The bees are absolutely everywhere. It is with good reason that the rainforest is called until Lastoursville “la forêt des abeilles”, the forest of the bees. They stick to my sweat, even on my face. They disappear in the evening, but only to be replaced by mosquitoes. It is completely impossible to stand still at the same spot (it is too hot as well). The workers of the future Chinese camp say it was even worse a few weeks ago, the bees prevented them to work. Bare-chested and hard-working in poor conditions, they couldn’t stand being in an open-air bee hive.

The Gabonese workers work every week day and get only a tiny holiday at the end of the month. They are on a camp with no phone coverage, no electricity, fortunately at least a water borehole, and I doubt the Chinese pay them well. We swallow half a baguette each and pack water: it has to make us last for 57 kilometers, during which we won’t find anything edible.

This section of the road, from Carrefour-Leroy to Mikouyi, is under construction. The Chinese have already built the roads around Franceville and they continue towards the Lopé National Park. Chinese are buildings roads (among others) all over Africa, and this is not a myth.

I would say Gabon is the perfect place to truly feel the jungle. Just walk, if you can, five meters away from the road, and the almighty vegetation completely surrounds you. It is like this almost all over the country.

In the forest of the bees, it is not possible to enjoy a break. Bees are always there. As soon as we stop, they come to investigate our clothes.

The bees don’t sting if we don’t do anything. After a minute, they are already about 20 of them on my clothes. We just have to be tolerant and let them walk on us, they will eventually fly away once they realize we are no sugar material. The problem is that they also try (and manage to) sneak under my shirt, into my pants legs, into my eyes. Maybe we are sweet, or maybe they like human sweat. It is hard to keep calm when bees are wandering under my shirt. While I take the tripod for a photo, Cyril can’t stand it and cycles back and forth to get rid of them.

After about 30 kilometers of dust and bees, we reach the “big Chinese camp”. It is also a work in progress. It will later welcome the workers for the construction of the road. We stop for a while to watch them drilling a borehole for a water pump. They have basic equipment (not the all-in-one truck that we see sometimes) and they say it takes one month to drill down to 90 meter. Well, they don’t say anything, the Chinese just drill and speak only Chinese. The Gabonese do the talk.

The way Chinese work in Africa can be surprising. As contractors from a relatively wealthy country working in a relatively poor country (although the GDP (PPP) per capita in Gabon is twice higher than in China, but GDPs mean little when wealth redistribution is an alien concept), I would expect them to bring in money, good equipment, technical knowledge, and as little workforce as possible. Just enough to manage and possibly supervise. Labour in Gabon should be cheap, and as in many neighbor countries, there is a lot of youth unemployment, partly due to a “the-government-must-provide” ideology.

However, I have the impression it doesn’t work this way. In several instances, I have seen Chinese employees driving trucks and doing basic manual jobs. At the borehole site, they are two operating the machine, and the five Gabonese workers are sitting around.

The reasons behind it, that I have heard several times, sometimes as rumors, sometimes as truths, is that: 1- the Chinese workforce is partly made of prisoners. They can reduce their sentence by being sent on African projects, where they are confiscated their passport and where they are not counted as regular employees (the contractor is thus lying to the authorities commissioning the project with foreign workforce regulations). 2- they are paid even less than Africans. I can only tell for sure that their living conditions on construction sites are much closer to the locals than to Western expats. 3- they can’t communicate in French or English, and they don’t like / don’t want to work with the locals.

It sounds easy for the Chinese to win contracts. They can complete work in due time for very cheap. They have little Western competition. They don’t bother about corruption, environment, ethics, labor regulations, minimum wages, etc. China has cash, so they can pre-finance great projects in Africa in exchange of long-term concessions and special prices on raw materials. They don’t mind lending money to unstable states that will likely not refund. They don’t have (yet) the negative image of the Western colonial powers. Nobody else is, directly or indirectly, helping the low-income populations as much as them; they bring in useful products and projects that the French can (or will) never offer. For example, in francophone countries, France’s share in trade flows shrank by more than half in the past 20 years.

On the other hand, they start to be seen responsible for slowing down the industrialization of the continent. Chinese products are always cheaper than anything made locally. The future role of China in Africa is very interesting, their investments seem proportional to the resource potential of each country (map1 map2). Could the term Francafrique be replaced by Chinafrique?

After more than 50 kilometers of cycling, we finally reach the “first village with food”. It is an achievement, but we are once again disappointed by the Gabonese who don’t cook food for sale. We eats loads of those fresh beignets and buy spaghetti at the Malian’s. It costs here 1000 CFA for 500 g, twice more than usual. The rare Gabonese owning shops can be quite unfriendly.

