During lunch, I ask the captain “and what if I fall off the ship without anyone noticing?“. It’s not like taking a plane or a bus. Here, I can take in as much luggage as I can fit in my cabin, nobody checked what I was carrying, and I can jump off the boat anytime.

He answers that most likely, people would start to worry after I miss a second meal in a row. I got a call once when I was waking up too late for breakfast, but the steward would not disturb me too much. After all, I’m a tourist paying for the slow and tranquil travel. It means that if I fall in the Atlantic ocean in the middle of the night, it could take more than 12 hours before the vessel crew is sure that I disappeared. They would then trigger an emergency alert and make a U-turn. It means it’s up to me to survive up to 24 hours in the ocean … is it possible?

The captain says that in 30 years of experience, he never witnessed such an accident. If I want to secretly jump off the boat and kill myself, I’d have no problem. If it’s windy and wet outside, and if I behave carelessly, it could reasonably happen.

But then, what about the work and the crew? With the amount of vodka on board and the type of work, I can easily imagine deckhands coming to blows, and plouf!, in the water. But when the crew is on the deck, for maintenance or repairs (there is always something to do), they are teamed up so that in case of an accident, someone can trigger the alarm. While drinking, they are apparently extremely aware of what not to do.

The captain says he’s responsible for the ship and everything on it. Priority follows that order of importance: first, the people, then the vessel, and at last, the cargo.

After Walvis Bay and in the open sea again, I follow my pre-breakfast gym training routine. I hate gyms, but that’s my only option to sweat here, since I can’t move further than the living quarters and the bridge. The refrigerated containers we loaded in Namibia mostly contain frozen fish. We’re now sailing at 17 knots instead of 11.5, because the ship received the order to arrive in Vigo a day and a half earlier. From now on, we head straight to the next waypoint, off Cabo Verde. There is absolutely nothing happening on this route: it’s water and just water. There’s not even another ship showing up on the radar. The 2nd officer tells me that two interesting phenomena could occur: mirages (boat upside down in the sky) and receiving the radio from Banana Wharf (DRC, on the north bank of Congo River’s mouth, that I saw from the chatta), despite being 200 or 300 km at sea.

Since we’re sailing through the gulf of Guinea, the chief mate tells me stories of West African ports, like Conakry or Lagos. When they were there, they had to offer thousands of dollars to agents do their work there. It goes directly into the pocket of the agent, so it’s indeed a compulsory bribe. On the other hand, paying taxes to official authorities or to the government, that would keep it in the hands of the few connected instead of redistributing it to the people or building infrastructure, isn’t fundamentally different.

The shipping company knows that it always happens, so the captain gets a “cash advance for bribes” when the vessel is going to dodgy ports. They say all shipping companies, including big ones like MSC and Maersk, do it too, because there is no way of escaping bribes: the coast guard would first come on board to ask their presents, then the immigration, then the customs, then the police … It’s just like the checkpoints my roads! The difference is that, unlike me, they can’t say that they are poor, and they can’t wait. They must pay to be allowed in the port. Just like on land, one of these agents will find a problem in a perfect ship with all papers in order if bribes are not paid. On the other hand, a dangerous rusty ship infringing all possible laws will be allowed in port and at sea if the captain hands out the right presents. If they don’t pay, the customs/police/immigration/health will just prevent the ship to enter the port, and that’s simply an impossible consideration for a shipping company that has to do business.

So, what’s worse than Africa? Without hesitation, the chief mate answers “ports of Ukraine and Russia in the Black Sea“. There, negotiation with the police in a cabin is not even possible. With Africans, it’s always possible to take an officer in the ship shop and give him alcohol, cigarettes, or argue about a reasonable amount of money. With Ukrainians/Russians, the police chief would go on board ask straight for 5000 €.

These long days at sea, where the only thing in the landscape that is moving is the sun, are perfect to edit my videos. I compile Sierra Leone and West Africa 2, and find time to watch one of these super popular movies that was missing from my film education: Top Gun. Hmmm … popular doesn’t mean good.

Today is Saturday, and at eighteen hundred, it’s barbecue time. Seafarers have installed tables on the D deck and the chief cook is braaing. He has two lamb legs roasting and skewers with beef and prawns. It’s a new idea for the Ultimate Braai Master TV show: a braai at sea 500 km away from the closest land. It’s a bit of a fight to get a space on the grill, but alright. I’m surprised the lamb is from Germany. With all that cheap and delicious South African meat, why didn’t we refill there instead of eating German meat that has already spent 50 days at sea? Company policies. Well, it already tastes much better than a potato goulash, so I can’t complain.

