Más de la mitad de toda la población de Namibia vive en Ovamboland, en sólo el 6% del territorio. Lo Ovambo son por lejos el mayor grupo étnico del país y el término Ovamboland (unpatriaterritorio reservado a los negros bajo la política de apartheid) todavía está en uso a pesar de la división administrativa de post-1990. Para llegar a Tsumeb de Opuwo (Kaokoland), tengo que cruzar esta región de oeste a este.

Me tomará aproximadamente 6 días de 600 km, ya que la carretera es asfaltada y directo. A ciclismo en el lado norte de la Parque Nacional de Etosha, esta enorme reserva de caza que no se vuelva a encender (como todas las áreas marrón aquí, accesible sólo con un permiso o si pertenece a De Beers).

Como salir de mi tienda, disfrutando de los primeros pasos bajo el sol naciente del hermoso día por delante, tienen esa sensación de que me observaba. Algo se movió en las rocas. Oh y ahora una pequeña cabeza apareció y se escondió otra vez. Después de la observación más cuidadosa, me doy cuenta hay una docena de marmotas que me mira. No niños de este tiempo, sólo las marmotas.

Una vez en el camino, me doy cuenta de pronto el paraíso ciclismo namibiano, que yo tanto estaba esperando, no será como lisa y tan interesantes que me imaginaba. Es muy caliente, no es fácil encontrar agua, y el viento es contra mí. Conservé conmigo el bidón de 5 L por lo que llevo ahora 10 litros de agua. ¡Es de 10 kilos extras! Mi camino para los próximos seis días es bastante sencillo: este. Me dijeron un viento del este no significa lluvia, es bueno, pero estos segmentos larga rectos sin otra cosa que viento en contra pueden ser presionando.

Camino agradable, tar agradable, poco tráfico. Muchos Pick-up Toyotas conmutar entre los distintos pueblos de la región, y los pasajeros están de pie en la zona de carga. A 100 km/h, parece muy fácil para algo malo suceda a ellos. Por otra parte, los cascos son obligatorios para los ciclistas!

Rápidamente el viaje es aburrido. No hay nada mucho que ver o hacer. En el cruce entre C41 y C35, en un pequeño asentamiento que parece del lejano oeste, puedo comprar carne y patatas fritas, mucho mejor que fufu y peces! Hasta ahora era saludable (tal vez... No estoy todavía seguro comer yuca cada día ser más saludable que la carne y patatas), y ahora va a ser gordo y sabroso! Sin embargo, todo el mundo dice que no hay agua aquí (luego lo que es que todos bebiendo?) hasta que una señora me lleva a su casa a llenar mi tanque de 5 L, que había terminado en sólo una mañana. El agua no es lo que limpia, debe ser procedente de un pozo cercano. De ahora en adelante, es cada vez más aburrido. Puedes ver en el anterior, bikemap que 100 km línea recta larga a Okahao es mi camino, sin ninguna sola vuelta. Como en el Sahara, mi duele butt. Ocurre cuando el camino es tan recta y plana que mi posición sobre el sillín nunca cambia.

Dejar de poner mi tienda cuando veo un tanque y grifo cerca de una granja, por lo que puedo de la ducha con agua de vaca. Esta parte de la tierra está vacía de casas, pero hay ganado por todas partes. Parece una fábrica de Chuletón de buey natural extensa, pero en una etapa muy temprana del desarrollo para mi estómago.

Todavía es muy aburrido y muy caliente: 66 kilómetros rectos hasta el siguiente pueblo, Okahao.

Okahaois the largest town in the area with a mere 2000 inhabitants. As I’m still new in Namibia, I keep comparing it to where I come from: this town has more large businesses than a city of 100’000 in Congo, Cameroon, Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon … Ah no, Gabon has only two cities over 100’000 and I’ve not been there. Two supermarkets (Shoprite and Woermann), a plethora of fancy Chinese shops, construction material warehouses, banks and ATMs, … it looks quite impressive to me. The downside is that all the shops are indoor. There are no ladies selling basic stuff, vegetables and food by the road side. The absence of street sellers, the white sand on the sidewalks, and the fact that most of the people travel in old rusty Toyota pickups instead of walking, make it feel like a different continent from Angola and above.

