These three posts are not about cycling, but about my experience as a passenger on a cargo ship, back to Europe from Cape Town. There are not many reports about it on the internet, so I decided to post mine.

Before leaving on the cycling trip, I had that vague plan of (maybe) reaching South Africa, find a job in Cape Town, and see what happens. However, during my trip, South African immigration laws have been tightened, and that plan is no longer possible. Changing the visa status is now impossible, overstaying is punished and even extending a tourist visa has become complicated, so my only option was to leave (or to cycle back via East Africa, but I was not so motivated …)

After taking 1 year and 10 months to cycle all the way down from Zürich, I didn’t want to “just fly back”. I was not ready to grant a twelve hour long journey in a flying sardine the right to close my cycling chapter. I thought that finding a cargo or a container ship was my best option: they take three weeks to return to Europe, they don’t fly too fast, and they sound like a much nicer experience. So I thought I’d just hitchhike a boat on the port of Cape Town, and offer to help in exchange for the passage. However, it’s far from being that easy.

First, there’s only a few shipping lines connecting South Africa with the rest of the world (map source), compared to what is happening in the northern hemisphere: the several connections between Europe and Africa mainly call at West African ports and don’t sail further south than Nigeria. The most sailed route seems to be Europe-Asia, where vessels use the Suez canal and leave South Africa more or less abandoned at the bottom of the continent. Only a few Brazil-Asia routes would stop in South Africa, but it’s not where I am going. Thus, I am left with the few companies serving especially South African ports, Maersk and MSC, and who barely sail once a month. There is also Safmarine and MACS, a small German shipping company dedicated to the Southern Africa – Europe route, and which actually enjoys a monopoly on cargo freight. If they are any other solutions, they don’t have a schedule or are not big enough for the internet.

Then, hitchhiking at a commercial port is very unlikely to happen. Security makes it impossible to access the wharf. Yves told me he managed to do that between the islands of the Indian ocean, but that was with much smaller ports, and especially, that was 20 years ago. There is also a website where private boat owners (yachts, sailboats) recruit staff, but they expect money and sailing experience.

I tried to call every shipping company in Cape Town, but they only deal with cargo and containers, while potential passengers would have to call the headquarters. I then called Europe, just to be told that they don’t take passengers anymore, or for the few that do take passengers, that it’s done via agents. There are indeed agents specialized in freight travel: they are small companies in Germany or in the UK that are given the rights to sell the empty cabins of commercial vessels. And it’s roughly 100 € per day at sea.

In the end, the only freighter travel agent that has ships on a route from South Africa tells me it’s fully booked until the end of the year, except for one cabin. Freighter travel is becoming trendy, and with only 2 passenger cabins on the ships sailing from Cape Town, there’s basically no way I can get in for free. I end up paying my passage, from Cape Town to Rotterdam, like a tourist. It’s a lot of money, three times costlier than a flight, for 22 days at sea. I could easily cycle for 6 months in Africa with that money. On the other hand, it’s an interesting experience that requires lots of time at once, so if I don’t do it now, I don’t when will the next opportunity be. The agent charges a fixed price per cabin, which includes food, plus various insurances. So in the end, it’s more like booking a hotel with full board rather than booking a flight.

Ironically, a few days after booking my passage, the man behind me in a bar in Cape Town happened to be a former MSC employee. He said there is maybe a way to get a cargo passage without paying, but it would involve good connections and require the traveler to be super flexible on dates. I also met a Chinese cyclist (who cycled all the way from China) who tried to get a free passage back to China, on Chinese ships (i.e. without the “annoying” western regulations about safety and comfort), but without success.

With the confidence that I didn’t pay for a service I could have gotten for free, I wait for my ship in Cape Town. Since I will be fed, I won’t have to work, and I will be cut from internet for three weeks, it’s the perfect time to focus on editing my cycling movies, a task I couldn’t cope with on the road. Roughly speaking, it takes me a full day to compile a 10 min video.

It was first scheduled on October 30th, then on November 7th, and it’s finally today, on the 9th, that I am notified that I am boarding. The communication was bad and it was unclear until yesterday. Delays are expected, and the travel agency clearly advises travelers to have accommodation sorted out for a few days before and after the planned day of departure. My ticket actually reads “departure date approx. end of October/beg.of Nov 2014“.

