Gabon uses the CFA Franc, a currency to which I am well accustomed after visiting all the West African countries on the Atlantic coast. It is very useful to compare prices across countries, and Gabon appears instantly much more expensive. My points of reference are gone: even the Maggi cube, sold for 25 CFA anywhere else, is 50 CFA here (when it is not 75).

My first impression is that people are friendlier. My stomach’s first impression is that there is no roadside food: when the roads of Cameroons are invaded by ladies selling dishes from their home cooked pots, the roads of Gabon are very quiet. The shops are very rare too.

We finally manage to find bread in a village. A sandwich bread-butter-sugar is apparently the only food we can get until Bitam, the next large town. While we are chatting with some villagers, the chief of the village comes to us to introduce himself. He boasts about how he was selected to be the chief, because he is the one with “intellectual skills” (precisely, a Bac +2). His brother (brother-son-of-the-uncle, not brother-même-père-même-mère, so it’s technically a cousin) is with him too. While the brother is chatting with us, the chief, ignoring him, is stopping the conversation to take Cyril away and to show him the few bananas available. I joke around saying that this kind of respect must be included inside what was called the “intellectual skills” … and the brother instantly changes his tone: he confesses that the chief is bad, that he has more drinking skills than intellectual skills, etc. The previous chief was actually the (real) father of the cousin, thus after 5 minutes of funny discussion I could feel the resentment that has been going on between the cousin and the current chief for the last 25 years …

Bitam is the first “large” town of Gabon for someone coming from Cameroon. It is quite small: Gabon has a population of 1.5 million, the capital city Libreville gathers half of this, and Bitam, the country’s 11th largest city, counts slightly more than 10’000 inhabitants.

It is where we must stop for the immigration procedure to get our passport stamped. We must make photocopies of some pages of our passport, and the police officers, moderately friendly, send us to the shop across their office: the photocopy costs here 100 CFA. How come it is 100 CFA here when it is 25 CFA in all the previous countries I have crossed? It sounds like a nasty trick from the immigration post, especially as we cycle around and find another shop where it is 25 CFA.

I can’t tell if it was a mini joint business between the two or not, but what is sure, is that prices of Gabon, for the same basic services as in West Africa, are much higher. We were told that we call the Gabonese the “Whites of Africa”, just because they are rich. We are also confirmed that the Bitam immigration post can issue a visa on arrival, for the same price as in Yaoundé (50’000 CFA), but with probably much less documents required.

It seems Airtel SIM cards are out of stock in Bitam, as it is often the case for the operator that offers the best prices. As a result, we get a Libertis (Gabon Telecom) SIM card, and notice the prices of the cyber cafés: 500 CFA per hour, twice more than before.

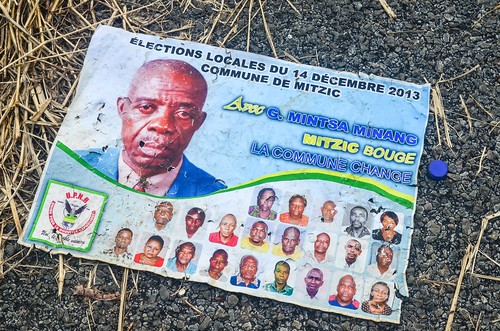

We cycle a bit further after Bitam until Awoua. We are invited at the house of man in exchange of money to buy the Regab’, the local beer. The teenagers take us to the local bar for the evening while the adults have their own meeting: they must prepare the municipal elections of tomorrow.

Usually, election days in Africa are wild and dangerous. There is a lot of cheating at the polling stations, lots of drinking, and, when the results are announced, lots of fighting, machetes, ethnic tensions, etc. It is the kind of days where expats are advised to stay at home. But we are confirmed that everything is always quiet in Gabon, and for small elections like these, nothing will happen.

Awoua is small town, or a big village, nicely equipped. There is a small solar farm powering the city water pump. It is pretty sophisticated. The public electricity is not here yet, but every group of houses has a large diesel generator, making Awoua quite lit up at night. The asphalt is still perfect on the road. In case all roads of Gabon are like these, I am not surprised the country can host a cycle race. If organizing a cycle race in Africa means finding first hundreds of kilometers of roads without potholes, it is not an easy job. The 2014 Tropicale Amissa Bongo race (named after the daughter of Omar Bongo) stops in Awoua.