There’s many bars and shebeens, and the old keep drinking through the day. It doesn’t look like fun life. Boys wear winter hats and ladies walk with umbrellas to protect their skin from the sun. The proximity of South Africa is great, it’s plenty of good food from there. I can buy a real mango juice for 80 cents a liter, instead of the 4 USD ones imported from Turkey or the UAE sold in the expats supermarkets of Cotonou or Pointe-Noire. I can splurge on good products, compared to “before”, when I would find a rare supermarket and buy only one or two items to remind me how cheese and chocolate taste like.

M

¡Y se siente tan bien! Nuevos zapatos después de mucho tiempo con zapatos rotos. Es como encontrar un puesto de comida a un lado de la carretera después de muchas horas pensando en comida. Todos mis placeres son muy simples: comida después de la inanición, agua después de labios secos, equipo muy necesario después de un largo tiempo de incomodidad, etc. Y estos placeres son realmente más intensos que aquellos considerados como difícilmente accesibles. Me recuerda a algunos textos de Sénecaque estudié en las clases de latín en la escuela.

Todavía estoy disfrutando de mi nueva buena vida y termino comprando demasiada comida, no puedo cargarla. Si trato de comer y beber lo suficiente de mis compras para que el resto quepa en mis alforjas, entonces mi barriga está demasiado llena y no puedo pedalear más. Ah, qué dilema ...

Este fabricante de blicks se encuentra junto a una tienda botore. No estoy en Japón, pero está lleno de engrish!

La razón por la cual la tierra está tan húmeda a mi alrededor, mientras que estaba súper seca hace 100 km, es porque paso cerca de la charca de Etoshajusto después de la temporada de lluvias. Todos estos pantanos están llenos de agua que proviene de Angola y del río Kunene, y que va hacia la charca de Etosha sin alcanzarla.

Incluso parece tropical con las palmeras. El hecho es que todavía estoy entre los trópicos (23'26°N -23'26°S), pero al igual que la mayor parte de Mauritania y Malí, que rara vez se ajustan a la imagen de países tropicales. He visto fotos de esta área cuando está seca, y se parece mucho más a la Mauritania del sur. Hay muchas pequeñas aldeas junto a la carretera, compuestas de casas de ladrillo simples, la mitad de las cuales son bares.

Los últimos cuarenta kilómetros hasta Oshakati, one of the largest cities of the country with a population of 40’000, are flat and fast. I arrive straight into the commercial area: Game, Mr. Price, Clicks, Ackermans, … all major South African retailers are here. The greetings also remind me of South Africa. One must systematically ask “¿Cómo estás?” to the shopkeeper, cashier or customer, which will be answered with “I’m fine and you?” and then “fine thanks“. It’s so mechanical that I could answer “cassoulet” to the first question, the other would still say “fine thanks“.

Yes, that’s definitely the end of the wild adventure, I’m on a shopping mall parking. Leaving my bike with all my stuff in front of a large mall while going into the maze of shops makes me uncomfortable. There are just the useless guards, difficult to trust. Yet, I can’t leave this place without a new air mattress. I get a cheap one for 18 USD, almost the same I got in Angola for 50 USD, so I can get rid of it and its four patches. Next stop: food. There is a Wimpy burger at the Engen gas station, great! I’m going to enjoy a rare fat burger. But it’s quite expensive and not as good as in my memories. Watching through the window, it could be like South Africa. Some prices are even labeled in rands (there is a one-to-one parity between the rand and the N$). I hadn’t seen many White people so far, but here they come. Big shaved head, big belly, a check shirt tuck in short shorts, and high socks in boots. A peculiar definition of sexy. On the other hand, some Black security guards, sitting in the shade all day long and getting paid for it, ask me for 5 dollars because they are hungry. Excuse me, I am the one who cycled 230 km since Opuwo with little food on the way and I’m really hungry.