Eventually, I’m departing with a delay of 10 days, which makes me leave South Africa just 5 days before the expiration of my tourist visa: involuntarily awesome timing. My boarding is not organized by the freighter travel agency, nor by the shipping company. It’s a third party, the cargo agent, who is supposed to make sure I am on board. The cargo agent is the local contact of the shipping company that is in charge of the goods during loading and unloading, and all the paperwork that goes along.

The appointment is fixed with Zolisa, from the cargo agent company, the inside the port, that I can now enter with my ticket. I show up at the northern gate of the port of Cape Town, in Paarden Eiland. I have not cycled for 2 months and am well out of my “cycling mode”, and I forgot to re-attach the bottom hooks of my panniers that I had removed to use them as quasi-normal luggage. My ticket would let me pass through the port gate if the fat security lady didn’t say that “cycling is forbidden in here“. It’s because it’s an industrial area, so safety first. But she says walking is allowed. Fine, then, I’m just gonna walk and push my bike for a kilometer.

But then, the usual stupid security dialogue happens. “No, you can’t go with your bicycle.” What if I carry it on my shoulder, I’m a pedestrian with a luggage, right? No way, the lady decided she won’t allow my wheels to pass the gate. “You have to put it in a car” is her final answer.

So I have to call the cargo agent and ask them to fetch me. Zolisa comes to me, but his car is a small city model. I can make my panniers fit and half of the bike only. I have to deflate and remove the front wheel, which is annoying me even more than arguing with a stubborn security officer. Because we are kind of blocking the entrance and I am losing screws on the floor, the officer finally renounces to make me pack the bike inside a car, and I can cycle Duncan road “as long as I follow the car and I don’t injure myself, or anyone else”. Fine, I can do that.

We visit the port immigration office, where the officer makes me notice that my passport picture looks like Sébastien Chabal. Eh yes, I made it when I was in Windhoek, and South Africa may be one of the few countries where rugby players are more popular than Zidane. I get stamped out, but then we have another problem to reach the wharf: there is a second security gate, where PPE is compulsory and where it’s very unlikely they let me cycle in. Zolisa has to call a friend with a bakkie, just so that we can drive the 200 m distance between the immigration office and the ship without being bothered. It’s Sunday and the port is completely deserted. I didn’t think two wheels would cause that many problems … but finally, I am on the wharf!

I carry my bike and panniers on my shoulder, via the rather steep gangway, but I’m used to staircases. I meet the captain and the chief mate, get to my cabin to drop my luggage, and take the bike “downstairs” in a small room close to the gym. Pfiou, finally! I’m sorted out for the next three weeks.

The captain keeps my passport but Zolisa takes me back in town until the boat departure, in the afternoon. It was a problem getting in with a bike, but now, even without a passport, it seems I have no problem getting in and out of South Africa.

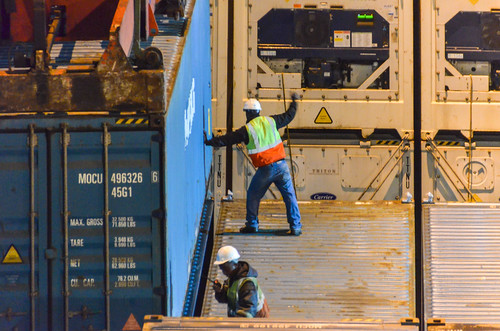

Back on the wharf, I take many pictures of the mobile harbour crane. It’s a Liebherr LHM 550 with 144 T lifting capacity and 80 tires, fun to watch in operation. It’s apparently forbidden to take pictures on the wharf, but no one stops me. The very few port staff are all chatting in the shade of a building a bit further.

We quit the port of Cape Town at 1500. The tug boat, attached to us with a rope, guides us until after the container terminal. From the top deck, which is five floors above the poop deck, which is itself about 5 meters above the water line, I seem to see everything in the city, and compete on a fair ground with tall buildings like the Customs House and the Civic Centre.

As soon as we pass the last dike, the wind starts blowing terribly. Cape town, Table Mountain and later the 12 apostles become more and more visible, it’s very pretty. Seals and dolphins jump in the water around the boat. I feel the rolling stronger and stronger too.