I learn that a 23 year old seaman, in his 4th year of study to become a captain, earns 1500 euros per month. It’s a very good deal for a German employer, and a very good first salary for someone living in Poland. So why are so many seafarers from Poland and the Philippines? For the Poles, they are (as I am told) as good as Germans but much cheaper. Filipinos have a special history. In the past, one big shipping company had decided to build its own maritime academy instead of relying on graduating students. They built it in the Philippines. It appeared to be a good idea, so it has been copied, and today Filipino seafarers have their own Wikipedia entry.

But they are not worth the same. From the mouth of a German, if you operate your ship with a Filipino crew, heavy repairs will have to be planned within 5 years. With a Polish crew, or at least a Polish commanding team, the vessel will be spotless after 25 years. The words are rude, but it seems it doesn’t even matter, since maritime companies prefer ordering new vessels rather than maintaining their existing fleet. In the last 10 years, the world fleet by tonnage nearly doubled. Some say that there are too many ships now, and when recession hits, it costs too much to operate.

I also learn that our ship (multipurpose) costs 24000 € per day for rental, while a Maersk simple container ship is around 7000 € per day. By the way, www.marinetraffic.com has become one of my favorite geek websites. They display all merchant vessels with their destination and a few details about the ship (length, deadweight tonnage, type of cargo, year of built, flag, etc). It’s a great animation of globalization in action, especially when zooming on the Channel or the Singapore Strait. Since I allow myself to quote Wikipedia, “merchant shipping is the lifeblood of the world economy, carrying 90% of international trade“.

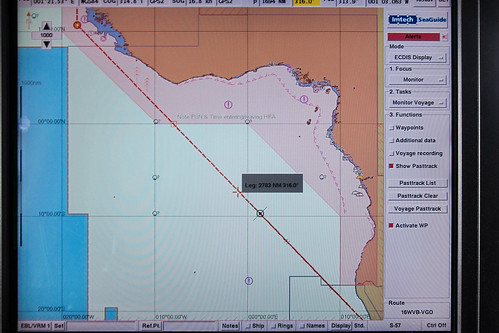

The GPS on my phone cannot catch any signal. On my N900, it’s usually pretty good even without the A-GPS, so I don’t know why it doesn’t work in the ocean. The ship uses the same GPS satellites, and of course it works. Anyway … the navigation system above shows the HRA in red, the High Risk Area. Just like with the governmental travel advice websites and their red “no go” zones, it’s fairly exaggerated. Pirates would generally stay close to the coast and not 500 km away on the high seas. Our route will take us through the HRA close to Sierra Leone and Liberia, but we’re not getting close to Nigeria.

Being sailing in the “armpit of Africa”, I can observe the metaphor both geographically on the navigation system and meteorologically on my skin: I’m sweating just by standing outside on the deck. I can feel the warmth, since we’re only at the latitude of Luanda (9°S), 1000 km offshore. We’re now definitely away from the dry Southern Africa and getting back into the damp central region. It reminds me of the cycling in Cameroon and Gabon, it was an open air sauna.

Apparently, we transport uranium now, it’s on the list of dangerous goods pinned on the bridge. Since I visited the Rio Tinto Rössing mine in Namibia, and cycled past many other uranium mines in the Namib (blog post), it’s not a surprise our stop in Walvis Bay brought us more than marble. I’m liking this journey even more, since I feel directly involved with international trade, be it trains, high voltage transformers, manganese and chrome, uranium or frozen fish. It’s more real than in an office behind a computer.

Naturally, I try to spot radioactive symbols on containers, from any angle possible. One barrel of yellow cake provides the same energy as 40’000 oil barrels, so the containers with them inside must be the most precious containers of the ship. However, the chief mate tells me they are transported in standard 20-foot containers, so there is no way to spot them. There could be a way … all containers have a unique ID starting with four letters. It’s ISO 6346. The chief mate has noticed numbers he has never seen before, and it’s the uranium. He also tells me he was given a Geiger counter “just in case” …

Every day, the chief mate, 2nd officer and 3rd officer take the same 2 x 4 hours shifts. The chief mate does 2000-2400 and 0800-1200, but the two others have a screwed up sleeping pattern. After his shift, the 2nd officer takes me on the bow. It’s 200 meters ahead of the bridge, on the other side of the containers. It’s where Di Caprio shouts “I’m the king of the world“, and it’s very quiet. The ship is breaking small waves just below. I put my head inside a through hole in the hull to see the anchor hanging, but I don’t feel confident there.