Todos los edificios y tiendas solo tienen un piso. Todos se mueven en coche. No hay encanto en este lugar. Todos están vestidos como en cualquier otro lugar con ropa occidental. No me siento bien en la jungla urbana. Solía dejar mi bicicleta en cualquier lugar para ir de compras o dar un paseo, pero aquí hay demasiada gente y necesito adaptarme al desarrollo. Es como la Europa impersonal donde no dejarías tu bicicleta sin atar en un pueblo. De hecho, nunca he usado mi pesado candado desde que llegué a África, ha sido un peso inútil atado a mi tija del sillín. Al principio, lo bloqueaba en tiendas o por la noche cuando acampaba en la naturaleza. Pero rápidamente resultó innecesario: la gente no la robaría. Y estoy casi seguro de que nadie puede manejar una bicicleta de turismo completamente cargada y pedalear lejos sin práctica. Siempre me sorprende lo pesada y dura que es después de 10 días de descanso fuera de la carretera.

El tráfico ha estado muy tranquilo hasta aquí, y es un infierno andar en bicicleta en Oshakati. Los dos carriles por dirección son justo lo suficientemente anchos para dos vehículos y no dudan en acelerar, pasando súper cerca de mí. Ondangwa es otro pueblo grande a solo 30 km después de Oshakati, y tengo que andar en la carretera de entre ambos lo más rápido y seguro posible.

En lugar de acampar en el monte, me decanto por el camping del museo Nakambale, con electricidad, ducha caliente y una cocina. Un poco de comodidad se siente bien.

El campamento Nakambale fue inaugurado por la esposa del ex presidente. Al igual que el supermercado Shoprite de Oshakati, que fue inaugurado en 1996 por Sam Nujoma, el primer presidente de Namibia, en funciones desde 1990 hasta 2005. Por cierto, el 100% de los (dos) presidentes namibios tienen una barba genial. En un país con una población de 2.1 millones, supongo que es fácil tener al presidente en cada evento.

El museo Nakambale rinde homenaje al misionero finlandés Martti Rautanen, uno de los primeros en Namibia. Como resultado, el museo está lleno de artículos finlandeses y ovambo. Martti Rautanen vivió en la aldea de Olukonda desde 1870 hasta su muerte en 1926, aprendió Ndonga y tradujo la biblia.

De Ondangwa hasta Tsumeb, son aproximadamente 275 kilómetros de carretera aburrida. El mapa de arriba no necesita palabras: ni un solo giro y perfectamente plana.

Los coches todavía me pitan como si no perteneciera a la carretera y me adelantan de manera peligrosa. Esperaba mejores modales de los namibios. Lo que realmente me sorprende es la presencia de muchas tiendas y puestos de comida junto a la carretera. A pesar de la baja densidad poblacional, es fácil conseguir fish & chips y una Coca-Cola cada 10 o 20 km. Incluso hay pequeños supermercados en pequeños asentamientos.

La electricidad hace posible obtener una Coca-Cola fría y papas fritas calientes en los pueblos, es fantástico. Como elemento de comparación, el 98.9% de todos los hogares brasileños tienen acceso a electricidad, el 99% de toda la población china, y 11 de los 28 estados indios tienen una tasa de electrificación rural superior al 80%.Wikipedia Los estados, por otro lado, indican que, en 2012, menos del 10% de la población rural en África subsahariana tiene acceso a electricidad.