The sky is blue and bright, just like our vessel, called M/V Bright Sky. From the bridge (top deck), Table Mountain withdraws itself from sight for the next two hours. We pass west of Robben Island, and we will sail along the African coast until Walvis Bay, a Namibian port on the programme, and then head straight to West Africa, thus avoiding the dangerous waters near Nigeria.

When we are distanced enough, there seem to be only one white cloud in the sky, sitting right on top of Table Mountain. So maybe if the Cape was flat, the weather would be much nicer?

It’s not my first time on a cargo ship. When I did my internship in a shipyard in Japan, we went for a sea trial around the Goto islands in the East China sea. I had less time for taking pictures, since we were testing the engine and measuring vibrations of the hull. And we were sleeping on our own mattresses on the floor of empty cabins.

On this ship, there are two passengers cabins to chose from, Ingenieur version and Owner version. I could only book the fancy one, so I end up with two single beds and a mini lounge. It’s not like in a cruise ship, but it looks very comfortable for what I expected. I’m on the D deck, just under the bridge, and windows have an open view forward, so it’s a good seat if we happen to crash into a cliff.

There is a TV into which I can plug my USB drive, a fridge, coffee and a kettle. The bathroom is slightly smaller than the unit bath I had in Japan, it’s a shower-toilet-sink all-in-one molded in the same sheet of plastic. Everything must be tightened or locked, like drawers, else they would open with the rolling.

The vessel itself is a great piece of engineering. It’s a multipurpose vessel, meaning it’s designed to embark both bulk and containers, and it has its own cranes to unload its cargo by itself.

With a length of 200 m and a breadth of 30 m, it’s only half the dimensions of the largest vessels, such as the Maersk Triple E class or the latest CMA-CGM Kerguelen (video). I can’t imagine how gigantic these two are, since the ship I am on right now is already impressive. Its container capacity is 2208 TEU, 8 times less than the two container vessels, but it’s much more functional: it has 5 cargo holds and a tweendeck, meaning that under the containers, it can carry 15 different types of bulk or break bulk, and even more with adjustable walls. Between the hatches, it has 6 cranes of 120 T, lifting up to 240 tons when combined. It’s like the Swiss army knife of commercial vessels!

My German resurfaces little by little as I speak with the other passenger, a retired German man who can only speak German. Since this kind of trip requires time and money, I guess retired Western people make most of the customer base. It’s like a cruise ship, without the comfort and the socialization. Yes, it’s a special kind of travel …

At the exception of one officer, the crew is Polish and doesn’t speak German. The language with passengers is English, as the officers and the steward can speak it. There are 21 people and 3 cadets (apprentices). With the two passengers, that makes 26 of us onboard.

I still have signal while we are 25-30km offshore. It means cellphone reception is better at sea than in some parts of Cape Town! After sunset, I can spot a lighthouse in Saldanha and the lights of the shore.

At the end of the half-day, spent standing, my feet hurt from constantly counter balancing the rolling effect. What is great is that I have access to the bridge, just above my cabin, so I can always walk up and watch maps and radars. It’s however forbidden for passengers to leave the stern where the building is, and venture on the cargo area or to the bow.

I am so tired that I fall asleep without any problem. I tried to connect the TV and the stereo without success, so I can’t have a mini home cinema in my cabin lounge.

I can’t say I had a first good night though. I woke up too early and couldn’t fall asleep again, since my body was being moved left and right with the roll of the ship. I was hitting the pillow with my nose, and five seconds later, with my neck. And yet, my cabin is pretty central, so it must be hard for the crew sleeping away from the roll axis. I should sleep in a hammock.

Today’s bad news is surely my laptop agonizing. Windows often shows hard disk errors (corrupt sectors and unrepairable) and the restore partition often boots because the main partition cannot start. I hope I can make it survive for the whole trip so that I can compile my videos. Without laptop, the whole passage will also be boring …

Today’s bad news is actually a worse one: I decided to take a photo inside the cabin with the tripod. My gorillapod is well aged now and the knuckles are getting loose. It’s always drooping a little. It was not a good idea to place it on the desk, … plus, the rolling doesn’t help. My camera fell on the floor, and the lens broke open.