I am explained how to change an anchor at sea, but it’s very complicated. It could happen that the chain gets stuck between rocks on the seabed. In that case, the crew would detach and abandon the anchor by cutting off one of the red chain links. But attaching a heavy spare anchor from outside the hull, without external assistance, is a different kettle of fish. I will probably won’t see the anchor in action, since it would happen only if a port refuses access to the ship at the last minute. If a port has no berth available for us, we’ll try to know it in advance and reduce speed, so as not to have to anchor the vessel.

We also climb up one of the 4 towers and visit one of the 6 cranes.

My visit of the ship is not finished. During breakfast, the steward arranges an engine tour with the chief engineer, provided I don’t tell the captain, who doesn’t like when passengers go to the engine room. Just like the officers taking shifts on the bridge, engineers take shifts in the engine room. And it’s much less pleasant than on the bridge. And terribly noisier.

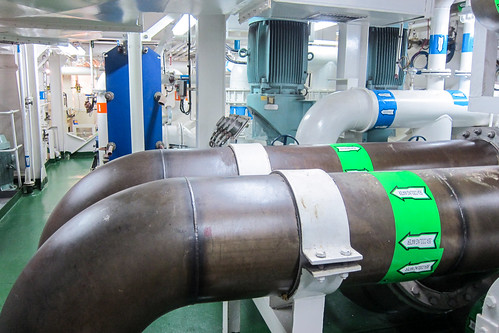

Despite being called a room, it’s a space as big as a 4-story building, which top floor is right under the “ground floor” of the living area, i.e. the poop deck. Everything inside is huge.

On the top floor, the control room is covered with screens that display the status of each piece of equipment, the volume and temperature in each tank, etc. This can be displayed on the bridge screen as well. The main engine spans over 3 floors. At the bottom level, where the propeller shaft is, we are a good 5 meters under sea level.

The chief engineer takes me downstairs without ear protection, through all the engines, and I become deaf for the rest of the day. There are 3 auxiliary engines for lights and electricity, and for when cranes or the bow thruster are operating. I am told they are Chinese, but they all read Wärtsilä and have Bosch components in it. One has problems and engineers are working on it.

The main engine, Japanese, has a power of 11 MW and makes 120 rpm at full sea speed. It has 7 pistons. On the wall, there is spare one hanging, and it’s quite a massive weapon. Above the engine is a 3T crane for maintenance.

It’s pretty big, but three times less powerful than the engine of the largest ship even built, the Seawise Giant (458 meters, as long as the Petronas Twin Towers in KL), which is introduced in this video by none other than Jeremy Clarkson.

This main engine consumes 40 tons of petrol per day. The petrol used is non refined petrol, a kind of throw-away product from the refineries, it pollutes a lot and still costs around 600 € per ton. Because it’s thick like tar, it needs to be preheated to 45°C to be pumped, and to 135°C before being injected into the engine.

The feeder petrol tank is only 50 tons, so it must be refilled every day from one of the storage tanks. In total we carry over 2000 tons of fuel. We refill only from an approved supplier tanker, as sulfur levels are controlled for environmental concerns.

There is also an incinerator for trash, desalination pumps and filters for both sanitary and cooling water. No seawater is used for cooling as it corrodes the pipes. Every day, 19 tons of fresh water are produced, but the crew only use 5 to 6 tons per day. I get explained everything, from the massive steering system for the rudder to oil filters and air compressors.

The axle shaft for the propeller is as big as a very large pizza. On the photo, it’s rotating at 120 rpm (full sea speed), giving us a speed of 17 knots.

There are workshops and all kinds of spare parts. At sea, it’s like me cycling in Africa: “bring your own spare parts and know how to repair anything”. Some general engineering drawings are framed and displayed in the corridors of the crew quarters and in the main office. Some have typos, but the structure “should” be fine …

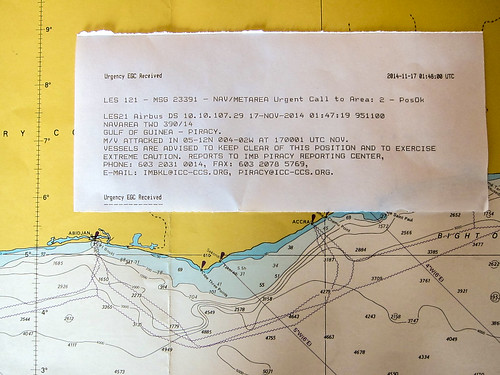

Back on the bridge, I see a note about ship attacked this morning in the HRA (high risk area). The coordinates are pointing to the city of Abidjan. We’re still far enough from the coast. There is another urgent message, telefaxed by satellite (Inmarsat): a Frenchman on a 10 meter yacht left Madeira two months ago, heading to South Africa, and he didn’t arrive. The message contains his name and description of the yacht, but no satellite phone number. It’s been a week he is expected in Cape Town, so the alerts are being distributed. I wonder if it’s possible to spot such a boat with live satellite imagery, but it seems it’s too difficult. The comment from the officer is “a 2 month trip alone in the Atlantic, and not even a satellite phone? Irresponsible“.