Today is polling day. Every time we ask questions about elections, it makes people smile. We do it on purpose, because Gabon is a very stable country (where stable rhymes with limited freedom) that had only three presidents since independence. The current president, Ali Bongo, succeeded in 2009 to his father, Omar Bongo. Omar Bongo had been president since 1967, for 42 years, until his death. What if Richard Nixon and Georges Pompidou were still presidents in 2009? Well, it is not really comparable; Bongo Senior was only 32 when he first became president.

Ali Bongo’s party is called the PDG, where D stands for Democratic, just like the D in DR Congo and in DPR Korea . In 1979 and 1986, before the transition to a multi-party system, his father was re-elected by 99.96% and 99.97% of the popular vote. People tell us there are opposition parties today, but that they will vote for the PDG candidate anyway. I already had this discussion earlier: what is the point of democracy in a country where most of the population will ask around “who should I vote for?” Where people will vote for the candidate with the most impressive campaign (cars, gifts) “because if he can be rich, then he knows how to make us rich“? I don’t know how democracy is understood and applied in some recent constitutions. But the question “You have no roads, no electricity, and your president has been there for decades. Why don’t you use the vote to change this?” is too naïve.

The presence of France in the background of this pseudo-democracy is not to be neglected. France “restored” Léon Mba, Gabon’s first president, on the presidential seat when he was overthrown in 1964. France also sent in troops to stop the riots and “save” Omar Bongo in 1990.

In the 2009 elections, Obame had won the elections with 42%, ahead of Ali with 37%. Results have been reversed and published, and everyone, including the AFP, knew about it. It didn’t go to the press as if the whole world (but the Gabonese, the only one theoretically allowed to choose) wanted one president and not the other.

This is actually almost exclusively in order to protect the interests of Total (ex-Elf) in Gabon, which has been France’s main oil provider for a long time. There had been a French counselor to Omar Bongo, with an office inside the Libreville’s presidential palace. Gabon was apparently ruled like a small French department with Omar Bongo as a “super chief of the village”. There are many more crispy details in the documentary Françafrique – La Raison d’état.

Most of the conversations end up the same way. It starts with “You have no roads, no electricity, and your president has been there for decades. Why don’t you use the vote to change this?“. Then it goes through the fact that the Bongo family is slightly better off than the rest of the Gabonese (in France only, “at their disposal were 39 luxurious properties, 70 bank accounts and at least 9 luxury vehicles“…). And it ends with the fear of the war and the disorder: “but at least we have peace. We don’t want the war“. The most terrible examples of what unstable politics can lead to are just across the borders. Everyone fears to trigger another Angola, Sudan, Liberia … Africa doesn’t lack examples of post-independence civil wars and bloody conflicts following a power transition. No one wants this. So the current “stable” regime is in a way tolerated.

In the end, the country’s situation today is simply the logical result of: Africa-dependent unethical energy policy of first world countries + greedy careless local leaders + passive unambitious population.

We pass quickly through Oyem, Gabon’s 4th largest city with around 40’000 inhabitants. As usual, shopkeepers are from Mali, Guinea-Conakry, Cameroon, Senegal, Benin … (but what are the Gabonese actually doing?) The whole francophone Africa is represented. The work and residence permit is granted according to the geographical distance of the country of origin. For a Cameroonian, it would cost 600’000 CFA (900 €) for a two-year stay. And the price can go up to 1 million CFA for Mauritanians and Guineans (1500 €). This money is roughly equivalent to one year of average salary in West Africa, thus it has to be inferred that immigrants, “westaf’s” as they are pejoratively called, make at least twice more money than at home. On the other hand, French citizens pay only 50’000 for theirs …

Are the Gabonese really doing nothing and living off the oil revenues, letting foreign workforce run the country? Gabon doesn’t look like Dubai anyway, and I doubt people live very well, but probably better than the average in Africa. The poorest houses are wooden instead of built with mud bricks, but it is also because the country is a tree sanctuary (Gabon already gained attraction for its wood before the discovery of oil). Very often, houses have, whether they are made of wood or concrete, a CanalSat satellite dish on the roof, meaning they have a TV and a source of electricity.

