Roy sends us off with a big bag of UN food from the neighbors, that looks very useful, with many goodies independently packaged. We can pursue our road up to the north of Liberia until the Nimba mountain range and the Ivorian border.

The roadside is a collection of signs that makes the country look much worse than what I experienced.

With the civil war having ended recently, without enough trials and reconciliation, anyone we see by the road can be a former war chief or armed rebel. It is said that the youth making up the motorbike-taxis crew of Monrovia is mainly former child soldiers. Some war lords are ranking presently very high in the administration or sitting in the parliament.

The current situation doesn’t highlights with obviousness who did what and I can only imagine. While the Liberians are usually peaceful and polite, we are stopped once at a road shop by an old man sounding very rough. Reminding me of Jules in Pulp Fiction, he shouted all kinds of name-calling to express how good he feels today, and to force us to accept … his gift of bananas.

Kids call us with less “White man!” and more “Kuipoo!“. “Kuipoo” is the white man in Gio, “Kuiploo” in Mano, the two preponderant ethnic groups in Northern Liberia. I reply “Kuiti” which means black skin.

The road is being rebuilt by the Chinese and it really needs to. It is the main road link to Guinea and Ivory Coast.

I finally see palm wine at a road stall. I had heard of it many times before entering Liberia as being so popular but never got a chance to try it. This one is sold for 10 L$ (0,10 €) in a Club beer bottle. It is super cheap but tastes like a mix of lemonade with white wine left open for a week. In addition, it is warm from standing outside under a miraculously successful sun ray.

We reach Ganta for the evening, and after many discussions and waiting time to stay in a college, we are finally hosted by the very friendly Randall and Amina, with whom we share good times in the evening and morning until we leave. Ganta is almost at the border with Guinea. Guinea is just 3 km further behind the first hills. The Nimba county of Liberia is squeezed between the French speaking Guinea and the French speaking Ivory Coast, but since the ethnic groups of the region are the same (Gio and Mano), communication is possible in the vernacular languages. The Mandingo/Malinké group spread across borders too.

Ganta receives electricity from Ivory Coast. We finally see electricity poles, something rare for Liberia outside Monrovia and the Firestone plantation, following the road. Randall tells us we just have to follow them to reach Ivory Coast.

I break a spoke when leaving Ganta, which had not happened for a long time. The consequent delay due to the replacement makes me pass on a bridge just at the same time with the whistle of a train …

The Yekepa – Buchanan railway was used by Lamco to export the iron ore of the Nimba mountains from Yekepa, the northernmost town of Liberia, until the port of Buchanan. The mining activities were on hold during the war and recently Arcelor Mittal took over the mine. They restored the railway and the trains are running again. I haven’t seen any Arcelor logo on the pick-ups on the road, but too many BHP Billiton (who is in charge of the Guinean side of the Nimba iron ore) pick-ups and Total gasoline trucks.

I had the idea to cycle to Buchanan and hop in an empty iron ore wagon until the north of the country, but abandoned it after our unsuccessful experience with the Chinese at the Bong railway. Especially, it is a private railway, and unlike the popular Mauritanian one taking passengers for free, there are no signs of friendly hopping here. The train conductor smiled and waived at me, so maybe it is worth showing up in Buchanan one morning … The railway looks brand new, the wagons seem to carry mud and there is no passenger carriage.

Mount Nimba, or rather Mount Richard-Molard, sits on the borders of Liberia, Ivory Coast and Guinea. The iron ore of the mountain range, sometimes called the largest deposit in the world, is consequently shared by the three countries. Liberia has its ore railway running, Guinea is building its own until its coastline (1000 km of railway around Sierra Leone, instead of a 15 km connection to the Yekepa one, so as to be independent from Liberians), that I had seen earlier, and Ivory Coast has plans to build one until San Pedro.