The lens motor cables, the circuit and some screws are broken. There’s no way I can mount it back, not even in manual focus mode. It’s a disaster … It had fallen before, in the nature, but luckily survived until today. Well, now, everything I have is somehow broken: laptop disk, main tent pole, camera lens, bike frame braze-on, phone batteries, shirts, etc. I still have a P&S camera, but it’s a shame I won’t get good pictures of the ship and the sea.

I use that lesson to secure my laptop on the table. All desks and cupboards of the ship are covered with a rubber lining sheet that sticks to surfaces and objects, but adding a bungee cord won’t hurt.

Meals are served at the same time every day, 730-800, 1145-1215, and 1730-1800, in the officer’s mess on the poop deck. We have a dedicated seat. We (the two passengers) sit at the table with the captain, the chief mate and the chief engineer. The second and third officer, with the second engineers, sit at the other table. The rest of the crew eats in another mess on the other side of the kitchen. The crew includes one cook and one steward, who is also the person of contact for passengers. The kitchen is always open with a fridge full of food, in case we are hungry at other hours.

During the day, while chatting with the second officer, I learn that this ship was custom built. If it has 6 cranes, it’s because it was necessary for the shipping company. The ship doesn’t call only at major ports, but also at smaller terminals that don’t even have a crane. For example, in South Africa, it stopped in Cape Town, Durban, Richards Bay, Port Elizabeth, and Ngqura. On its own, it unloaded a Siemens transformer of 217 tons by joining two cranes.

Early 2015, this very same vessel has also delivered new Vossloh locomotives for Prasa in the port of Cape Town (news article). It doesn’t sound very different from the colonial times: technology sails from Europe to Africa, while precious metals and minerals are sent back with the same ships.

The vessel was build in China but is registered in Majuro, in the Marshall Islands, a country of 60’000 people halfway between Australia and Hawaii. Talking about registration in countries were corruption helps, I am told that the first man who opened a registration office in Liberia, paid 1 million dollar to the government, but became billionaire the first year. Today, the Liberian Registry (headquarted in the USA) is the second largest in the world and includes over 3900 ships, which is over 10% of the world’s oceangoing fleet. The Marshall Islands host the 3rd largest registry, a list topped by Panama. Flags of convenience are heavily used to avoid taxes, trade unions, environmental regulations, etc.

Sea seems to be less regulated than land anyway. The third officer has a story about pipes being shipped from Durban to Rotterdam, and then back to Durban without any transformation. Apparently freight shipping can be cheaper than paying taxes.

We also talk about stowaways, which is something to consider on a vessel commuting between Europe and Africa. Even if South Africans are not expected to hide in a ship like, say, West Africans (who are, by the way, far less likely to obtain a visa for the EU as easily), it does happen. The vessel hires a security company to watch the boat while docked in a port. There are many locals working on the ship who are not part of the crew, but who just come to load and unload cargo. If they are not registered carefully, or if all the doors are not locked properly, they could easily hide in the ship. For such a big structure, the 2nd officer tells me he knows places where he could hide for more than 3 hours without being discovered, even if a whole police squadron were looking for him.

When a stowaway is discovered while at sea, by law, the crew must feed, accommodate and protect him. It can already sound like a victory for him, but there is another trick: some European ports will refuse a vessel to dock if a stowaway is known to be on board. So if it’s still possible, and depending on the cost that the shipping company would incur, the vessel would stop in an African port and disembark the stowaway.

There is a story about one of them: a Mozambican had traveled by land from Maputo until Durban, to embark illegally on a ship for Europe. Durban is apparently a tricky port for shipping companies, and an opportunity for migrants, because not all workers wear uniforms. The guy jumped on a boat and hid … only to realize later that he boarded the vessel that only commutes between Durban and Maputo. So the lesson before hiding on a cargo ship is to check that the passage is a direct one to the wanted destination. Websites of shipping companies would have this information.

The vessel has a mini duty-free shop onboard. It’s on the D deck, like my cabin. Every 2-3 days, the captain makes an announcement at the radio, in Polish, something like “the shop is open now“, and the crew queues in the corridor to buy vodka (Smirnoff at 6€) and cigarettes (Marlboro carton at 14€).

