed shoes on. I almost walked on a small scorpion last night. Apparently, big pincers and narrow tail means painful like a bee sting, while small pincers and thick tail means hospital asap. I learnt funny stories on this journey, such as how to escape angry elephants (run up a hill, they can’t climb, or produce an engine roar if you are in a car), how to scare off aggressive baboons (clap in your hands to imitate a gun shot), and how to survive a crocodile after he already bite you (stick your hand deep into his throat until you open a flap that makes him swallow water)(works with sharks too)(in theory).

It is still quite warm, much warmer than in the Waterberg. For the same elevation, there can be a 10°C temperature difference between the different parts of Namibia. Tonight I spot the Big Dipper, from where I can guess Polaris, the Southern Cross, and Saturn. It’s night at 6 and I am in bed before 8 pm.

In the morning, I wake up for the sunrise and must cook and eat quickly before it gets too hot. On the road, trees are rare, so is the shade.

The interesting sites at Twyfelfontein are reached after a 12 km dead-end road. The nice gravel road takes me to a surreal landscape. The herbs are yellow, the cloudless sky is blue, and the mountains are red. It’s fantastic!

I am disturbed only by a few cars of tourists from time to time. Before visiting the lodge, refill my water and get a rewarding cold drink, I head to the rock structures.

The Organ Pipes designate the dolerite columns formed with magma cooling down in polygonal organization.

Next to the Organ Pipes is found the Burnt Mountain, or Verbrande Berg in Afrikaans. The description reads that “here assorted shales and basalt have been continuously baked by the suns heat into vivid shades of just about every colour except green. The scene is unique and unlike anything else on earth. In ages past the area was blasted with an eruption of basalt. It cooled and left these lovely colours and strange rock shapes“。

それ reminds me of Iceland, in the region of Myvatn. Unique rock formations, extraordinary colors and no population. Twyfelfontein was well worth the detour.

I spend a lot of time shooting videos there. Pictures and videos don’t do justice to the unusual colors, it’s a magical place. I was thinking of making only a short day-trip here, but I end up staying for the whole day. There is a campsite where I will meet again the first cycle tourers I have seen since Dave in Angola, a couple from Belgium.

The area is also home of desert elephants, wandering freely between the red sandstone cliffs and the waterhole of the Twyfelfontein lodge. I see one, when other people report that a group of six was close to the road.

My water is over. I didn’t refill since yesterday morning. But before heading to the lodge for a cold drink, I decide one more time to see what’s around the corner of that road, and without any sign, it is where the rock engravings are hidden.

Twyfelfontein means in Afrikaans “doubtful spring”. In this very remote place, a German farmer called Levin stopped in 1946 and tried to develop his cattle during twelve years with this unreliable spring, before quitting after a severe drought.

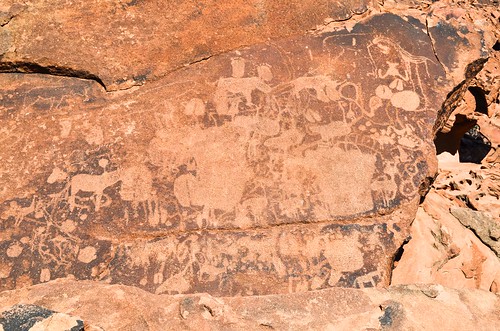

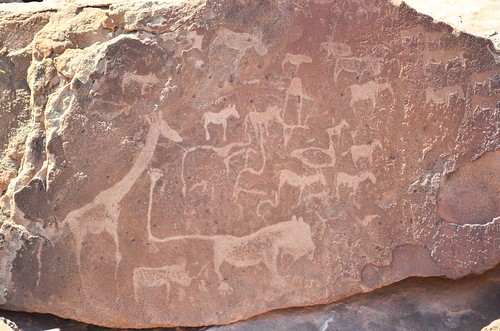

However, more than 2000 years ago, the place was less hostile and the Khoisan (bushmen) inhabited it with more animals than today. They left engravings in the sandstone representing animals, water holes, and their traditional ceremonies.

The presence of penguins and sea lions (for such a desertic location) reveals that bushmen knew these animals and had been to the coastal areas.

I cycled only 50 kilometers today, but the sun constantly burning my face makes me feel it’s much more. Behind one on these hills made of boulders is quietly concealed the Twyfelfontein lodge, with green grass and a flowing fountain.

Wild ostriches cut my road as I take a deceiving shortcut via a sand track. Workers at the UNESCO engravings site told me there is a location (township) near the campsite with small shops. Really?

A shop would be welcome. I am still carrying too little food for these kinds of roads. The campsite employees confirm it to me: there is a location behind the telecom antenna.

And indeed, less than a kilometer away from the touristic institutions, subtly tuck away behind another hill, all these people working at the lodge and as guides live in simple houses and shacks. I need to buy food and luckily they have cans and pasta there, but for sure, this place is not meant to be found. You would think there is nothing in this beautiful desert but wildlife, and it’s not the case.

Namibia seems to be still organized today on an apartheid model. Whites own almost every big business, they run the workshops, supermarkets, hotels, large farms, while most Blacks live in townships and have the unqualified jobs.

Broken glass is everywhere on the floor, big ladies are drinking with loud music, that’s the real Africa that would tarnish the image Twyfelfontein conveys. But once again, the only way to survive out in the scenic but bare land of the Whites, without a 4×4 loaded with food, is to find where Black people live.

I am truly grateful to the holder of this web site who has shared

this great paragraph at at this place.