Going back from Lüderitz, up to Aus, on that same an unique B4 road, I will this time stop often. Anyway, this time, the 120 km stretch with the gradient and wind won’t be possible in a day.

There are several abandoned train stations along the Aus-Lüderitz railway and I will peek in, and hopefully spend the night in one of them. There’s no other shelter anyway, and being in the Sperrgebiet, it’s forbidden to leave the road. I could try just to test if there is a kind of “Sperrgebiet armed response” in place, but most importantly, the mountains are so far away from the road that it’d be too annoying for me to try to hide in the desert.

Talking about the railway, which is undergoing renovation works, there are new sections right at the exit of Lüderitz already. I was told many times that the renovation project collapsed due to missing funds, but it seems alright now. Maybe thanks to the ubiquitous savior of Africa, the Chinese, with (afaik) two contractors on that railway.

It reminds me that I heard that the Chinese were already 100’000 in Namibia, and if true, they would quietly make up 5% of the whole population. The latest figures from 2006 quote 40’000. I also learnt that the reason of the railway renovation stands 300 km away from Lüderitz, at the Scorpion and Rosh Pinah mines. The mines currently transport their mineral (zinc, and some copper, tin, lead, and silver) by truck to Lüderitz, and some of these trucks are driving very disrespectfully towards bicycle(s).

Considered the remoteness and the attractiveness of Lüderitz, I understand a railway wouldn’t be profitable without the industry. It also makes sense that the port of Lüderitz undergoes an upgrade.

Enough about the railway for now, my first destination of the day is the ghost town of Kolmanskop.

The ghost town is closing visits at 1 pm, so I can’t have a lazy morning if I want to attend the guided tour at 11. Kolmanskop is facing Lüderitz airport, 10 km out of town.

I already wrote about the Sperrgebiet, the restricted diamond area, on my way to and around Lüderitz. The birth of the town of Kolmanskop happened just before the creation of the Sperrgebiet.

In 1905, Johnny Coleman got stuck in a sand storm and abandoned his ox wagon there.

In April 1908, a worker on the Lüderitz-Aus railway line, previously employed in a diamond mine, found and presented a shiny stone to his supervisor, a hobby mineralogist from Germany who recently moved to Namibia to keep a 20 km long stretch of railway free of the ever shifting sand. That was the beginning of the diamond rush (full story here or there, from which I copied part of the following text).

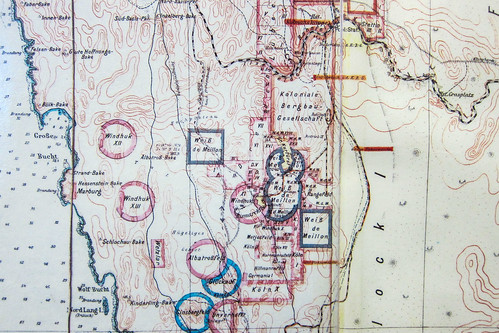

No later than September 1908, the German colonial government declared a Sperrgebiet, or “forbidden zone”, extending 360 km northwards from the Orange River and 100 km inland from the coast in order to control the mining of the diamonds, and in February 1909, a central diamond market was established.

Kolmanskop grew quickly through the 1920s, until 1928 when much bigger diamond reserves were discovered near Oranjemund, at the southern end of the Sperrgebiet. By 1938, most of the workers and equipment were moved there. The CDM headquarters moved to Oranjemund in 1943, mining operations ceased in 1950, and the last inhabitants left Kolmanskop in 1956. It was abandoned to the elements (and the sand and wind are quite tough here), until the 1980s when it underwent renovation for tourism purposes.

To cater for the 300 Germans adults, 40 children and 800 Owambo contract workers, the town had, among other facilities, an hospital, a bakery, an ice maker and a dining hall. It was apparently a pretty little town in the desert, and completely electrified! A hundred years later, it’s only a minority of African rural areas that can enjoy electricity. It is also worth noting that the hospital boasted the first X-ray machine of Southern Africa. To care about the workers? Not so much, it was more about scanning workers suspected of having swallowed diamonds.

The sheer wealth generated at Kolmanskop (peak production was over 30,000 carats per day) is demonstrated by the way in which water was supplied to the town. Every month a ship left Cape Town carrying 1000 tonnes of water, and each resident was supplied with 20 litres per day for free. Those requiring additional water paid for it, at half the price of beer. The lack of fresh water to power steam engines also forced the building of a power station which supplied electricity, very advanced technology at the time, to power the mining machinery.