There is no phone signal today. We sail approximately 50 NM (90 km) from the shore, instead of 25 km yesterday, so it’s too far to catch network of Alexander Bay or Oranjemund. The only network available then is satellite phone, but it’s only for emergency as it’s too expensive. Crew members have access to an email address (text only) that the shipping company let them use for free. As a passenger, I can request the use of internet or phone, but it’s at satellite prices! Crew members can’t make cheap calls either.

For dinner, guess what’s on the menu again? Potatoes. I’ve never been to Poland, but something lets me think that Poles can cook potatoes in a hundred different ways. I had them fried and boiled, and this time, it’s as a pancake in a goulash. It’s the fourth time I’m eating potatoes within less than 2 days sailing. Even breakfast has potatoes! For lunch, I was asked “side dish, rice or potato?“, and answering “rice” has never been that obvious.

Our average speed over land (different from speed through water) is 11.5 knots (21 km/h). It’s just like me cycling! The moon was full two nights ago and it’s still very bright. At night, we don’t need light at all to see the deck and the sea.

My second night is bad again. I had a water bottle close to my bed that I didn’t secure properly, and it rolled all over the cabin until I got up. In the morning, without enough sleep, but just the bare minimum to call it a night, the ship roll prevents me to fall asleep again.

I’m not sea sick, it’s just that I’m not used to my bed being constantly shaken! I’ve had the most peaceful nights in the desert in Namibia, which is just 100 km away now, but the sleeping at sea is trickier than finding the perfect hidden spot to set up my tent. This website suggests tricks that I ignored at the time:

- Hammock – A hammock strung fore-to-aft will let you lay motionless while the ship rolls beneath you. It won’t remove all motion (you still feel the up and down heave of the ship) but it does reduce the rolls.

- Be A Burrito – If the hammock doesn’t work for you try wedging lifejackets under your bed to create an acute angle between the mattress and the wall, then climb in. This essentially turns your matteress into a burrito shaped shell, pinning you against the wall and preventing you from rolling in your bed.

The 2nd officer makes me notice that all cabins have a sofa, which is generally placed in a different direction than the bed. That way, depending on which is the most annoying, pitch or roll, one can choose the best sleeping surface.

Because I can’t sleep, I decide to go to the gym before breakfast. The morning sun clearing up the ambient mist is wonderful, but the gym is at the lowest floor, just under the ship office and just above the machine room. It has a few gym equipment, including a broken swimming pool. The ship was built in 2013 and the pool is already “broken”, but that’s a Chinese ship. Because it’s the first year of operation, the crew is still looking ll around the vessel for defects.

Within 30 min, I burn 1000 kJ while cycling and “running” on the elliptical trainer (equivalent to the energy contained in 100 g of jam or chili sauce). I have to hold tight on the handles because the ship movement make it quite unstable. I wonder how it is to play ping-pong on the waves.

It means that while cycle touring, I must have been easily burning between 10’000 and 20’000 kJ per day? No wonder why I could eat like Dwayne Johnson without gaining weight. Apparently the body is used to absorb a lot and burn a lot, but after such a regular effort, it takes some time to readapt to a “normal” lifestyle with a “normal” food intake.

After breakfast (with camembert instead of potatoes!), I get to the bridge to have a look at the quiet sea. There are some seals around us, but compared to yesterday … it feels like in Pirates of the Carribean! The sky on the left is perfectly clear. But on the right, the mist is swallowing us, and the front crane, a mere 150m ahead of the bridge, is hard to discern. I check on the map, and, obviously, we’re right next to Lüderitz (100km offshore), the remote town in the Sperrgebiet that already gave me a taste of its unpredictable and rough weather.

It’s great that I experience now the “other side” of the Skeleton coast (in its definition extended to the whole Namibian coast). The wind was terrible on the land, and the desert was populated by shipwrecks and stories of sailors stranded there. It’s logical after all, if the desert mist extends as far as 100 km into the ocean. The cause is the wind blowing from the hot desert into the cold Benguela current. Portuguese sailors once referred to it as “The Gates of Hell”. It doesn’t happen on the Saharan coast, for example.

