Bernardo says that the smoke from the gas flares killed all the food in the area. But luckily, he has access to drinking water with the solar-powered pump/tank system installed right by his house. Since there is no water in Soyo, people sometimes drive to his place to make a refill.

The local language is called “Fiotte”. People in general also speak Portuguese. It is not a separate dialect like kriol in Guinea-Bissau, but is Portuguese with few imported local words. For example, Bernardo tells me that peanuts are called “jinguba” in Portuguese and “jinpinda” in Fiotte. In reality, both are local words, “jinguba” is not Portuguese, but rather Angolan-Portuguese.

Today is Independence Day, a national holiday. I will learn later that what I am told is wrong, it is actually another holiday, Independence Day being on November 11th. But it doesn’t matter, after breakfast, when I am about to leave, the rain starts and the sand road turns into a muddy pool for 4×4 only.

It is already a struggle without the rain, so seeing my shoes being swallowed into the road, I accept the suggestion of Bernardo to stay with him the whole day and leave tomorrow. Spending the whole day in a village can be boring. Fortunately here, there are kids to play with.

I share Bernardo’s daily activity for a while: sitting on a chair, looking at the road and drinking. Since we finished the vinho do Porto, he brings on the whiskey. An oil company stopped here last year and gave him a box of bottles and a tee-shirt. I guess the technique of the colonialists to easily and peacefully get slaves and resources still works well today, independently of the skin color.

I’m pretty sure he didn’t drink a single drop of water since I arrived. He is 82, drinking and smoking all day long, and doing very fine. Working hard is maybe more harmful to the body than alcohol and cigarettes. So here we are, sitting on our plastic chairs, sheltered from the rain, watching the trucks passing fast on the road. Every time we hear one approaching, Bernardo shouts “Chinese!“. He says that “Chinese work day and night! And they don’t go to church on Sunday, they only work“. If the truck driver later appears to be black, we say “Ah no, Angolano“. And that’s it. We don’t have to do anything since the wife is cooking.

The meals here often consist of “funge”, which is no more than the local name for the soft fufu. When the whiskey is over, he brings on boxed red wine. I show them pictures of the worms I ate in Congo. “Ehhh, cume bichu! No, we don’t eat this here. Only Congolese and Chinese eat everything. And the Chinese, they eat dogs“.

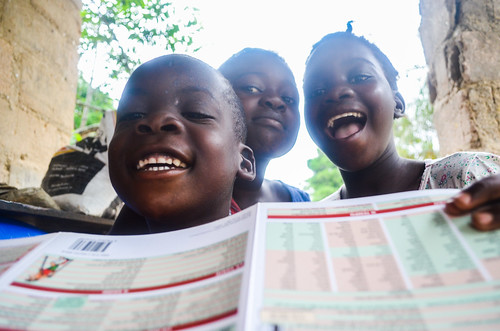

I have with me a Portuguese phrasebook I had bought in Congo. On the back cover, there is a world map. The kids can’t place Angola on it. Neither can the adults. Later on, a man who comes in for a drink struggles to identify the 5 continents. It is true that a map with the right projection makes Europe appear ridiculously small compared to Africa, especially considering how the old continent is “grand” in the mind of both Whites and Black. But this man is the school teacher, it’s not a good sign for the kids …

It rains continuously until 2 pm, so I will stay with Bernardo one more night. I spend the rest of the day teaching the kids how to take pictures with a dSLR and how to play frisbee with a box cap. It’s more fun that braiding a beer bottle and watching trucks passing by.

“The Zaire people are too many in Angola“, says Bernardo. Zairois is how the DR Congolese are still called. It is confusing as this province of Angola is named Zaire too. And it’s logical that Congolese massively move to Angola, the two countries share a lengthy border and one is rich, getting richer, while the other is … well, the other is DR Congo. The bread of Kavugi is made by a Zairois. However, many of them I’ve talked to speak a French no better than my Portuñol.

Very kind during all my stay, Bernardo sends me off with bread and roasted peanuts. The road is now dry (more or less) and I can continue on the sand road.