Como consecuencia del desarrollo, para mí, como visitante, siento que no hay más encanto y aparentemente no hay cultura, en comparación con mis lugares visitados anteriormente. Todo el mundo está vestido de occidental, los edificios son montones de ladrillos sin interés, la comida es comida rápida (papas fritas en el microondas con salchichas o pescado congelados). Poca o ninguna personalidad. No hay mujeres que lleven cosas en la cabeza, no hay comida afuera, mucho concreto y alquitrán, y omnipresencia de cerveza.

I don’t know how to explain it, it just doesn’t fit with the Africa I have experienced until now, and it feels strange. I didn’t have this feeling in Accra or in Dakar. Maybe it’s too quiet here? Too clean? Perhaps it’s the fact that rural places have the good infrastructure of a city, and there’s no “village feel” anymore?

¿Quizás es porque ya no es tan aventurero? Los cajeros automáticos están en todas partes, las tiendas pequeñas aceptan tarjetas de crédito, no hay sorpresas sobre qué comida esperar en el próximo pueblo. Las cosas son tan predecibles. La red es buena, tengo señal en todas partes. Internet es rápido, incluso en 2G es mejor que el 3G de algunos otros lugares. Debería estar feliz de estar de vuelta en el primer mundo, pero la admiración inspirada por la buena infraestructura es rápidamente reemplazada por el aburrimiento …

Puedo medir lo interesantes que son mis días con el número de fotos que tomo. Alrededor de 80 para un día promedio, más de 120 para un día escénico, y alrededor de 25 para un día aburrido. Estos días son más como 20. La carretera recta y aburrida me hace parar cada 20 kilómetros (es decir, cada hora) para descansar mi trasero y beber una botella de coca-cola de 1 L helada.

La tierra es plana y adecuada para acampar casi en cualquier lugar, pero encontrar un lugar para acampar es complicado. No puedo simplemente esperar al atardecer y esconderme a cien metros de la carretera. A pesar de la escasa población, todo está cercado. Hay cercas a lo largo de cada carretera. Si esto continúa así (y me dijeron que sí), será preferible pedir permiso en una granja para entrar.

En los shebeens, la gente bebe mahangu, una cerveza hecha de mijo. Es como el equivalente al vino de palma. Por otro lado, las palmeras de Namibia, el makalani, se utilizan para hacer licor fuerte. También se puede usar la fruta de marula para hacer cerveza, pero no es tan sabrosa como amarula.

Casi todos los pueblos comienzan con la letra O: Pasé por Opuwo, Okahao, Oshakati, Ongwediwa, Ondangwa, Omuthiya, y ahora estoy en Oshivelo.

A pesar de todos los licores caseros disponibles, me aferro al litro de coca-cola fría para mis descansos en bicicleta. La carretera plana y recta va rápida, puedo completar mis 100 km diarios en 5 horas de esfuerzo, permitiéndome hacer muchas paradas. Y descansar mi trasero.

En un shebeen, un hombre de negocios local me dice que ¡la gente es pobre y el gobierno es rico! ¡Solo somos 2 millones de namibios! Si le dan solo 1000 dólares mensuales a cada uno, funcionará.“.

Supongo que se refiere a 1000 N$, es decir, 100 USD. Puede ser posible, al igual que en todos estos países ricos en recursos, donde el GBP per cápita es diez veces más que el salario anual promedio (si es que hay alguno). El concepto de 'el gobierno debe proveer' se entiende mucho mejor que el concepto de ganar dinero. Varias veces, sentí ganas de molestar a la mujer que dormía en el mostrador cuando pedí una Coca-Cola.

En estas largas carreteras, escucho que mi cadena cruje, a pesar de haberla limpiado y lubricado con cuidado, como cuando la anterior se rompió... ¡No es normal que tenga que reemplazarla tan pronto! Bueno, esta vez podré comprar una buena nueva en las tiendas deportivas de Namibia.

Sucede muy poco, excepto un Toyota blanco que conduce demasiado rápido y toca el claxon al adelantarme demasiado cerca. El coche dice 'Policía'. De todos modos, no puedo hacer nada contra esto ...