“It also possessed its own wine cellar. The wine was moreover used medicinally. One of the two resident doctors believed that patients recovered more speedily if they received some stimulation in the form of a little wine or champagne. Another doctor, an excellent surgeon, had a less exotic conception of health-giving additives. He encouraged his patients to eat a raw onion daily.

In 1927 a magnificent new recreation centre was built where many functions and forms of entertainment were held. It had perfect acoustics, designed by an expert from Germany. Provision was made for gymnastics and film shows. There was also a large skittle alley a casino and a theatre. The various rooms were painted in different colours with artistic friezes, deriving their names from the colour used. An enormous kitchen with a high ceiling had unique features. The stoves stood in the middle of the floor, leaving ample working space all around, and the chimneys were placed under the flooring.” (source)

After all the villages through which I cycled, it’s hard to believe that this comfort and entertainment was available in Africa, in the middle of the desert, 100 years ago.

After WWI and the retreat of the Germans from Namibia, followed by the South African rule, the diamond deposits around Lüderitz were considered depleted and the claims were sold to Ernst Oppenheimer, here founding a company called “Consolidated Diamond Mines of South West Africa (CDM)”, which was later merged into the De Beers group, and controlled all diamond mining in the area until entering into partnership with the Namibian government in 1995 under the new name of Namdeb.

Sir Ernst Oppenheimer was a German who got familiar with the South African market by selling diamonds from the Cullinan Premier Mine, where the largest rough diamond of gem quality ever found was discovered in 1905 (which was cut and integrated into the Crown Jewels of the UK). He founded the Anglo-American mining company in 1917 and became the majority shareholder of De Beers only nine years later, thus contouring a company profiting from a global monopoly over the world’s diamond industry until today. He stated in 1910 that “common sense tells us that the only way to increase the value of diamonds is to make them scarce, that is to reduce production“. We all know the “A Diamond is Forever” marketing that followed to manipulate consumer demand.

There is a 30-minutes documentary called “The Case of the Disappearing Diamonds” (starting here on Youtube), where it is explained how Oppenheimer/De Beers/AngloAmerican exploited the Sperrgebiet and stole diamonds off Namibia, rushing in mining the high-grade blocks only before the unavoidable Namibian independence. Without it, could the tiny Namibian population be richer than Qataris today? The documentary features Bernt Carlsson, the UN Commissioner for Namibia who died with the bombing of the PanAm flight 103 in Lockerbie, and that makes it very prone to various theories (there’s more than enough of Jews, diamonds, American military, uranium, apartheid government, etc, around Carlsson), as can attest the pages hyperlinked to this sentence. The documentary is worth watching for the aerial footage of the Sperrgebiet and historical footage of the mining, and also for the nostalgia of the quality of TV productions in 1987.

The short tour ends after the guide manages to make the hundred year old history come alive again, explaining how was the cool air of the ice shop re-used at the neighboring butchery, how the parties were held in the concert hall, how people could pay their beers with diamonds, etc. I am then left alone with my favorite, exploring ruins, and the daunting task of visiting all the buildings before the site closes.

From the extreme east of the ghost town, I spot buildings further away. These were where the proper mining works happened. Is it possible to go further only with a permit. Some 15 km this way is located the Elizabeth Bay mine, an old mine that became a ghost town, and re-opened relatively recently. We can see it clearly on the satellite picture, as well as the ruins near the beach.

From the Sperrgebiet history book, I have written down the following figures, but I can’t remember to which mining area of the Sperrgebiet they refer. In the first 7 years of discovery, from 1908, the mines produced a total of 5.4 million carats (at $1000 to $3000 per carat today, it was a pretty good business for picking up shiny stones in the sand!). One and a half million carats were excavated between 1926 and 1931, with the assistance of 40-ton haul trucks. With the advance in technology and the high-grade area being mined, the diamond density fell from 7.59 carats per 100 tons in 1987 to 3.67 in 1996.

There are more ghost towns in the Sperrgebiet, like Pomona and Bogenfels. I’d like to return to visit Pomona one day. It looks like this, and it’s here.

The award of the missed opportunity of the century goes to the British: “Mining in the Pomona area started in the 1860s. After the discovery of guano deposits, the British annexed a number of islands off the coast of south-western Africa. This action led adventurers and traders into the area. Two of these, Aaron de Pass and Captain John Spence, obtained mining rights from Chief David Christian along the coast between the shore and 15°50’ longitude. Together they established the Pomona Mining Company and unsuccessfully tried to extract copper, lead and silver. It later appeared they must have shoveled the diamonds away to get access to the ore deposits. […] Official diamond mining started in 1912 under the auspices of the Pomona Diamanten Gesellschaft (Pomona Diamond Corporation). This mine soon extracted an average of 50,000 carats (10 kg) per month.“

Unlike Kolmanskop, these remote places can be visited only with a permit and a guide, it costs money and needs preparation (police clearance).