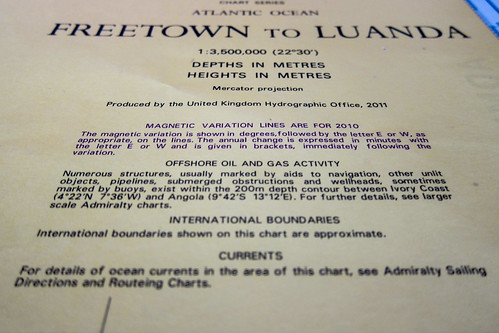

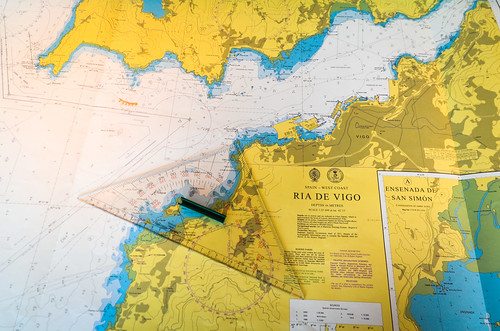

In between my video editing, which I can do very efficiently since I’m deprived of any distraction, and which reminds me of how is life in the same area but on land, I take coffee breaks on the bridge and I can stare at nautical charts for a long time. I like maps, and nautical charts are just showing me the missing part of maps. Depths, submarine cables, some offshore platforms, lighthouses, etc. Some detailed charts show the coastal towns and roads I’ve been cycling southbound. The navigation system has all kind of information: there should be nothing at sea, because it’s just water, but there are actually dangers: shipwrecks close to the coast, and abandoned wellheads on the high seas. They are pipes from former oil platforms. They are usually dismantled deep enough for boats to sail over it, but are nonetheless recorded.

Officers are compelled to work with paper maps. Even if the GPS and navigation systems do everything, they must record and forecast their position with the paper nautical charts, in case something goes wrong with the computers. It also makes a lot of paperwork. It see the officers several hours a day modifying the charts with updates that are communicated regularly. If the depth of a canal changes in a port, that makes an update.

We change time during the night, going back 1 hour. Our position is 4°S 3°W, and it’s the closest to the “origin of the Earth” I’ve ever been. I’ll remember it if that point gains any significance in the future.

Halfway through the journey, we enter the High Risk Area, the zone in red on the maritime navigation system. It’s off the coast of Liberia, and nobody seems to worry that much. The only additional rule is that we must ensure all doors that lead to a deck are locked. It’s the same procedure as when we are docked in a port, ensuring that workers or visitors cannot enter the crew quarters.

These waters are actually very unlikely to be a threat. The chief mate tells me piracy on this side of the continent is mainly Nigerian, and that West African pirates are little players compared to East African pirates. And the worst would be in South East Asia, where pirates are very organized. They would capture a cargo ship, and use it as a mother ship for speedboats, therefore being able to launch attacks far away from their base. On a world map of piracy (source), the Atlantic seems relatively spared.

His worst experience, with another company, has been in Porto Alegre (Brazil), held at gunpoint, and near Somalia, where he has been escorted on the ship by four Ukrainian soldiers/mercenaries. They had to install barbed wire on the whole perimeter of the ship. In case of attack, the soldiers knew that they had to first aim at the RPG pirate, because indeed, pirates have RPGs and they are able to make a hole in the thick steel plates of a cargo ship. By the way, there is a movie about Somali pirates based on a true story, Captain Phillips, that I found worth watching (free streaming).

Apart from piracy stories, the chief mates also tells me about his experience in sailing the Great Lakes of North America. It must make a great trip, to cross the Atlantic, and then cross a third of the USA, still on the same boat.

We experience quickly so much of the seasons at once on this boat: it’s now hot on the bridge, and the bright light of the equator makes me take the same pictures as 10 days ago, but it looks better. It was also windy in the south, and it will be super cold in Europe!