The only source of decent water in the village is in the Chinese camp. They made their own borehole with taps. The water pump of the village is broken. We meet local workers who complain that the Chinese don’t give them contracts: they are paid on a daily basis (if they are paid). Locals and Chinese all work in pretty poor conditions …

The road after this village is ugly: it is being enlarged, graded, and prepared for surfacing. A solid large bridge is being built on each and every stream. There are too many machines taking the rainforest down, too many trucks on the road, and too much dust for us. It is like riding for kilometers in a huge cloud of red particles; my skin is red. I’m glad I can’t see my face.

Between 5 pm and 7 pm, the bees disappear and they are replaced by the fourous. The fourous are tiny mosquitoes, almost invisible, that surreptitiously bite, and it’s too late when I notice the disaster: they cover my limbs with bites and the itching is unbearable.

We stop in Mandzi-Kida, a village along the road, with a broken water pump but with solar public lighting. The senator gave those brand new lamps two or three years ago to the villages of the area. They used to work well, until the morning, but they now shut down between 9 pm and 10 pm.

The only shower is in the river, and not any river: we are back close to the Ogoué. We go and shower at night, with a lantern, and ask beforehand, as a joke, if there are crocodiles. “Sure there are!“, replies cheerfully our host, the chief of the village. “But they never attack people“. Good to know.

There is an antelope in the village they just captured. Still alive, it is rather cute. The chief explains that there are many “Chinese villages” surrounding his. They build camps everywhere along the road they are building. They did not enlarge the road in Mandzi-Kida. They must destroy most of the wooden houses but the villagers are opposed: the compensation money didn’t arrive yet. The chief says he would get from the government around 25 millions CFA (40’000 €) for the 20ish houses under his chiefdom. It is a big amount of money, way enough to rebuild houses further from the new road, and this time not wooden houses but proper concrete ones.

By the way, he just finished building a new house, right where the road will extend. It is a common wooden house, but the concrete slab makes it eligible for a compensation when it will be destroyed.

Here also, they have hard time growing crops. Monkeys eat bananas and elephants eat the banana tree. The chief says the Ministry of Forestry is supposed to provide reparation money in such cases, but even after providing proofs (photos), the system doesn’t work.

As usual, villagers have no difficulties in selling bush meat. The antelope we saw yesterday is killed at 7 am and hung to a pole next to the road. A 4×4 stops at 7:30, money comes in.

I like the authentic nature of the dirt roads crossing a wild jungle next to a crocodile river. In a year or two, there will be an asphalted highway at the same place, and it won’t provide the same feeling anymore. Adventure seekers must hurry: all the roads dubbed as “worst road in Africa” will be perfectly smooth in the coming years. Well, I can’t say for how many years they will last …

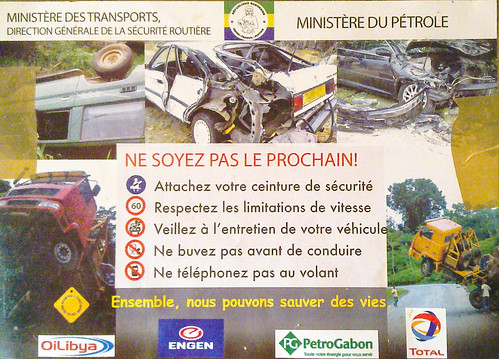

Not only the logging trucks, but also regular ones, are often equipped with steel bars to protect the cabin. That won’t motivate the drivers to use the brakes when they pass us.

“Y’a un Malien ici?” is synonym to “Is there a shop here?”. Most of the boutiques are run by Malians. It is either Malians or Mauritanians that provide everything in the villages. When asking the Gabonese where the next shops are in this rainforest desert, we were often answered about the presence of Malians, as if a shop is necessarily run by a Malian, as if a Malian can do nothing but run a boutique.

At one point, we find two Malians next to each other, and there is a reason: the main Chinese camp is here.

To my surprise, the contractor of the road construction is not a usual construction company, but SinoHydro. The company has been in Gabon for less than 10 years, and started with the dam and the hydropower plant of Poubara. They did a good job for cheap, and have since then been given many other projects, not at all related to hydropower. It includes the Moanda – Bakoumba road, where the French and the Gabonese have wasted 4 budgets within 20 years to pave less than half of the distance.

There are workers every five kilometers or so, mostly on the future bridges. The teams are often made of Gabonese with one or two Chinese. I keep asking them how to they communicate together, and I have yet to find the first Chinese who speaks either French or English. The Gabonese say they communicate together with signs.

We make a long break at a point where they dug a huge hole in the mountain. They are shortening a long and dangerous turn. I clearly see on my stats and maps that if a road is paved, it becomes easily 20% shorter than the unpaved one. Here, is it really needed to excavate a rock mass of roughly 40 x 40 x 150 cubic meters? That will be easily identifiable even on the worst satellite maps.