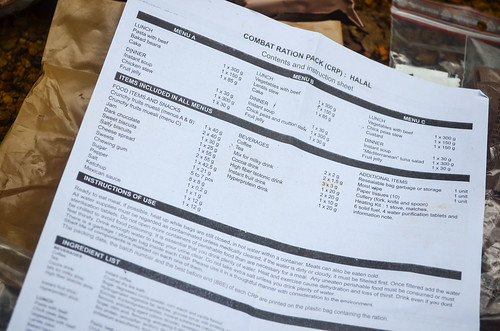

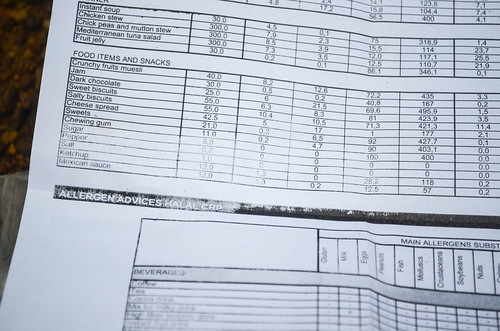

The road is unpaved, sometimes rocky, sometimes muddy, and it is hot … There is no convenient food stop so I fall for my “UN combat ration pack”. This is a perfect food supply: packaged in Spain, it is 1.4 kg and contains a small stove with heating tablets, eat-hot-or-cold lunch and dinner packets, a chocolate cake, sweets, coffee and tea, sugar, chewing gums, isotonic powder for drinks, water purifying tablets etc. I eat the the food cold and it is delicious anyway. This package is perfect for taking to the bush, just add water.

The downside is that, with my expertise in heavy food disappearance, I eat the lunch and the dinner within 10 minutes. I don’t know how it is supposed to feed soldiers in action for a whole day, but it’s definitely too small for a cyclist day!

Around Sanniquellie, the last large town of Liberia before entering Ivory Coast, we see more Ghanbatts than Banbats. The Ghanaian UN battalions are replacing the Bangladeshi ones.

Sanniquellie is where the presidents of Liberia, Ghana and Guinea met in 1959 to found the OAU, replaced in 2002 by the AU (African Union).

After Sanniquellie, a smaller track takes us to Loguatuo, the border with Ivory Coast. We follow the electric poles. It is supposed to be the worst section of the route (since we didn’t take the legendarily bad road to Harper) but luckily, there is no rain today and the surface is dry, fairly OK to ride.

Some 30 km before the border, we stop in Zorgowee for the night and look for the commissioner. We wait at his house but he is busy with an important council with visitors from other villages, so his son Obediah takes us to his home.

Obediah and his wife let us stay in a spare room. For this last night in Liberia, it confirms that the hospitality of the Liberians is great. The moon is full so our outdoor bucket shower is powered by the moonshine and a surprising sky of stars. With the rainy season and a permanently covered sky, it has been a long time since I didn’t see stars.

In the morning, the people walk by to go to the fields. It can take up to one hour waking to the field of rice, kassava, with a coupe-coupe for only tool. One man sees my cycling gloves and shows the blisters on his right hand. I won’t give away my cycling gloves and get blisters myself, but since I had lost a glove in Guinea-Bissau and bought a new pair in Guinea (which is why I have gloves of different colors since then), I have still a spare right-hand glove at the bottom of my panniers. I gave it to him, and in an exulting happiness he started to chop Obediah’s garden and request photos.

There is a light rain falling during our departure to the border, but the road mud is quite packed so it rolls on well.

I spot a Kingdom Hall of Jehovah’s witnesses in almost every big village. The electricity poles from Ivory Coast are still here, albeit connected to no houses. The road after Khanplay is even worse but fortunately not muddy.

I stop in Lapea II to refill water and am invited by Samson to try the GB (jeebee), again something that I have heard about a lot and can finally try before leaving Liberia. It is Nimba’s favorite food. It is actually just a kind of fufu (a kassava dough) with a different consistency. We eat it with a spicy soup of fish and cow skin. It is supposed to be MY experience, but THEY stole it: the real experience is the village watching me. The whole population, adults and kids, are trying to get a place by the door and the window to have a look at me. They seem a thousand times more entertained by watching me eating GB and cow skin than me finally trying this food.