The sand is actually still freshly wet in some parts, dry and too deep in others, but I can almost cycle all the time. Though I lose lots of energy in low gear on a flat land.

I hear loud noises of machines operating in the bush. I make a stride aside of the road to explore: these are onshore oil wells, rotating under the sun, and surprisingly there is no one to guard them or to prevent me from taking photos.

It is very hot outside and half of the many trucks on the road are driven by Chinese. Most of them are driving with a cigarette in mouth.

The road meets the ocean and this is one of the rare occurrences I am cycling along the coastline. There is there a small market, delicious fried fresh fish and … potatoes! It’s so rare. Fried potatoes. My food options have been so limited I am happy whenever I eat something different.

The road is getting very bad, with pools of sand. It is passable as long as I cycle slowly, hold on tight on the handlebar, and avoid to put a foot down.

I see sometimes one or two platforms in the sea. The oil fields are mainly around Cabinda and Soyo, so these are maybe the last ones I see during my journey. The inhabited coast is populated only by palm trees and would make a perfect place to camp.

Many Angolans give me the thumbs up. They are many to request photos as well. It is surprising for a country without any tourist and where someone with a camera is a spy. Perhaps it is the best time to visit, while tourism has not picked up and the people are still genuine? It makes a very pleasant cycling day despite the sand mud road.

I thought I would make it to N’zeto in the day, but it was over-optimistic. I had roughly estimated the distance to 100 km, but it is actually closer to 160 km. With the sand, it takes at least 2 days.

My coca-cola stops are here called gazosa stops. Gazosa is the name for soft drinks and I find coca-cola almost everywhere. However, the glass bottles are often not available, and I have to buy cans for 1 USD. As usual, everything is two to three times more expensive than what I have been used to.

What I find particularly annoying are the “experts in tourists”. When I stop I am always approached by people for a chat. It’s fine, but they never listen to me. There is always, among the crowd, some guy who will say louder than others, that I am doing a world trip, funded by my government, and that I earn a lot of money for it. Everybody is convinced that I am paid for cycling. And no matter how hard I explain them that it’s not the case, they will always believe the loud “expert in tourists” who has never left his country and whose talent for bullshit earns him respect. They are also convinced that the satellites are watching me every minute and that I am assisted by my government as soon as I have a problem.

It kills my mood, as I am living on the cheap and my only activity is to meet people. But those ones believe I receive a lot of money and they think they know more about my trip than myself. Then, there is little to exchange …

From Mucola, I turn east to meet the asphalt of the new road until N’zeto. One of my toes is very painful, with pus, and I need to change shoes. The ones I am wearing since departure are well enough worn off anyway.

The police stops me on the road for a passport control, and I take the break opportunity to get a gazosa and to walk around. There is an old bridge and what looks like an old rusty tank nearby. But one policeman whistles me, comes back after me and say I cannot do that. I am just taking a walk around the old bridge. “No, you are a tourist, so you must stay on the road!“. OK … well it’s good that I didn’t take my dSLR out of its bag then, I may have been arrested for spying! With a 27-year long civil war followed by a no-visa policy from the government, people don’t know yet what tourists are. Of course I won’t stay on the road and I will take pictures of everything I see, but the lesson is to keep a very low profile next to police checkpoints. I will also do regular backups in case someone asks me to delete pictures from the SD card, and will not upload anything on the internet until I leave Angola.

I continue onto cycling the nice tar road until N’zeto, a small town but the biggest one in a 100 km perimeter, where I don’t know yet where I will sleep. A few kilometers before town, a Toyota Hillux stops and Ahmad shows interest. And the wonderful magic of cycle-touring strike again: he offers me to stay at his compound of employees of a large Lebanese engineering and construction company. They are the consultants for the road works I have just been passing through.

At their camp, I can enjoy wifi and a hot shower: a paradise! It is wonderful to camp in the wild, but it is also a pleasure (and necessary in order not to get crazy) to stay with expats once in a while: they seem to be the only ones who have a clean house, with A/C, electricity, hot showers, various topics for discussion, and good food. They are like an oasis in the tough Africa. In average, I get to enjoy a hot shower at one location per country. Cold showers where the water comes from above are rare too. Most of the time, I only have a bucket on the floor and my hands to splash water onto my body.

