It is almost 8 am and we made sure to be ready with the desks and benches back in position. Unlike in Guinea, where they last four months, the school holidays didn’t start yet in Sierra Leone. Joseph had told us that the school caters for 250 pupils from the neighboring villages, but by 8 am there are barely 40 kids present. We cannot leave before taking group pictures with our Masankay hosts.

A probably difficult task for the NGOs fighting against malaria is to make sure their mosquito nets distributed freely are used effectively. They can be resold if a family needs money more than they care about malaria (very likely), or used as fishing nets (if close to a water body), but it is the first time I see them used as football nets.

The day on the smooth road goes fast. We have a second breakfast in Mile 91. Like Mile 28, the settlements along the highway are just named after the distance to Freetown.

After Mile 91, we are nearly halfway through Sierra Leone. We were warned that we would meet soon the Temne/Mende invisible border, where the villages are populated by the second ethnic group rather than by the first. I was expecting hear something else than “Apoto!” that nearly every kid shouts at us.

And as expected, the “apoto” suddenly disappears. It is replaced by something strange, not as aggressive as “Toubab!“, “Porto!” or “Apoto!“: the new word for designating the Whites is “Pomouy” in the Mende language. The roots are Portuguese for “po” and Human for “mouy”, and as usual, everyone by the road shouts “Pomouy!” as soon as we are seen. The small difference is that it is a very soft word. When all the kids say it together, they sounds like a tree carrying dozens of bird nests.

The pineapple price drops at the Taiama junction, between Mile 91 and Bo: while it was 3000 leones in Freetown for a small one, we get now 3 of them for 2000 leones (0.35 €). The junction, a crossroads between Yonibana, Bo and Mano, seems to be controlled by pineapple sellers. Children and ladies race themselves to reach first the cars that stop, with buckets full of pineapples on their head. The plantations must be very close and at the peak of the harvest. Any low price we quote gets immediately accepted, with fear that another seller runs to us. It’s similar with mangoes in Casamance: there are so many that it costs nothing. It would cost something only if there was transportation to somewhere else.

It is hard to stop on the road without making new exoskeleton friends.

Today is another 100+ km day and we plan to reach Bo before the night. The sky threatens to send us rain. It has been 3 days without it so far and we feel very lucky. As the night comes while we are still a few kilometers away, we have to be slightly rude at a police checkpoint to avoid starting a lengthy discussion about our trip, where we are from, what is our mission, how hard it is, where we will go next, … The policemen are always very curious and talkative, and since they have full power on asking for documents, luggage examination, donations, etc, it is an exercise of agility to make them understand we must say goodbye.

The colors are surreal. It is like if I am wearing pink sunglasses. The permanent layer of clouds over our heads creates a special atmosphere. We can feel the sunset through it but the dSLR cannot understand; it corrects it even in manual mode.

Helped by Peace Corps met by chance and a zealous mototaxi, we are directed to the (presumably) cheapest guesthouse in town, which has the good surprise to provide electricity! The sky breaks down no more than 30 minutes after we are installed, cleaning everything that is not covered along the road. Once again we feel lucky to cycle between the violent raindrops.

All in all, since this morning, we have had together rice and beans, heavy sandwiches of peanut butter and bananas, five pineapples, more bananas, many oily flour balls, rice and leaves, ending with two plates of attiéké (each) for dinner. Attiéké is like a couscous made of dried kassava, and in its full version (with fish, chicken, vegetables, spaghetti, egg, etc) it is delicious and filling. That’s more or less the double amount of what I’d need for sitting in front of a computer all day.

While the abundant rain keeps pouring and keeps the kids and ladies busy (they must run, pick and replace the plastic buckets at the edge of the roofs to collect rainwater), we watch the breaking news on the TVs of the Obama bar: the coup against Morsi in Egypt just happened. It reminds me of the difficulties of planning a trip across Africa until the bottom: anything can happen anytime and there is always a coup or a war somewhere in the continent. For many years, because of wars, West Africa has been an impossible route. It seems this year that it’s not worse than the eastern part.

Well, I only say “seems”, because there is a terrible gap between the reality and what is conveyed in the news. The news are exaggeratedly putting the accent on the dangerousness of some places. On the other hand, there is sometimes no coverage of very important news: dozens of killed with machetes in a capital city, political instability, etc. Even from inside a country, it is hard to know the situation at the borders.

After a restful night, we are invited to visit the wheelchair workshop adjacent to the guesthouse. There is a team producing wheelchairs locally. It is not uncommon to see disabled centers, the civil war in Sierra Leone lasted 10 years after all. It is more surprising to see a real activity of production that is not agriculture. Only the rims are imported as is. The steel bars come from Guinea and they are worked on, with everything else, in this workshop. They don’t receive any help from the government, as many of those touched by the war.