I complete my first video, West Africa 1, and I sew the hole in my favorite (only) pants during the compression. In the meantime, dolphins and seals play around the boat. Seals sometimes jump out of water, and sometimes impersonate laziness, when they group-drift on their back with fins out of the water.

Two days and a half after departure, we stop in Walvis Bay, the export gate of Namibia. Even with our slow speed around 20 km/h, that’s a fair time, considering it would take 1600 km by road. The engine running 24 h helps.

The 2nd officer explains to me how maritime charts work and access channels into ports. Our vessel, fully loaded, has a 11.7 m draft. Naturally, ports must be at least that deep. In Durban, they sometimes have to wait for the high tide to leave the port. He also explains how the containers are tied to the boat, as I’ve always wondered how can container vessels carry such high columns of containers that never fall despite the roll (oh, it seems they do). Our bulk carrier can only carry 2208 TEU (20-foot equivalent unit), while a ship of the same size without the 4 crane pillars could carry more than 3000. Container-only ships that can be loaded with 8 times this amount of containers end up with a much more affordable pricing. That’s why we mainly have cargo and bulk, i.e. heavy stuff cumbersome to carry. We will get even more of this, because we stop at the port of Walvis Bay to load huge blocks of granite.

When I did the booking, I didn’t know if we would stop somewhere on the way. I wake up while we are docking in Walvis Bay for 24 hours. My old MTC SIM card with 70 MB of remaining data is still working fine. We are allowed to get off the ship and use a copy of the passenger list to visit the town, instead of our passport, which stays with the captain, alongside with the passports of the whole crew. With the other passenger, I am leaving the ship for the city,

Walvis Bay is the British city of Namibia. It was transferred to the Cape Colony, and then to South Africa, thus remaining an enclave while the Germans took possession of South-West Africa. When Namibia gained independence, Walvis Bay remained South African for 3 more years, until the end of the apartheid. It’s the only place on the rough Namibian coast with a natural harbor, so no wonder why it’s economically strategic. It’s one of the three Namibian cities of the top 10 largest cities (a population of 20’000 only is needed to enter the list) that I didn’t visit it while cycling, since I turned off in Swakopmund, just 30 km north. Even if I didn’t like the weird-German-Disneyland character of Swakopmund, and the painful headwind that hit me both times when entering and leaving the city, at least it had a character. Walvis Bay is the same kind of city, lost in the desert, but despite being called the economic lung of Namibia, seems much less livable. I don’t regret not to have cycled through it.

When I was cycling and approaching a large city, I didn’t have the notions of “rest” and “decent food” on the top of my mind. Instead, I had the pressure of finding everything I needed, often a preventive spare part. Here in Walvis Bay, I am in the same situation: my priority is not to visit the city, but to repair my broken lens or to find another one. I have a day for this task.

The only photography shop has a German name, but they don’t do repairs, they don’t sell Nikon lenses either. The owner calls a colleague in Swakopmund, 30 km away, and I am told a Nikkor 18-55 is available for N$2500. It’s the exact same lens I broke, but at twice the retail price. I decline the offer.

Walvis Bay is the second most populated city of Namibia, but it really looks like a single street Far West small town, with all businesses on that same street. Further down, there is a small electronics shop, and I hope they are the kind of people who unlock phones and repair everything. Unfortunately, they say the only way to assemble a dSLR lens is with a bench that only Nikon technical centers have. But they do sell a few lenses … and what do I see there? A Tamron 18-270 with a Nikon mount. It’s the exact lens I wanted to upgrade with! I’m forced to invest now. I should have bought it in South Africa, where it was 15% cheaper. It’s the usual markup, since most of things in Namibia come from South Africa.

A new lens is much better than no lens at all, and finding the lens I wanted in Walvis Bay was not expected, so I can’t miss that miraculous opportunity. And maybe I can also claim the VAT (15%) back? We walk to the port customs office, aiming at getting N$762 back in cash. I am led from office to office, as expected, until the right lady tells me about the procedure: I can’t get the cash back, but a customs agent will come on board and check the goods before stamping a form, and then the money will be transferred to my account. Really?

Well, it’s 12 and I did everything I needed to do. My mission is over, and we can now relax. With the other passenger who only speaks German, we head to the tiny waterfront and try all the places.