Since my toe is in a bad shape, my hosts also take me to the project nurse. And we buy 4USD trainer shoes, the largest size available at the N’zeto second-hand market, which are slightly too tight.

After a precious rest day with Ahmad and Kifah and a breakfast of za’atar (thyme, sesame and olive oil), I am ready again for a long day on the empty paved road. There are so few cars, even when the road is brand new.

Some people hail me to get their picture taken. Other drive slowly next to me to snap me with an iPhone or a tablet, through the car window, without asking. It is a bit strange for a country where authorities think a picture = a spy. And also very annoying to have cars driving slowly behind me just to observe and snap me. Well, I may be the most interesting thing they have seen in their country since the end of the conflicts.

As I stop in a small roadside settlement to take photos of bush meat hanging in the sun, I make a wonderful discovery: the best bread I’ve eaten in ages. The lady invites me to snap her and shows me how she makes bread with nothing: a simple hole in the ground, covered with a iron sheet and wood fire on top.

All in all, I have met a fair number of people who can speak some French. It is because they have been schooled in Zaire during the civil war.

I escape the tar road to take the old road to Ambriz, a coastal town. Even though every one told me to remain on the tar, this dirt road is a very scenic one. And there is no one, very quiet. On the other hand, big biting flies prevent me from stopping or from cycling too slowly …

With the absence of people, it is easy to find a nice camping spot near the lagoon.

The lagoon is filled with salt. It is the Ambriz nature reserve. I see a small springbok in the morning, as surprised as me to wake up each other.

I run out of water. The first humans I see are the immigration officers recording my details as I move from the Zaire province to the Bengo province. I make them feed me with liters of water of a bad taste before they can see my passport. The town of Ambriz has less than 20’000 inhabitants, but a large military base, in front of which I refrain from using my camera, and a port for the oil & gas industry. The most interesting is to wander along the gravel streets of this dead town, as usual too hot to be outside, among ruins of Portuguese colonial buildings, old houses still inhabited, some new houses, and kids playing outside while a few adults rest in the shade. The quietness and the decaying impression I experience make me feel in the Far West, while I was in the jungle a few days ago.

Surprisingly, the road from Ambriz back to the main highway is paved. I can cycle on faster, especially on the main road that has long stretches of nothing.

When leaving Ambriz at 11, I knew I made the mistake of not eating anything for lunch. I was happy enough to find a cold coke. As a result I eat the rest of my chikwanga cassava stick, just to tame my hunger. I am sure they eat better than me in the International Space station. Now I am seeing the end of the journey, I know my cassava diet will soon be over. And finally, considering the scarce availability of transportable food here, a stick of cassava is better than nothing.

The highway is brand new, with machines still working on the sides to make the rainwater drainage system. When some gravel stretches, untarred yet, appear, it becomes very very dusty. I can say now that I am definitely out of the rainforest. It looks a bit like Senegal, not illogically reflecting the symmetry with the Equator, very dry and hot, with baobabs and thorn trees.

My lips get dry no later than ten minutes after downing half a liter of water. I have no problems drinking one liter in a go. I drink the people’s water, a bit yellow. There are no pumps here and few rivers, and I don’t know where they fetch it.

At the end of the day, I cross another police checkpoint, where I am not stopped this time. There are many people bathing in the river, it makes me envious, but I can’t really join them. I already tried twice to jump into a fresh river, but there would always be a kid spotting me, and inviting all his friends to watch me naked, standing next to the river and saying nothing. I prefer the discomfort of going to sleep with a dirty skin to the awkwardness of being observed by a crowd while bathing in a river.

When I stop at what looks like a school, in Libango, I am told by the wives that it is actually a construction company office. The men are away or playing football and Filipa and Elena invite me for dinner, and later giving me an empty room when they see me building my tent.

“You can’t take photos. it’s forbidden“. That is what I heard from a man stopping with his car as I am snapping the bush meat. Forbidden to take a picture of the road with a dead animal? Why is this random man saying that? I don’t know. Some people are liking pictures, others are paranoid about cameras.