Desde que pasé Oshivelo, no hay absolutamente nada en la carretera, ni una sola casa. En Ovamboland, había bares cada 5 o 10 km hasta ahora. ¿Cómo es que ahora está tan vacío? Acampo cerca de la bifurcación al Parque Nacional Etosha, sin haber visto ningún animal salvaje. Solo vacas.

Me di cuenta más tarde de lo que sucedió. Cuando salí del pueblo de Oshivelo, había un control, un 'control veterinario'.

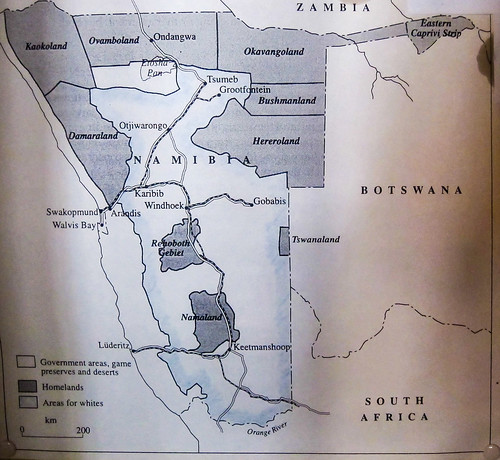

De hecho, señaló la salida del VCF, el Veterinary Cordon Fence, also called the Red Line of Namibia. It is a physical fence to, originally, separate the Blacks from the Whites. apartheid was practiced not only in South Africa, but also in Namibia. Though I was told it was not “that bad” here, where “bad” could mean Blacks can’t leave the boundaries of their homelands without papers in order, and probably worse things …

This map explains why, still today, the small Ovamboland gathers half of the Namibian population. The population density there is 10 /km2, five times more than the country average.

The Red Line evolved into the VCF, to avoid movements of cattle between the “north” and the “south”, preventing the diseases from the north to contaminate the south. It is true that on the northern side, the cattle is roaming freely everywhere, whereas in the south, the White farmers keep the livestock within fences. I have seen cows and goats eating trash, paper, cardboard, plastic bags and even chewing on PET bottles. Well, I have seen that in India too. The meat produced in the north is not allowed for sale anywhere but in the north, while the meat produced in the south can be sold anywhere and exported.

Lo que me sorprende es que, 24 años después de la abolición de las patrias, la cerca sigue en efecto y la carne del norte no puede venderse en otro lugar. Y que no hay una sola casa, un solo shebeen, en 80 km entre Oshivelo y el lago Otjikoto.

Desde que dejé mi campamento, no he visto una sola casa durante 60 kilómetros. Solo cercas y el ferrocarril. La lluvia me golpea y no tengo dónde refugiarme.

La lluvia se está intensificando, cayendo casi horizontalmente empujada por un viento fuerte, y lo único que encontré fue un árbol. La niebla invadió la tierra y el viento es lo suficientemente fuerte como para hacer que mi bicicleta se caiga del caballete. Incapaz de ver algo y de conducir, algunos autos se detienen. En unos pocos minutos estoy completamente empapado, de la cabeza a los pies.

No puedo hacer nada más que esperar que no dure demasiado. Hace frío. Debo llegar a Tsumeb esta noche, está a 40 km, y definitivamente necesito encontrar un lugar seco. Me subo a la bicicleta después de que pase la lluvia. El viento secará mi camiseta, pero mis zapatos siguen siendo como un baño para los pies. Veinte kilómetros antes de Tsumeb, me detengo en el lago Otjikoto, a sinkhole lake with lots of history.