There is a restaurant managed by a French man with a tee-shirt of the Delirium Tremens (but that beer is not sold here), and whose chef has been voted best chef of Namibia for the past four years. The customer at the neighboring table tells us oysters here are the best in Africa, so at 1€ per piece, I’m going for it. That other customer is the French consul for the region, and of course he knows the ambassador who renewed my passport in Windhoek. While cycling in Namibia, I kept saying that everybody in the country is related or connected. And a 24-hour stopover re-validates it! Forty years ago, the consul drove from France to Abidjan in a Renault 4, when roads didn’t exist yet. Which goes to show that crossing Africa can lead to a decent job …

Late afternoon, it winds up and Namibia appears as I know it: rough. Sand is blowing into my eyes, it’s hard to walk against the wind, and my face feels red from the sun. We return to the port, where none of the security people ask us for anything. We could have been local guys carrying a bomb straight into the boat, as we had no ID and didn’t go into any security check at all. In South Africa it wouldn’t have been possible, I guess even less in Europe, but Namibia is too relaxed. I like Namibia for that, people have a relatively good life and are too relaxed to complain, to annoy tourists and to ask for a bribe-present.

Relaxed doesn’t mean useless: a lady from the customs comes on board with a tax return for new lens. She came all the way just for me. Despite having spent the whole afternoon in all the bars of the waterfront, we fill the required papers, she takes me to the port entrance to get the stamp, and drives me back. It seems like a well defined process, I’m happily surprised. I’ve been too accustomed to the “I want to see money in my hand right now” thinking, when nobody trust each other. Lack of trust in people and public institutions seriously hinders development and implementation of optimized processes. Here, things work, Namibian presidents are praised for their sense of democracy, and I even feel likely to find N$760 on my account within the next 3 months (note: I’ve been too optimistic. Six months later, Namibia didn’t send the money).

The ship officers tell me that the granite blocks couldn’t be loaded today, so we can’t leave tonight. We’ll leave tomorrow afternoon instead. Good, then I can return to town to buy shampoo and toothpaste.

The next day at 9 am, the port cranes are standing still. I thought they were supposed to quickly catch up with the work from yesterday. The port agent had said they’d load the granite from 7 am, but the workers didn’t show up. It’s their first time loading granite blocks and they don’t want to do it at night. The captain keeps repeating “this is Africa” as nothing happens as planned.

I hadn’t heard these words so much lately. Actually, not since working on that power plant project near Johannesburg. During my trip, I’ve not heard, not felt like saying the TIA thing. I realized it mostly happens when Westerners are in Africa, when they are accountable for work done in Africa (often with poor quality and delays) and must report to hierarchy elsewhere (usually with high expectations and little understanding of the different business environment). When things are done entirely within Africa, there’s no need to be “this is Africa“-ing everything. But when you expect the port agent of Walvis Bay to work as quickly as the port agent in Rotterdam or Hamburg, you can only be disappointed.

Now, we are told we will leave at midnight. So that’s another unexpected full day in Walvis Bay! I didn’t know maritime shipping was so random and relatively unconcerned about delays. The reason why the vessel arrived 10 days behind schedule in Cape Town? There was a “traffic jam” in the port of Durban, and the crew had to wait for 5 days anchored in front of the port.

Despite being docked, I feel the ground is moving in my cabin. Am I going crazy? Is my brain so accustomed to the ship roll that I’m permanently auto-balancing now? I check various angles and alignment marks by the window, and … we’re perfectly still. Yet my body feels some movement. On land yesterday, it didn’t happen.

The second officer tells me it’s normal. We always have one or two auxiliary engines switched on (for lights, drinking water, and especially for operating the cranes), and the ship is indeed moving. So slightly that we can’t see it, but enough to feel it.

Since we are docked and one hatch is opened, the 2nd officer gives me a tour during his break, as it’s probably my only chance to see “inside” the vessel. It’s very deep … and being a tweendeck, I only see halfway down! There are already 3 of the 16 granite blocks (but they look pretty white for granite) and a few containers. It’s so much steel and so many functions, a real big toy. Under the tweendeck, in the cargo hold, we have manganese, and other stuff from South African mines.