I don’t have the right to touch any of the numerous buttons of the control panel, but I can watch and the chief mate shows me how it works.

There are two displays showing data from the three radars, including one on the bow. On the screen, we can click a boat and it shows its name, cargo type, MMSI (unique ID useful for radio contact), and calculates automatically where our trajectories cross. The name of the other ship only appears if it is equipped with a universal maritime identification system, which is not always the case with small fishing boats.

The two radar systems are made by Sperry marine, a company of Northrop Grumman, the US weapon maker. Vessels have the name the owner baptised it with, like Bright Sky, which may not be fine with other languages speakers. Thus, they also have an alternate name of 6 characters spoken with the alpha bravo charlie phonetic alphabet. The central screen is a GPS with maps, but every system seems duplicated.

The rudder angle is rarely null, because due to the current, the ship is always compensating the drift.

The other passenger is bored, and says the ship is boring: nobody is cheerful, nobody talks. He is used to freighter travel and compares it with his previous experience, where Filipinos had karaokes, chat and jokes. It’s true the atmosphere here is rather studious, and I would probably be bored too if I didn’t have my laptop. But he only speaks one language, which doesn’t help, and the crew has been at sea for 3 months, without going home, and they probably look forward to finishing their contract.

We are now sailing off Sherbro Island of Sierra Leone. Exactly 200 years ago, an African American sailed at the same spot, on his way to create an African colony for free American Blacks. I spot a MSC container vessel and a bird, it didn’t happen since we left Namibia!

The afternoon is alarm test time. As passengers, we must also partake in emergency drills, and gather on the deck with our hard hat and life jacket. That’s for me the opportunity to jump into the rescue boat for a minute. Leg space is tiny.

We will soon be passing between Dakar and Cabo Verde. Not close enough to get signalthough. We’re currently off Guinea-Bissau, and something has a greater reach than phone signal: pollution.

We are 150 nautical miles away from the Bissagos Islands of Guinea-Bissau, and most of the weird things floating is algae. There is a significant amount of plastic trash too. I try to spot suspicious bags, since it is believed these islands are a platform for narcotraffickers conveniently located halfway between South America and Europe. The president himself has a stake in it, and according to the Africa Economic Development Institute, the value of illicit drug smuggling in Guinea-Bissau is almost twice the value of the country’s GDP. These islands currently look like this, but I bet they may as well look like the Canaries or Cabo Verde if tourism pays more than drugs one day.

The climate is damp, how did I cycle though that? At an average speed of 16 knots we are doing approximately 700 km per day.

On the bridge computer, the chief mate shows me the software used to calculate the load of the ship (Loadmaster). Out of the 37’443 tons of stuff we can safely carry, the weight of every container and every piece of bulk cargo is taken into consideration. The software calculates the center of gravity and the sheer forces. Obviously, the vessel is 200 m long and the steel bends under the weight of the load (it also bends with the waves).

The chief mate has to make sure the draft (vertical distance between the waterline and the bottom of the hull) is small enough to enter ports without hitting the sea floor, but big enough so that the vessel doesn’t capsize. As a rule of thumb, after loading the cargo and containers, the center of gravity must be no further than 1 m above the unloaded center of gravity. The software even calculates the ship parameters when the cranes are in operation. With all these tools, accidents like these have no reason to happen.

It could, actually. This something could even break a ship. Shipping agents are supposed to declare the weight of containers, but to save money, it happens they under-declare. That’s a big problem for the chief mate, who then forecasts the ship stability with false data. It happened to him once that a supposedly 35 ton container couldn’t be lifted by a 40 T crane. Therefore, he now makes provision for extra undeclared weight when doing his calculations.

With such vessels, it’s also possible to use water as ballast in order to increase stability. Petrol tanks are also considered as ballast, since a full or empty tank will have an effect on the vessel stability. Playing with the ballast can also lower the stern and raise the bow, thus allowing vessel to gain a meter or two of clearance while passing under a bridge.

Using water as ballast is free, but it can lead to unexpected consequences: it has been found that the Great Lakes have been colonized by zebra mussels, a specie that never existed in North America before. The reason is ships discharging in the lakes the ballast water they had pumped in Europe, and containing zebra mussels larvae.

Before ships had systems to pump water as ballast, they couldn’t sail empty. They had to carry something. Colonial ships sailing between North America and the UK, bringing, among others, tobacco and cotton, to the old continent, had nothing to take back. They would be loaded with heavy and inexpensive material, like stones. It is admitted that some of these British stones are now embedded in the landscape of US cities like Charleston, Baltimore, New York, Boston, as roads and fortifications.