Several people snap us with their cellphone camera. I wonder how many cyclists they see.

The dirt road, the lack of food, and the dusty minute following each truck overtaking us are enough. After 306 kilometers of scenic but rough road since Alembé, in the Lopé National Park, we are happy to find the asphalt again. It happens at the Mikouyi roundabout.

It is the end of the forêt des abeilles. The forest of the bees is mostly land unexplored by man. Today is December 24th and the small hamlet is cheerfully drinking. We are happy to find cold drinks for 600 CFA ! It is still 200 above the price outside the bottling factory, but already 300 below the highest prices we have been quoted. The more remote is a location, the more it costs to supply cold drinks. The price of a coke (50 cl in glass bottle) or a djino (local Fanta) ranges from 400 CFA near the bottling plant to 900 CFA in the remote bush. Maybe even more if we had been to dead end roads …

The local beer however, la Régab, is always between 600 and 700 CFA. It is almost systematically cheaper to drink 65 cl of (warm) beer than 50 cl of Coca-Cola (warm too). The logistics are much better with beers: SOBRAGA brewery trucks regularly delivers the Régab anywhere in Gabon. Our drinking friends teach us that the true meaning of Régab is “REgardez les GAbonais Boire” (“Watch the Gabonese drinking”).

We are also happy to get large plates of chicken and rice for only 1000 CFA. We really come out of several days in the bush and a simple plate of rice with sauce tastes amazing.

We left early to complete the journey until Lastoursville, the “big town” of 10’000 inhabitants, to celebrate Christmas with exceptional food. Well, we just hope that we will find a restaurant and eat something unusual.

Lastoursville is named after François Rigail de Lastours, who founded there a trading post in 1883.

After spotting a pizzeria in town, which will be perfect for our Christmas dinner, we head to a remote hotel to negotiate the room price. “You are White so you have money” states clearly the owner. The lady adds that we are rich (for being White, naturally) and that on the top of it, “you earn a mosquito bonus, a sun bonus … you White people get paid for things we live with every day“.

She actually refers to the bonus earned by the forestiers, the people working in the forest for weeks in a row to get the wood out of it. But we are not expats, and not even earning a salary. Nobody believes it. It is really hard to explain to locals that no, we are not paid to cycle in Africa. “Oh we know very well, you are tourists and your government pays you to do what you are doing. Then, you will write a book and make big money“. I don’t know where they get this idea, that tourists are “paid by their governments”. Some even pay 15000 USD to cycle 4 months in Africa. No matter how vigorously we explain that we earn no money by cycling here, people are still convinced we are paid. Most of them can’t believe that two White men will spend a lot of time cycling in a place where there is nothing to see, just for fun. Well … the more I have these conversations with them, the more I start to think alike: it’s really tough indeed, and why am I doing all this?

It is frustrating to spend days cycling to meet people, and to hear systematically that “oh anyway, you get paid for it“. It seems that for people, knowledge is worth nothing. Experience is worth nothing. Only money is worth something. In my case, I worked to make money, and I am now spending it to visit a continent and meet its people. Those same people work to buy a beer. The notion of spending money to travel and discover places simply doesn’t exist (unless you have too much of it; it would make too many beers). Then, how do I feel rewarded?

The Christmas dinner plan fails: the pizzeria doesn’t work. The few restaurants that cook food make the same rice and chicken. We end up buying tin cans of cassoulet and lentils at the Lebanese supermarket … that will be our special Christmas food.

The heavy rain in the morning delays our departure. The power comes intermittently. We decide to leave well after noon, after changing the contents of my oil reservoir for my stove. The lamping oil is not working well, it makes a lot of smoke in the MSR stove and it’s a mess cleaning the pots after each cooking session. I replace it with the sans-plomb, the unleaded petrol that has been working best so far.

After the steep climb to exit Lastoursville, we will enjoy the perfect smoothness of the brand new road. Lastoursville is home to “famous” caves that have been pre-listed on the UNESCO tentative list, because of the strong human presence and cave paintings. One of them is located near Kessipougou, a village we cross in the fog. But we skip it as nothing is prepared for a visit: we would have to arrange it on our own (find a local and bring equipment).

We stop in a village at the sight of a big pineapple. Our discussion starts with the quality of the road. It feels so good to have a paved road and a power line running along it! The man explains that “See, the French (they colonized us) did nothing for us during the past 50 years. Look at the Chinese, within one year they did a good job!“.