Namibia was first colonized by the Germans. It started in 1882 when the German trader Lüderitz started to buy land on the coast, the little African land remaining unoccupied by other European superpowers. By 1884, he involved Bismarck who would declare present-day Namibia as África del sudoeste alemana. During the World War I, Germany lost its colonies (incl. Togo, Tanzania, Cameroon) to the French and the British. For the case of South-West Africa, the then Prime Minister Louis Botha informed the British that South Africa was strong enough to defeat the Germans. They were allowed to, and they did(and then occupied Namibia until 1990 against UN decisions). During the defeat, the German soldiers dropped their weapons into the Otjikoto lake.

Nadie sabe qué tan profundo es el lago. Los buceadores nunca llegaron al fondo, pero estiman la profundidad en más de 145 m (para un diámetro de 100 metros) (Mapa). Sin embargo, lograron sacar a la superficie en 1983 algo de artillería alemana que estaba allí desde junio de 1915. Los cañones recuperados se pueden ver en el museo de Tsumeb, y se ven en muy buenas condiciones.

También se dice que hay una misteriosa caja fuerte con oro en el fondo…

Para cuando quiero subirme a la bicicleta nuevamente para llegar a Tsumeb, la lluvia regresa. La gente en la pequeña oficina del lago ofrece que acampe en el almacén, y también encuentro que es mejor que llegar empapado a una ciudad por la noche.

Estas personas son Damaray hablan khoekhoeg, un idioma con clics. Les pido que me enseñen a contar, pero rápidamente me rindo. Las palabras para uno, dos, tres, cada una contiene un clic diferente. No puedo explicar lo ridículo que suena si lo intento, así que aquí hay un video para autoaprendizaje. Los ganadores pueden ir a bailar.

Siempre que hablo de Angola, donde teóricamente los namibios pueden entrar sin visa, los namibios siempre responden que nunca van allí. La policía es demasiado mala y es demasiado arriesgado visitar. Nunca me han pedido sobornos en serio allí, pero no me sorprendería si abusan de sus vecinos. Sin embargo, el pueblo Kwanyama del sur de Angola, en la provincia de Cunene, son iguales que el pueblo Ovambo de Namibia.

El lago también tiene los restos de una antigua máquina de vapor que solía bombear agua.

Espera un poco a que mis zapatos terminen de secarse, dejo los saltamontes y completo los últimos 20 kilómetros hasta Tsumeb. Dave me dio un contacto allí.

Tsumeb es un pequeño pueblo minero en el norte de Namibia. Es bien conocido por su rica mina, ahora cerrada, de la que se extrajeron cobre, plomo, plata, oro, arsénico y germanio.

Desafortunadamente, mi contacto no está allí en este momento. Deambulo en busca de alojamiento barato, pero todas las opciones están llenas (y demasiado caras de todos modos). Mientras como una hamburguesa de pollo (tengo mucho que ponerme al día, nunca pierdo la oportunidad de comer una hamburguesa en una comida rápida), contemplo la idea de salir ya de la ciudad e ir de campamento. Dando una última oportunidad a Tsumeb, me encuentro con el Etosha Café, donde hay wifi y habitaciones asequibles. ¡Eso es todo lo que necesito! En este momento, no sabía que acababa de entrar en el mejor lugar de la ciudad, y es el comienzo de un largo descanso ...

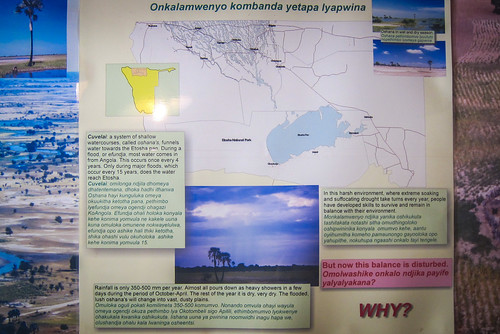

Up to 60% of the Namibian population, comprised of Aawambo (or Oshiwambo speaking people), is densely located in the socalled ‘Ovamboland’ in the central northern regions of Omusati, Oshana, Oshikoto and Ohangwena. From my point of view as an Environmental Consultant the main reason for this is the Cuvelai wetland also known as the ‘Oshana’ drainage system. As it is well known Namibia, like most of Southern Africa, is arid with very limited surface and groundwater resources. The only perennial rivers (Zambezi, Kavango, Kunene and Orange) are shared with other states. So for it is rare to find a single densely populated area without any a water resource support ecosystem. The Aawambo are said to have originated from East and central Africa; they migrated from there and settled in and around the Cuvelai wetland 200-400 years ago. Since then they continued to live there and protected their domain land from foreign invaders; first German settlers and later South African occupants.