One major difference between cycle touring and planning a sea route is the consideration that the Earth is a sphere. It never bothered me on land, but at sea, the shortest path is not a straight line. Nautical charts use the Mercator projection, that projects rhumb lines as straight lines, but they are not the shortest distance. The shortest distance for a ship (or for a plane) is along a great circle, which is a curve on our maps. There are also meteorological conditions to take into consideration.

The officers received a weather forecast for Rotterdam: it’s 6°C … that will be a temperature shock for me. We will arrive 2 days in advance.

Despite being now 50 NM (90 KM) from Dakar, the westernmost point of Africa, it’s too far to catch a cellphone signal. I can’t see the city lights either. We’re going north now, our direction is 0°. We must have merged with the Europe – West Africa routes of other companies, since we’re no more alone in the water. I practice cargo spotting with the binoculars, estimate the distance, and then refer to the radars to see how close I am. It seems that 15 NM is my upper limit: at that distance, I just see a tiny artifact on the horizon line, without being able to tell the color.

At night, we see further, because it’s easier to spot a light in the darkness. It still depends on the size of the ship, but 25 NM (45 KM) is reasonable for a cargo vessel like ours. When passing Tarfaya in Western Sahara, with the bicycle, I remember being able to see the lights of Fuerteventura of the Canaries, just over 100 km away.

These days, there is not too much roll, but a strong pitch. Unlike the roll, there is no indicator for the pitch angle, as it’s hardly calculable since the vessel bends on the waves. I can say the pitch is enough to see the containers forward first above horizon line, then plunging into the sea. They say it’s normal, since the sea gets rougher because the North Atlantic is not friendly. Currents and storms usually departs from the USA and reach Ireland/UK after travelling the ocean. This time, the weather forecasts these storms at a lower latitude than usual, and we might hit them in the Bay of Biscay.

There are whales! Sadly they migrate southbound, so they can’t play with the ship.

For dinner, we are served a dish that the Poles call a “breton”. And it’s exactly like a cassoulet. I wonder what happened during the translation.

Watching the sunrise every day, after my gym, in the middle of all this water, is always pretty special. It’s beautiful.

We’re at full sea speed, which is when the engine cannot stop immediately, and needs several minutes to rotate slower. It means one can’t perform any operation at full sea speed. The other full speed retaining control of the engine is called full ahead. From full ahead (11 knots instead of 17), the captain can order any change of speed of the engine.

The traffic increases, and for the first time I can squeeze two ships in the same photo. Likewise, the sea gets rougher. At one point, the wind blows at 30+ knots. The ship is being mistreated, and in the trough of a wave, if feels like if the hull is hitting something.

At the same time, my laptop drive is too corrupt. Apps won’t start and it doesn’t even recognize external devices anymore. I guess this is it. Recovery from the backup partition won’t solve anything. I have a week left on the ship, with nothing to do. I knew this would happen some day, but now I feel orphaned …

I finally get to see the Teide, the highest point of Spain. It culminates at 3718 m on Tenerife island. We sail right between Tenerife and Gran Canaria, cutting the Canarias in half. These two islands are 60 km apart. We enter the area at dusk and we clearly see the lights and the shape of the Teide, despite the cloudy sky. It’s really an impressive volcano standing on the bottom of the sea.

We catch the Spanish signal for a little while, and the whole crew is on the deck calling home, since their EU numbers allow them to make intra-EU cheap roaming calls. All my EU SIM cards must have been deactivated, while my Namibian and South African SIMs connect to the network, but without credit. Anyway … we’ll be in Vigo soon.

The nautical charts are interesting. After leaving the Gibraltar Strait on our right hand side, I notice we sail above depths ranging from 4000+m to a few hundred meters within 30 km. Just nearby is the Gorringe ridge, an underwater mountain as high as 25 m under the water surface, when the surrounding seafloor is 4000 m below sea level. This invisible mountain has been discovered as early as 1875 by the US Coast Survey. When looking at the sea bed between Portugal and Madeira, even until the Açores, I’m thinking there would be plenty of nice hiking trails if the the water disappears one day. Underwater mountains have names, like “Gettysburg seamount”, even though nobody ever walked on them. This one is 4700 m high, almost like the Mont Blanc, and almost reaches the sea surface.