Despite his views on development being necessarily passive, he invites us to eat the pineapple in the men-only wooden shack, where important decisions are taken and where women supposedly can’t enter (unless they bring food). Many men are already sitting there. The main topic of the discussion is very strange. Maybe the palm wine has been consumed for the whole day … “You White people have no values. You can see your stepmother naked. You have no sexual desire because you are used to see everyone naked, even your stepmother!“. It’s a bit of a shocking introduction, not only wrong but also misplaced, considering how many people I have seen bathing naked in rivers, topless old ladies waving at me, and men (and ladies!) talking to me while peeing in the bush. After a long exchange to figure out the root of this misunderstanding, it comes down to the previous job of that man. He used to work at the residential house of the French Ambassador in Gabon. He saw him once eating lunch right after a swim in the pool, and his stepmother was there, in bikini (not naked, then). I can imagine the situation very well, on a hot Sunday in a private nice villa. For that man, it was too much of a shock, and it’s all about the stepmother: it’s inconceivable to see her in bikini. The rest of the friendly conversation, about what is shocking/shameful/tolerated in Africa vs. Europe, brings us already to the night.

As a result, we stay in the case de passage of Bembicani. It is the home of Wongo, the warrior whose statue stands in the main roundabout of Lastoursville. There is no signal because the preferred network of the region is Airtel and not Libertis. Pierre Perret invites himself in the small village, as there is an interview of him on TV5Monde.

In the morning , the mist is still around in Bembicani. The road is not particularly high though, between 500 m and 700 m of elevation.

We pass the village of Mana-Mana. Kids call us Chinese, and it’s far from being the first time. It is logical since the Chinese were building the road two years ago, they must have been seen by the kids every day. When the Whites will be called Chinese more often than the Chinese are called White, we will know Africa has experienced a turn in history.

Here again, the only shop of each village, if there is, is the Malian. “Why only Malians run shops?“, I ask. I won’t hear the answer. A mini group of Gabonese has formed around me with the usual questions, “Where do you come from? Where do you go? Where did you leave this morning? Isn’t it difficult? Where do you sleep? Do you eat our food?“. The Malian will only admit that Central Africa is different. There are no food stalls like anywhere in West Africa. Only bars.

The Gabonese often say that for shopping, they go to the next large town, even if it is 100 km away. If everyone has enough money to take a shared taxi to go shopping, that could explain why only Malians bother running small shops.

The biggest village until Mounana is quite long. It stretches for about a kilometer along the main road. No food. It is really disappointing … we accept the idea that our lunch will be the can of lentils in our panniers. We continue a bit further to find a shaded and quiet area, and possibly find a Malian who has bread. Six kilometers further, there is a village but no Malian. The only food for sale is avocado. But they are not ripe. The next village, after another 3 kilometers, has a Malian. But he is sick, so the shop is closed. It is more frustrating than the Sahara! At least, there, when there is a village, there is food!

We finally find bread and soft drinks. Warm soft drinks, because the fridges are just big enough for the chicken and the beers. The bites of the fourous are nasty: I have twenty of them on each arm. It itches randomly during the day, several times, for five or ten minutes, during which I can’t help scratching. My skin will soon have wounds.

Mounana is another relatively large town, comparable to Lastoursville for the population, but not for the services. We cycle through it quickly, without finding water. The new road actually avoids the town center, if there is one.

There are many lakes around the town. Later, I will learn that we missed a radioactive expedition: Mounana was home to a uranium mine. Uranium was discovered in 1957 by the CEA, a company later absorbed by Cogema, and today called Areva. The mining company created there was called COMUF (Compagnie des Mines d’Uranium de Franceville) and owned by Areva, exploiting several mines.

Uranium has been extracted for 40 years, and the site is now closed. There is a hospital along the main road to follow the health of the people who lived or worked in the mines. It is said that radioactive materials have been buried on site and that workers today suffer from illnesses caused by the working conditions. What is proven is the presence of a natural nuclear reactor, the only one in the world, near Mounana.

This 100 km day ends in Moanda, where the French consul is waiting for us. Cyril had called him earlier to get information about the Congolese consulate in Franceville, and we end up for dinner at his house. His warm welcome makes me forget the past visits to French Embassies, but as he says, “Moanda is the bush“. And for us, it is the city (there is a pizzeria!). It is the 5th largest city of Gabon with a population of 40’000.

Moanda was built around a manganese mine. As a former Comilog employee, and present in Moanda since 30 years ago, he will tell us a lot of stories about Gabon, Bongo, mining, etc.

Thanks Vignesh!

I found there are many things to see around Pointe Noire on weekends too!

All the best,

jb

Hi,

I read your article, its fantastic. I am living in Congo, Pointe Noire. I wish to travel like you but unfortunately, my work does not allow me 🙁

Vignesh

Dear Vignesh, I’d love to see some pics of the old RTV Congolaise shortwave antenna or transmitter buildings at Pointe Noire or the Google Earth coordinates of where this radio transmission station once was if you can spare a little time.

Like you, I wish I could travel to these wonderful parts.