Many houses look very well maintained, with mowed grass and a garden. By the way, I saw several grass trimmers used where I would “normally” expect a machete. Surely, Gabon is a step ahead in comfort of living. Machetes can do everything, from cutting bamboos to planting kassava, from slicing chickens to peeling a pineapple. There are many 4×4 on the roads, and people, especially the young, are dressed with style (well, hip-hop style, but clean). I also find that Gabonese speak a very good French compared to West Africans.

I heard once “Are you guys French? Won’t you stop triggering wars all over Africa?” but in general, anti-France comments are very rare for what it could legitimately be. I was also asserted once that “Africa is now supporting France, we are richer than you!” I am not sure it is completely true, although it seems to be the case already between Angola and Portugal. Among others, the daughter of the Angolan president Dos Santos is investing and injecting the much needed billions into the Portuguese economy. If the money comes from oil revenues, in a way taken away from the country’s development, it means that some European bankrupt public companies are saved with dirty money. For the record, the Angolan petrol company is the second largest in Africa. Its revenue is comparable with Air France-KLM.

“People of Gabon are nice but foreigners came to disturb“, the sentence resonates as in a wealthy country which need immigration. Cameroonians are numerous, especially in this border region, but they are not much appreciated. It is however true that Gabonese are very polite and respectful. We are always greeted with bonjours, when in Cameroon I would hear “Jesus bwahahaha!” and “are you Bin Laden? Bwahahaha!” way too often.

The Ntem river was marking the border with Cameroon, and now we cross the Wolem river. The two rivers give their name to the two departments of the Woleu-Ntem, one of the nine provinces of Gabon. Kids are jumping off the bridge under our lenses.

December is the transition between the small rainy season and the small dry season. We witness the same intimidating meteorological pattern I had seen first in Sierra Leone: within 10 minutes, the sky darkens, we hear the thunder, the sky turns almost black, the wind gets up, …. And then it rains cats and dogs.

For a long time, we thought this huge black cloud was moving around us, and that we could avoid it by playing hide-and-seek in the forest. But once the wind is up, the wise decision is to stop. We shelter in a “corps de garde”, one of those many wooden shacks built in front of almost every house in the villages, between the garden and the road. It is where people wait, chat and drink.

Once the rain is gone, we continue until Mimbeng, where we are hailed from the road by a priest, who takes good care of us, offers chicken, tell stories and keep us over night.

There is no electricity in the village of our host and his small generator is not working well. It had overheated the night before and it apparently needs a rewinding job. There is an electric line between Oyem and Mitzig, following the main road. The power towers look brand new, with the exception of one of them, down in the bush, cutting off the line.

The priest tells us the whole story: the power line Oyem-Mitzig, much needed to pull all the villages along the 120 km road out of the dark, was completed 7 months ago, ahead of schedule, under the lead of a French engineer. He logically wanted to power it up for testing purposes, but he was barred from doing it: the president Ali had to be there first to inaugurate the new line. As of today, the president has not come yet. The French engineer left the country and the project angry, and the brand new line is already falling apart without being used once. There is no maintenance scheduled to restore the poles taken down by falling trees, and the villages are still using their diesel generators. Sad but true story.

We also talk politics, because of the polling day, and we are happy to hear critics from a strong-minded individual. Even if at first, the country appears stable, quiet, and the people unhappy but satisfied enough, there is actually a real failure in the election process. First, the opposition is artificial: it is present but very weak and badly organized. They don’t hold on serious ideas and they fly abroad on election days. Omar Bongo was apparently good at letting the minimal amount of oil money flow down until his opponents, so as to completely tame the small million of inhabitants. Several (real) opponents with deep convictions have mysteriously disappeared or passed away at the hospital during a minor operation. Journalists can’t publish what they want, or they would lose their job.

The next day, there is no surprise: the PDG won the elections. Our host prepares an original breakfast, with vache-qui-rit cheese and a can of cassoulet. Cassoulet, what a good surprise!