The 2nd officer tells me that something scary could be linked to these steep underwater cliffs: rogue waves. If an underwater current hits a 2000 m high cliff, it can produce high waves at the surface. A rogue wave is a single wave happening in the middle of nowhere, and if the ship is not reacting immediately to pass it correctly, it can destroy or capsize the ship (which explains why they are more often referred to as sailors’ tales than in scientific research). In such cases, I guess the crew can worship marine structural engineers as much as Nature itself.

Passing the Canaries means I’m back in Europe. The sea is rough again and I have been thrown away left and right while sleeping … Not pleasant. Actually, the sea is not as rough as it has already been, but surprisingly the roll is strong. And fast, from 10° starboard to 10° post. It’s necessary to walk slanted, and I can’t put up my socks if I’m not sitting down. In the middle of the night, unable to sleep (since I sleep on my side, I’m falling on my belly and on my back every 5 seconds), I have put my blanket and pillow on the floor, perpendicular to the bed. It means the roll makes my stomach move up and down inside my body, and that’s more comfortable. I have slept well when we were away from the coast though. It’s super windy and quite cold outside. Yes indeed, Europe is close…

Having nothing to do, I try a full restore on my laptop. It shouldn’t work as the hard drive is kaput, but surprisingly, Windows boots. I was working on an external drive and doing daily backups of local data, but sadly I forgot about my Lightroom catalog. A few hours of work lost … So, I spend a good part of the day reinstalling my software. Fortunately, I have the critical install files with me, so I’m able to get a machine into a decent working state even without network. That was designed for fastinternet-less African countries, but it’s even more relevant at sea! With my “new” laptop, I’m now processing the 1000+ photos … of the same boat and the same Atlantic ocean. That was to be expected …

Two days and a half after the Canaries, we reach the rest of Spain. Just when I start to discern the coastline of the old continent, my phone catches both network signals, from Portugal and Spain, and I can’t help smiling. We made it! Of course we would have made it, nevertheless this coastline is still a happy sighting.

Like for Walvis Bay, I didn’t know we were making a stop in Vigo. The seamen want our stop to go fast and leave for Rotterdam, where our arrival is planned at 5 am in 2.5 days. But in case we have to stay in Vigo for the night, they’d much rather dock in the afternoon and have the possibility to go on shore and drink at the seamen’s club or in town (during their 6-hour free time between shifts), instead of dropping the anchor at sea in front of the port. This does not depend on us, but on the port sending us a pilot.

When we enter the Ria de Vigo, in the morning, a tug boat comes to us and drops the pilot. Pilots are port employees who come on board for the last mile(s) into a port. Unless the captain has a certification for that port, he cannot drive his vessel into it without a pilot. If the pilot is busy, or if he doesn’t work outside daytime hours, the vessels are “locked outside”, at sea. As we pass the Cíes Islands, our pilot is giving instructions to a crew member steering the wheel, under the supervision of the captain.

The officers often complain about small fishing boats, any small boat actually. The rules say that in case of a crash at sea, the biggest ship is responsible. It means that us, as a big cargo ship, must be careful about the tiny ones, like the sailboat on the photo. What makes the officers angry is that the small boats know the rule, so they won’t care about the traffic, while on the other hand, a large ship needs lots of time and space to maneuver. Apparently, it also happens that sometimes, (Chinese) fishermen on very old boats crash deliberately into bigger ships, just to get paid a new one.

Vigo, in Galicia, just above Portugal, is an historically very important port. The Santa Maria of Christopher Columbus was built in Pontevedra in 1460, the estuary next door, that sedimentation rendered improper for large-scale navigation. In 1702, the Rande battle took place right here, more precisely closer to the strait where a bridge stands today, with shallow waters unsuitable for our vessel. In short, the British attempted to capture the Spanish treasure fleet, freshly back from the Americas with precious material like silver, gold, but also spices and tobacco. The British, with Dutch friends, sailed after the Spaniards into the Ria de Vigo, 25 ships in total, but silver had already been offloaded. Nonetheless, they destroyed or captured the Spanish fleet and the 15-ship French squadron escorting them, killing 2000.

Today, Vigo has the largest fishing port in Europe and is the home port of one of the world’s largest fishing companies, Pescanova, from which I have met two officers while cycling around Lüderitz in Namibia.

Also, a Nazi submarine (the U-566) could be resting just below us, near the Cies archipelago: in 1943, among others, the U-506 and the U-523 have been sunk in the area west of Vigo.

I’ll try to get in town in Vigo and get wifi to plan a bit what’s happening to me when I’m dropped off in Rotterdam. There, unlike Vigo, the port is too big and not as friendly: it’s 30 min away from town by taxi.