El humedal Cuvelai proporciona a los Aawambo servicios ecosistémicos como agua para el cultivo de mijo y el ganado, peces y aves, y madera. La producción de mijo y el ganado (principalmente vacas) son pilares de la economía de los Aawambo. Durante muchos años, la producción de mijo y el ganado sustentaban la vida lujosa de los Reyes, que podían tener hasta 10 esposas y hasta 50 hijos. Incluso un hombre adinerado ordinario podía poseer hasta 200 vacas sin tener conflictos por la tierra de pastoreo con otros pastores.

Es evidente que en aquellos buenos tiempos, el humedal Cuvelai solía ofrecer tierras de pastoreo favorables en comparación con su estado actual.

Fuiste muy afortunado de haber realizado tu viaje entre 2012 y 2014, cuando las temporadas de lluvia fueron buenas en esos años en particular. En este momento, el humedal de Cuvelai está completamente seco, habiendo experimentado sequías extremas en 2015 y 2016. Se espera que estos períodos de sequía aumenten y duren más de lo habitual debido a los impactos del cambio climático. Enfrentando estas difíciles condiciones climáticas, los pequeños agricultores en áreas remotas de Ovamboland están abandonando lentamente sus formas tradicionales de cultivo. Esto incluye la modernización de su modo de vida. Desafortunadamente, en el proceso, también están perdiendo sus culturas.

Esta es quizás la razón por la cual el desarrollo es tan rápido en la zona, como se evidencia en tu narración:

Lo que realmente me sorprende es la presencia de muchas tiendas y locales de comida a lo largo de la carretera. A pesar de la baja densidad de población, es fácil conseguir un ruso con papas y una Coca-Cola cada 10 o 20 km. Incluso hay pequeños supermercados en poblaciones pequeñas.

A menudo, como personas locales, rara vez notamos esto ya que nos hemos dejado llevar por la vida moderna y quizás nos relacionamos menos con nuestras culturas. Estas son quizás algunas de las difíciles realidades con las que tenemos que lidiar al enfrentar el cambio climático y encontrar pilares económicos alternativos.

Realmente una observación profunda y precisa de las tendencias experimentadas por el pueblo Aawambo a lo largo de los años, Twali.

I loved JB’s review of north-central Namibia. As someone passionate about observing how people use and relate to spaces, I found so much richness in the description of his experiences and the entire narration of his Ovamboland experience through his photography.

Fue una forma de narrar tan creativa, y JB, ¿qué sentidos tan agudos tienes?! Definitivamente deseo que muchos namibios lean tus reseñas, porque hay tanta importancia en lo que discutes, pero como pueblos indígenas, a menudo estamos atrapados en la vida para notar todas estas observaciones. Quiero decir, has estado en una mejor posición para comparar tu experiencia en Namibia con el resto de los países africanos, así que quizás tus reflexiones son lo que los namibios necesitan para darse cuenta de lo que debemos priorizar de cara al futuro.

Por cierto, fue una lectura tan genial. ¡Lo disfruté! Sentí que era parte del viaje. ¡Por más lecturas divertidas, salud!

¡Gracias Max!

Realmente me encantó Namibia, estoy deseando regresar y ver cómo las poblaciones se han movido a lo largo del tiempo y los lugares.

PD: Mi lente DSLR era solo la Nikon de nivel de entrada 🙂