After a chain cleaning and a quick lunch in Caxito, at my closest to Luanda, I head east towards Uige. Caxito is just 50 kilometers away from Luanda, but I have no interest in visiting the capital city. “Most expensive city in the world“, “the only place of Angola that has banditos” … I don’t hear good things about it. It would surely be interesting to see a brand new city, to witness how the rich people live, surrealistically fed by petrodollars in a huge country where most of people eat cassava and maize every day. But it is not worth the risk of cycling vulnerably among 4×4 in crowded streets to end up having to choose between a 40$ pizza and a 200$ hotel room. I’m sure they are cheaper ways to live it, but having witnessed crazy prices in the countryside, I am not interested in struggling in the capital city.

The long road from Luanda to Uige is marked as scenic on the Michelin map. Well, I don’t find it particularly scenic, and worse, the traffic picks up. Especially with the trucks. I have to make way for speeding trucks, all driven in convoys by Chinese. Chinese build the roads (and many other things), they exploits the quarries, and unfortunately for me, those quarries are along this road.

From 4 pm to sunset are my favorite hours to ride. It is not too hot, a little windy, and the subtle warm light makes everything beautiful. These conditions make me cycle until the last moment. I pass the town of Ucua, which has electricity, but continue. I am at 97 km for the day, so I will push it a bit further to make a mentally satisfying 100+ km and to sleep in a quieter place.

But as soon as I pass Ucua, the surroundings change instantly. It had been quite cleared up, offering the possibility to camp anywhere. Now, the jungle is back. The bananas plantations are dense but they make the best options. The road is narrower and winds through the tall trees, making the last hours of the day even darker. It will be night soon and I must hurry to find a lucky camping spot. In the same time, I hear branches constantly cracking around me. It is not a human presence. The noise is loud, it must come from reasonably heavy monkeys. I only spot one but they must be many. It reminds me a story from Xavier: a man should always carry a lighter with him to enter a dense rainforest at night. Not to make a fire, but for gorillas. If one gorilla kidnaps you to carry you until his camp, the fire from the lighter is the only thing he will be scared of, and your only chance to be dropped down. This, of course, belongs to the category “unconfirmed stories from Africa”, alongside with “the ultimate trick to survive a crocodile attack once he has his jaws clamped down on your body“.

But with so many branches cracking around, combined with the wild forest, I am not keen for camping anymore. And of course, this is the moment where humans and hamlets seem to have deserted the area …

I am now sweating a lot, trying to cycle as fast as possible, with sore muscles, until the first house. Sweating in the last minutes of the day is unpleasant, because I know my clothes will stay wet until the next morning. As bad things never come alone, it is during this lonely moment into the rainforest that the “Slope: 10%” sign decides to appear. Pfff … I’m too tired.

Still, I need to find the next settlement. Fortunately it happens just after the hill. I am very relieved to be in a way “saved” at the last moment, but I try to keep my joy inside to go and speak to the chief.

I explain my situation (my portuñol now works well) and request a safe piece of land to pitch my tent. He then takes a serious look and answer:

” -No.”

I am disappointed. Of course, when things go bad, it can be really bad.

“– No, you cannot stay with your tent here. We will give you a room.”

Ah! Much better. The room is actually a small mud house, with a hard bamboo bed, onto which I inflate my air mattress. They offer me raw jinguba (peanuts) freshly harvested, and raw crunchy cassava, to eat like a radish. I ate it this way a long time ago, in Sierra Leone. It is anything but tasty, like a bad radish. Then I learnt it was a toxic aliment if not cooked properly. And now I have it raw again. The truth is that cassava indeed contains cyanide, in quantities varying depending on the specie, and on the conditions under which the plant grew. There is enough cyanide in it to kill a rat, and boiling the root is a way to decrease the poisonous levels in it. I would eventually get a disease if I ate raw cassava every day.

The village is called Curva do Pais. I get water to shower and share the dinner with the elderly, funge and kinzaka: cassava fufu and cassava leaves. A whole dinner made of one single plant. I am thinking I must be, this past year, the White man eating the most cassava in the world.

Leave a Reply