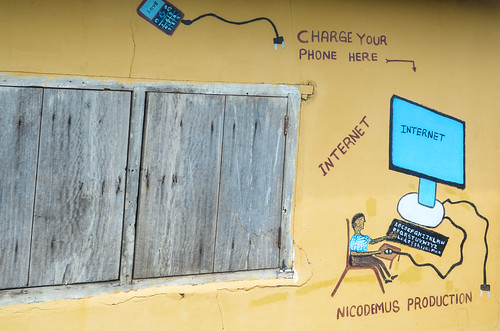

We spend the whole morning in the city Bo. It is a hassle to find a shop that can print photos. If I stay with someone along the way and we take pictures, I offer to send my hosts a couple of prints. It makes an unusual souvenir. Young people may have phones that can take pictures, but it still makes people happy to pose and see themselves. Most of the times, they don’t even have an email address, and since the postal service, if existing, cannot be trusted, it is another challenge to find the right people that will collect or deliver the photos.

The logical route from Bo to Liberia is to continue on the good road onto Kenema, the country’s third city, and then to cycle along the border until the crossing. However, we are advised not to do this because of the second part of the road, in a very bad state. Instead, the preferred route is to go directly from Bo to the border, through Potoru and Zimmi. The tar road until Potoru is not so good and the track afterwards is bad, not apparently not as bad as on the Kenema side.

One of the annoying sides of cycling in these countries is the complete absence of privacy. There is no awareness of what privacy or private sphere is. Being White and on a bicycle quickly attracts kids and adults. I must get used to being watched by a crowd when I eat, when I shower, when I talk with someone, when I repair my bike, when I put up my tent, when I read my map, when I type something on my phone (in which case someone will come and watch over my shoulder) … all the time. Even when I am talking on the phone and during bowel movement, some people don’t mind asking how I am doing and start a conversation.

It is impossible to pass through a village “normally”: some kids will shout “White! White! White!” in the local language, the others kids will quit their games and do the same, the adults and shopkeepers will step out of their houses, watch or call “my good friend, stop here” like an order. This is OK as long as I don’t get off the bike to buy something: if I do, the kids would gather around and watch me carefully. The same way I am describing my experience and interactions in writing here, they are inspecting and describing my bicycle, commenting together everything I do, repeating what I say. In real time, in front of me. The adults will come and ask too many questions, the same ones that I answer every day since I left. They will ask the same questions in turn as if they were not listening to what I have already said.

Most of the days, I enjoy it. I play the game and smile, and everyone is happy. It is part of the trip, and it is very nice to be able to interact with anyone. But if it happens I am tired, I cannot escape it. I can remain silent and make short answers, but kids and adults would still gather around me and do nothing but watch me. Everything I do and say will make people talk and laugh. I can’t just sit somewhere and enjoy the calm. For that, I would have to chose carefully a hidden spot. It reminds me of the joke about “what do you prefer … or having 30 ducks following you everywhere you go?“, because it is exactly what I am feeling. On the other hand, this problem is ridiculous compared to how kind and helpful everyone is.

The road is not so good but enjoyable, with very little traffic.

We stop next to a scene that could be a picture from the Stone Age. A family is gathered around a huge boulder, under which they are making a fire. There are smaller boulders, stones and gravel all around. They are stone breakers at work.

The fire has been ongoing for 3 or 4 days already. We can hear the rock cracking. It usually takes 4 to 5 days of continuous fire to break a big chunk apart. They will then crush it into gravel by hand, with a hammer. The gravel will be sold for construction, there is not even a chance of finding a diamond.

Apparently we have the same kind of “improbable job”, doing something that looks insane to the other: I am not counting how many times I have been asked “Do you take medication for the trip?” as if it was physically impossible (or maybe mentally abnormal) to cycle long distances (and I doubt the reputation of the Tour de France reached rural West Africa).

After a break in a village waiting for the light rain to stop, we continue until the tar disappears from the road. This is Bandajuma. It has basic houses that were built for Liberian refugees, but now occupied by Sierra Leoneans.

We take a small road downhill in Bandajuma, hoping that luck will offer us a shelter, which happens. There is a Muslim school at the end of the road, and the principal Mister Rodgers says he has plenty of unused rooms. We establish camp in one of them.

He tells us that the schools were almost not working during the 10 years of war. That supports the words of Peace Corps teacher met earlier, saying the math level is terribly low, and probably explains why at shops I am quite often returned more cash than what I should receive.

Leave a Reply