So many things in Gabon are imported. It would be natural and logical to grow beans in the garden and eat local fruits, but it doesn’t happen here. The small shops sell mostly tin cans and the fruits are trucked from Cameroon. If you like good food, don’t visit Gabon.

Our first stop is the Mimbeng memorial to the tirailleurs Sénégalais, morts pour la France in 1914. This colonial infantry corps was not limited to Senegalese soldiers. In Mimbeng, roughly 150 kilometers inside the Gabonese land, they had to drive the Germans back, who were invading from Kamerun.

The road is as good as it has always been and the “hilly landscape” we were warned against is a joke. Gabon is not flat, but we can never see far away to the horizon. The vegetation is so high and dense that our field of vision is always confined to the road.

The highlight of the day is about fruits. We spot in a village locals eating lychees: “we got that from the big house, just further on the road“. Our mind is now entirely focused on finding the lychee trees, following the peelings on the asphalt for hundred of meters until the holy grail: a garden of lychee trees!

There is a large house in the middle of lychee tree park. The abandoned house is already starting to fall apart, as it belongs to a wealthy man who died only one month after the end of the construction. His brother and neighbors villagers come only to pick the lychees. Those fruits are not grown locally, it was just a wonderful idea of the late owner.

We eat as much as we can, and pack in our pannier as many lychees as we can. But it is a somehow frustrating situation: being full in the middle of an unlimited supply of delicious fruits, and knowing that we probably won’t find any until the end of the trip.

It is almost night and we must reach Mitzic. About 10 kilometers beforehand, we are invited by the SIAT guards to make a small tour of the rubber plantation. It is not different from the rubber plantations I have seen earlier, not only the giant Firestone plantation in Liberia, but also in Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast, and Cameroon. The hevea trees formerly belonged to Hevegab, and are now part of SIAT Gabon. Most of the production naturally goes to Michelin.

SIAT also gives out the robust bicycles I have seen around.

As it was recommended by the priest, we ask at the Mitzic parish to stay overnight. They have a small wooden house with electrical plugs for visitors. The children of the choir of the catholic school rehearse the Christmas songs.

During our night walk of Mitzic, we come across the most surprising prices: the hard boiled egg is 200 CFA (it was 100 outside Gabon), a spoon of beans is 50 instead of 25, a cup of bouillie is 150 instead of 50, a middle-sized pineapple is 1000 instead of 250, my Zakuro ginger soap is 700 instead of 400, the cheapest bottled water is 700 CFA (1 €), more than a beer … basic food is really more expensive, two to three times the West African price. Flour beignets are the only constant, they have the same size and same price. It is hard to find cheap food, there is nothing under 1000 CFA, where anywhere else it is always possible to get full with 200 or 300 CFA of rice or kassava. There are no ladies cooking delicious and cheap meals by the road, but on the other hand, stands of grilled chicken and beef are many.

It is a game to guess who come from where, among shopkeepers. All francophone nationalities of Africa are represented!

We must replace the USB adapter that Cyril burnt in the same time my micro USB charging cable stopped working. These are basic electronic cables, but not that easy to find. We must pay the high price (it is more than buying online with the shipping costs).

I enjoyed your gabon adventures and your pictures. Good to egt an insight from a bike traveller. Thanks for sharing.

Mbolo, akiba (merci en fang) pour cette chouette ballade dans le Woleu Ntem. J’ai vécu à Bitam et Oyem, et ça me fait vraiment plaisir de revoir tous ces endroits! Comme j’aimerai y retourner un jour! Le petit cimetière de Mimbeng a été rafraîvhit je vois, avec l’édification d’une stèle. Quand nous étions tombé sur ce cimetière il était envahit par la végétation et les plaques rondes étaient sales et noircies, certaines avaient disparues et la plaques d’hommages étaient taguées de signatures. De l’autre côté de la route et en contrebas il y avait encore de vieilles carcasses de véhicules rongés par la rouille et la végétation. La région était appelé autrefois “le nouveau Cameroun”. Comme vous, on allait par les pistes forestières se promener. Je lirai les autres pages plus tard car j’ai vu que vous êtes allés aussi au Cameroun. Bonne continuation dans vos voyages.