In Loguatuo, the border exit is smooth. All in all, except the strange interpretation of the 3-month visa, all the officials we met in Liberia have been courteous and honest.

This stops as soon as we cross the bridge to Ivory Coast. There are 4 checkpoints in a row: gendarmerie, anti-drug, vaccines, and immigration. The first ones ask for a present but we skip this step rather easily.

The second officer, representing the anti-drug unit, makes us empty our whole panniers. I am used to that, it is very annoying and lasts for an hour. When the officer sees I am unpacking and repacking everything without showing a bank note, he would let me go.

This one is different. He finds our first aid kits with anti-malaria tablets and puts it aside. He claims we need an prescription for it, which is wrong: we only carry medicines that anyone can buy in a pharmacy (well, this is not completely true for Malarone, but we have no prescription and the officer has no clue which medicine requires a prescription or not).

He is clearly wrong by confiscating all our medicines on the basis that any medicine in Ivory Coast requires a prescription and self-medication is forbidden. He would let us go only after having filled his report and confiscated the tablets, unless we “find a solution”. Determined not to give any bribe, and not to abandon our precious medicines, we spend more than an hour with this guy discussing about anything. He is stubborn in maintaining his nonsense about the drug rules of Ivory Coast and our only weapons are humor and patience.

Eventually, after threatening that we will sleep in his room if he keeps us that long, he lets us go. We have seen a couple of Liberian ladies going through the anti-drug process as well.

Officer: – What’s in your bags?

Ladies: – Nothing much … a bit of food … (showing the contents of the bags)

Officer: – OK. You know the service? (without even looking inside the bags)

Some helper, whispering the translation to them: – It’s 1000 CFA

And that’s how we estimated 1000 CFA (1,5 €) the price of one wasted hour.

The vaccine checkpoint with the yellow fever card is smooth, and the immigration post as well: the officers stamp our passport without even looking at our visa …

All in all, the whole border-crossing process lasted almost 3 hours (30 minutes only for Liberia), and we have no more time to reach the first town, Danané. The area we are in is marked as red (“do not go under any circumstance”) on the travel advice websites of governments, because of the fights with the rebels hopping over the border. Yet, the Liberian immigration police told us the situation is quiet here now (there are still troubles in the south), and that we are the first cyclists to pass here. The previous ones had been turned down and the border closed.

The people call us “Kuipoo” like the Gio people in Liberia. The Yokuba group living here is of the same family as the Gio people. We notice the French influence in the first villages, the things that never appear in English-speaking countries: ads for Orangina, Canalsat dishes (in villages without electricity, yes), the use of the CFA franc, old ladies asking for food and money, the French in the news, the absence of English skills beyond “Aoayou?“, the people saying “Bonsoir!” from noon and “Bonne arrivée!” for a welcome …

Officially, Ivory Coast requested to be called Côte d’Ivoire at all times, but few outside the French-speaking media comply. Unable to reach Danané before the night, we stop in two villages before Samuel directs us to a school near his house. After a bit of cycling at night, we are welcomed in Blizreu and very well treated with placaly (a kind of fufu) and koutoukou, the sugarcane alcohol, with Honoré the chief of the village. As the custom seems to dictate, the border officials have made our entry into Ivory Coast very painful, but the villagers have restored our faith in humanity and hospitality.

Great Survey in the countryside. Your photos are very clear and are attractive.

j’ai vraiment aimé votre expérience. mais je voudrais savoir sil y a des véhicules en commun pour entrer en cote d’ivoire comme vous l’avez fait à vélo?

Hello, I really enjoyed your pictures in descriptions of the Liberian countryside. I’m currently writing a report on the mining sector in Liberia and was wondering if I can have permission to use one of your photos (the one the the Arcelor Mittal train).

Thanks again

Kayla