I doubt I can reactivate my 2-year old Spanish SIM card. Anyway, it’s Spain, so shops are at risk of being closed from 2 to 5 pm. My South African SIM card has been already picking up the 3G network of Portugal, even 2 hours before reaching the port of Vigo. Welcome back to Europe, the cold land where internet works!

Shipping planning is still messy. Now, the new plan is about unloading everything today and leaving again this very evening. There’s a big storm in the Bay of Biscay coming soon, and it’s wiser to cross it until the Channel as soon as possible. We have to discharge 200 containers here, with port container cranes that are able to moves 25 containers per hour.

The containers carrying seafood taken in Namibia will end their route here. Apparently, Vigo has no prawn (they are only in the south of Spain), so if you head to Galicia to eat seafood, you might be eating stuff from Namibia! It’s probably not only prawns, since 90% of the hake caught and processed in Walvis Bay is exported to the Spanish markets.

No wonder why Vigo hosted the Spanish fleet in the past: the estuary is ideally shaped to offer easy protection. Almost every hill on the mountains surrounding the Ria de Vigo has a castle on top.

We “park” so smoothly I don’t feel any vibration when we hit the docks. It took around 20 minutes, between the entrance into the port with the pilot, and the moorings being tightened at our berth, but 20 incredibly smooth minutes. Towards the end, the officers don’t control the ship from the central steering wheel anymore, but from a tiny panel outside. The two gantry cranes are already “unfolding”, waiting for us and start discharging the containers.

Docking doesn’t mean we are done. We must first wait inside for customs and immigration. Finally, we are told that they are not coming, so I can simply walk out. The only people showing up are our port agents, signing for the delivery of the containers.

Within a few minutes, I am walking in Vigo town center. As a man coming straight from Africa, with an Ortlieb pannier strapped around the chest, no ID, I didn’t see any checkpoint, and I was not asked a single question. I could have been easily importing elephant tusks, drugs, or simply myself. It’s strange, knowing that the same country, on the southern coast, has a high-tech system dispatching police response seconds after a speedboat is leaving the Moroccan coast with migrants.

I’m now walking again the soil of europe, two years after leaving it. And it’s so nice to see an old city center, buildings and paved lanes with history, nice shops on streets and not only in malls, and especially people walking between places and not systematically taking a car. It was not really the case in South Africa. The city is built on the edges of the estuary, and has plenty of staircases and large sidewalks, while motorized traffic must move on small lanes. It’s so pleasant to be again in a city where pedestrians have rights, where the size of your car doesn’t dictate the respect you are granted.

My main goal is to get wifi and download maps for Rotterdam, as I’ll disembark probably on a Sunday in an industrial area. The appalling absence of unsecured networks in town pushes me to walk into a bar with wifi, and to order an almond croissant, interesting side effect. And since I’m missing dinner time on board, I buy a kebab. It’s my first kebab in two years! Yum! Hmmm … It’s like MacDonald’s actually, food with very short positive feelings.

On the way, I also grab a bottle of albariño, chorizo and Belgium beers. They are sold for 1 € in supermarkets … I used to think that African lagers are bad, but at least cheap. Now, they are just bad. I must have been overestimating Cape Town, which does look good after Congo and Angola, but is maybe in the end just overpriced. I run back to the ship for 20:00, as containers are supposed to be discharged by 21:00. Since shipping times are loose, I take no risk. The crew told me they have no record of missing passengers, but I also know they are working for the cargo, not for passengers. Passengers are indeed paying to be on the ship, but they have little freedom and little rights. Therefore I wouldn’t want to be late when the ship leaves, I don’t think they would wait for me.

Many women are walking alone in shady areas at night, like the underground parking close to the port. And it’s safe! Re-entering the port without an ID is as easy as leaving it. There are no checkpoints, just an intercom at an automated gate. I just have to say “I’m going to the Bright Sky” and that’s it, it’s open. I’m then walking on the port with bulk cargo, heavy machinery equipment, small crates, etc. If I was a manufacturer, I wouldn’t want it to be left like this in the open. I understand docked vessels have their own security day and night to check who is coming on board.

But what’s that on the vessel? There are too many containers left on deck, while I thought we were discharging most of it. Then, I learn that the 65T crane is “broken”. The crew doesn’t know yet if we’re staying docked all night long, meaning a drink outing in Vigo is possible, or not. And 10 min later, the crane is working again. Now our new estimate for departure is 1.30 am. It really sounds like merchant navy is not for people who like tight plans!

Leave a Reply