I am also shown how containers are stacked and tied together. The bottom rows of containers are tied to the deck with twistlocks and lashing bars. The containers above are attached to the containers below with twistlocks. There are manual ones, semi-automatic and automatic twistlocks, that lock and unlock automatically with the weight of the containers when they are being laid or removed by a crane.

Since we have the whole day docked, and since I didn’t cycle around Walvis Bay on my way down, it’s my chance to visit the salt works. The town is built near a lagoon, and there’s probably more to see than very quiet main street and the tiny waterfront.

We walk out of the port and book a taxi for two hours, so as to drive in the salt works on the southern side of the lagoon.

Colors are stunning. The loneliness and grandiosity of the desert is already attained with a 5 minute drive out of Walvis Bay. I really enjoyed cycling in Namibia and I still like it now. This unexpected escape into Namibia, without passport, feels very good.

Here is produced more than 90% of the salt used in South Africa. With a production of 700’000 tons per year (from the processing of 50 million tons of seawater) over an area of 4500 ha, the salt pan is the largest producer of solar sea salt in sub-Saharan Africa.

The pan is big, red, with plenty of pipes and birds, flamingos, and of course lots of sand. It’s the Namib desert after all. The wind is strong, and my hair is stiff from the salt and sand being blown in it.

The taxi drops us at the waterfront to spend the rest of the afternoon. The city is empty. First, it’s not as touristy as Swakopmund, and second, November is the last month of the tourist season. After that, it’s too hot. I barely see a tourist in town. To tell the truth, I barely see anyone.

Once back to the ship, early enough to make sure it doesn’t leave without us, the 2nd officer confirms that the white granite blocks, that caused so much problems, are indeed marble blocks. Each block, roughly the size of a Citi Golf, weighs 15-20 tons. It costs around 500 € to transport one block from Walvis Bay to Hamburg, loading and offloading included. With the price difference between Namibia and Germany, it’s an easy way to make money with Africa’s resources!

I also ask about the possibility of working on a ship and having the passage for free, like people did years ago. I am told that since 2001, cargo ships can’t take passengers for free against a small job. Even deckhands must have a certificate. Also, ship captains are no longer allowed to hire who they want, the paperwork is handled by the company headquarters. It’s a confirmation that freighter work and travel is much more regulated than before, and that I could have waited for days at the port. However, it should still be possible to board and work at ships like the Greenpeace fleet, on private leisure boats, and probably on Chinese fishing vessels who don’t respect any rule.

On this vessel, the two passenger cabins are constantly booked. Officers are allowed to take a relative with them, but only if a passenger cabin is free, which has never happened.

At night from my cabin, I watch the last containers being loaded, while the captain makes an announcement for departure: it will be twenty-two hundred. I keep trying my new 18-270 lens, now at night, and I like it. It’s a superzoom but quite light and fits in my small bag, being just as long as the Nikkor 18-55. It’s perfect for travelling, I should have bought it for my cycling trip!

I have now made 3 trips to Namibia and love the place. I found your descriptions to be fascinating and deeply personal. Superb writing. I am trying to find an available cabin in a ship from Walvis Bay to Cape Town but so far have had no luck. The only things I found seem to be for super rich and uninteresting people from OECD countries.

Definitely not for me.

Any advice?

Hi Steve, thanks for your message!

Sorry I can’t help there, it’s been a while. I’ve heard that some cargo passages have not reopened to passengers since covid, so it may be harder today indeed. Have you managed to talk to skippers with sailboats in the Walvis Bay marina? Depending on the winds it may be possible to buy or work your way to CT.

Great adventures!

Great adventures !Love them

Great post – I am taking trip on same ship in November from Antwerp to Durban. Looking forward to more info from you on all aspects of the ship and trip. Have been to all the places ship docks and have spent many years travelling in southern Africa so looking forward to seeing them from the seaside.

Cheers

Thanks! Two more posts coming up soon, but doesn’t it kind of spoil your future trip? 🙂

Hi – not at all, hearing your perspective on the voyage actually adds to the enjoyment and anticipation of my pending trip -and you have some great tips. Have been travelling the world all my life but Africa keeps pulling me back – your photos are really good and bring back wonderful memories.

Regards