“In the early days, in the nearby Itadal Valley, stones were so accessible that prospectors with no mining equipment would crawl on their hands and knees in full moonlight collecting the glittering stones.” It has nothing to do with the mining of diamonds in kimberlite pipes like in South Africa.

For those who like exploring-travelling on Google Earth, the Sperrgebiet is perfect. There are more ghost towns, excavators (like this cute one), remains of railways, … to discover in a 350 km x 100 km deserted area. There was a 119 km long industrial line (600 mm gauge) linking Kolmanskop with Bogenfels, completed 1913, the only rail link in Namibia ever electrified. The rail track does not exist anymore.

Resuming the tour of Kolmanskop:

I have described my encounter with the fashion industry a week ago at the Kanaan farm, and it seems Vogue really likes Namibia. A model was photographed in 2011 for Vogue UK on that very same diving board above. And it seems fashion photography has something for models nonchalantly walking in the desert with cheetahs and naked tribal men …

I went to the top of the the mine manager’s house. Built 100 years ago, abandoned to the wind and sand 50 years ago, but it looks robust enough I could almost move in tomorrow.

Because Kolmanskop ghost town is THE tourist attraction of the area, every tourist going to Lüderitz stops here. And my loaded bicycle, somehow secured by being obviously displayed between the café and the parking, inevitably attracted some uninvited spectators interested in cycling (a.k.a the Germans).

One of them notices my Rohloff speedhub and tells me about Pinion. I’ve been very satisfied with my 14-gear Rohloff hub, and never thought that it was not necessary to have a this cumbersome big speedhub inside the rear wheel: it can be set in place of the bottom bracket! That’s what Porsche gearbox engineers have developed: a 18-gear gearbox for bicycles (reviews here and there). Apparently, it requires an even lower maintenance than a Rohloff, with a better placement regarding the bike’s gravity center, and leaves the rear wheel free from unconventional spokes. Sounds perfect for touring! Many German frame builders have incorporated it already. And if the name of Porsche gives it instantly an image of quality and reliability, it affects also the price tag: good Pinion touring bikes start from 4000 €. Anyway, cycle tourers would buy it only once there’s enough of “I’ve used it for 10 years and cycled around the world without any problem” on the internet.

On my exit of Kolmanskop, I snap the only building that is not in ruins: the blue hangar hosts a functional scanner , as it is where all workers and visitors of the Elizabeth Bay mine are supposed to check-in and check-out. So much for overrated small shiny stones! But as the diamond industry recalls, they are a bit like the Robin Hood of trade and industry: creating jobs for the not-so-skilled and helping some African countries developing better living conditions (provided they don’t fight over it), all from people rich enough to buy these stones. A Robin Hood with lucrative intermediaries position though …

I started this blog post talking about the Aus-Lüderitz railway line. I still plan to visit the abandoned stations along my road back to Aus, but it will be in the next post.

We will be 2wd tourists, but will carry extra supplies, as we normally do, if we see any fellow 2wb (bikers). Any hints, warnings or dangers associated with wild camping. We prefer being out on our own than in campgrounds most of the time.

We will be using tents.

thanks,

Martin

Bonjour JB.

Super voyage, vidéos et magnifiques photos. Merci pour le partage.

J’aimerais aussi faire un voyage à vélo en Namibie à la recherche de dispensaires de santé (je suis infirmier), est-ce que tu peux m’aider? En as-tu croisé un?

Merci d’avance et très bonne suite

Salut Paulo,

Je dirais qu’il y a un centre de santé dans chaque petite ville ou gros village, et au moins un hopital dans chacune des rares villes moyennes, vu que le pays tourne plutôt bien ca ne doit pas être difficile à trouver.

Awesome JB. Thanks again for sharing. Can’t wait for the videos 😀

Thanks! I just finished the Namibian videos, 2 x 20min for 4000 KM. Finally done with editing!

Bonjour,

Je trouve cet endroit magnifique à la fois par sa désertification et à la place que la nature qui a repris ses droits sur les constructions humaines. Je te souhaites un agréable voyage avec ce magnifique vélo et profites bien de la vue magnifique de ce pays.