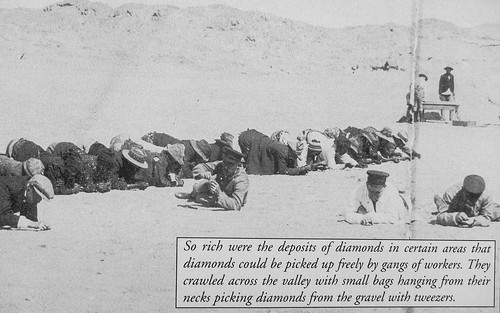

I find very interesting to learn about the Sperrgebiet for all the mystery that surrounds it. I already wrote a bit about it when I cycled through it from Aus. Namibian diamonds are sold by Namdeb through De Beers, which controls 80% of the diamond sales worldwide. Today, the mining only happens in Elizabeth Bay mine and in the sea by Oranjemund. There are less diamonds than before, much less than in the early 1900s where they used to be picked on the ground.

I clean my chain, hoping the damage from the sand the other day is reversible, and test it until Agate beach. We cycle together with Céline to that beach part of the Sperrgebiet. Maybe I’ll finally get there that tiny diamond paying for my trip expenses!

Agate beach is located a mere 8 km north of Lüderitz. On the way, behind a hill, is hidden a sewage plant. It’s a perfect way to spoil the desert with a nasty smell, but because it is leaking, it is also attracting all sorts of animals: grass is growing and plenty of oryx gather downstream of the plant! There are also springboks, and near a pond, flamingos.

So now, where are my diamonds? The beach has braai corners, looks like a nice weekend spot, but is rather dirty. I make a short swim in the sea (the water is at 12°C), and I try to imagine how the early miners crawled on the floor to pick diamonds, but it’s not that easy:

So how to spot a diamond among millions of little shiny stones? “When you find a diamond, you know you have one” is an answer I was told. Well, I find quartz crystals as shiny as diamonds, and there’s little chance I find two of them side-by-side to compare. This area has already been processed, probably several times, so we can reasonably think that the concentration has dropped as low as 1 carat per 100 ton, a point where it’s too costly to extract. One carat is a fifth of a gram, 200 mg. At a sand density estimated between 1.5 and 2, it means that a square of beach as small as 10 by 10 meters contains a check of 3000 USD burried at a bare-hands-diggable depth. Woohoo, that’s a lot of money, but a lot of work too. And prices for gem-quality diamonds (the ones in jewelry stores, not the majority that is only for industrial use) don’t follow any logical law, it’s all about what the buyer is ready to pay for. Gem-quality diamonds can nowadays be synthesized to obtain the same purity of a natural diamond (although the process is still costly).

Because I’m unable to identify a diamond on the beach, and especially because it’s sunset, we cycle back to the backpackers. At least I have seen a great wildlife for such a desertic place.

Oh, by the way, while visiting the oyster factory, we have seen a diamond mining boat coming back to the port. There are apparently seasons for harvesting diamonds, when the sea is safe enough for work. When there are not at sea, the boats return to the dry docks for repairs.

I had imagined a huge ship with a mega hose swallowing the whole seabed, but apparently most marine diamond miners here are independent and have this kind of small boat, a small hose, and a small rotating machine on board. Well, De Beers obviously invest in some real machinery, like this real 1.30 m wide hose (and the big ship coming with).

But much more affordable, useful, and tastier than diamonds, are oysters. Since I’m at the factory in Lüderitz that produces some of the best oysters of Namibia, let’s try them. And at 5 N$ (0.40 €) per oyster, as fresh as an oyster can be, it’s cheaper than my many coca-colas I bought on the road just to touch something cold.

We get a tour of the factory and an explanation about farming oysters. Their largest export is China. I can’t say I like oysters since I rarely eat any, and it barely tastes different than seawater, except when they are baked with cheese. Hmmmm …

I am supposed to rest for a few days, as I want to charge my energy and motivation levels to 100%. But I can’t leave Lüderitz without visiting a bit more than the town itself. Because it is locked into the Sperrgebiet, it is forbidden to go anywhere without permits, except around the 50 km loop exploring the peninsula.

Freed from my luggage, I venture on the peninsular dirt road (map). It makes a loop via Grossebucht and Diaz Point, passing first the lagoon, that I could maybe cross at low tide, but I prefer to stay away from the salt. The lagoon is where the Lüderitz Speed challenge happens once a year, during which windsurfers and kitesurfers compete for the fastest speeds. It has gone over 100 km/h and the latest “track”, dug in the sands of the lagoon, is visible on the satellite map above by activating the “hybrid mode”. The north/south parallel is striking: Lüderitz, a windsurfing hotspot, is on the African west coast at 27°S, far from everything, in the Namib desert, just like Dakhla is a kitesurfing hotspot, on the African west coast at 24°N, far from everything, in the Sahara desert. It validates the cliché that the cold and windy west coast of Africa is for surfers and adventurers, while the warm and quiet East coast is for divers and vacationers.

Grossebucht, as the name implies, is a (relatively) big bay facing south. From there, I try to spot Elizabeth Bay mine, unsuccessfully.

Playing finding diamonds can sound fun because it’s forbidden and potentially highly lucrative, but it’s actually super boring. Running on the beach after flamingos to take photos is much more entertaining.

I then cycle back via the coast. The map shows several names ending in “fjord” or “bay”.

The small island I can spot now is called Halifax island. It was used in the early 1900s as a guano mine, so I guess the two abandoned buildings there are related to guano. There should be plenty of penguins on the other side of the island (only visible from the sea, a good way to sell boat trip tickets), and dolphins and whales sometimes, but I don’t spot any.

And I finally reach Diaz Point, where Bartolomeu Dias built a cross in 1487, and where a 28 m high lighthouse is active since 1915.

It looked like this around 1914. I really like this Lüderitz area. There is a supermarket and a backpackers, which is all one needs, and the rest is rough, very windy. It’s a mix between Brittany and a desert. There are very few visitors, and I can understand it: Lüderitz is too far from anything, and has nothing thrilling to offer. The interesting linguistic fact of the day happens when I stop and have a drink at the super quiet Diaz Point café. The guy working there says “it’s half three” for 14:30, as a literal translation from German.

Behind the lighthouse, I get to practice my favourite game: visit ruins and try to figure out what did people do there.

I will see more ruins tomorrow when I visit the Kolmanskop ghost town, so I focus on the specialty of the Diaz peninsula: flamingos

I end the day at the waterfront pub where I get to speak Spanish. Indeed, sitting there are two officers of a Pescanova ship, a giant fishing company from Spain. They warn me against walking at night in Lüderitz. Seriously? After chatting a bit more, I learn that their lifestyle is rather arduous (sail the world, catch fishes, and return home) and they always sleep in their ship. And that, actually, they have no knowledge of Namibia. It reminded me traveling for work. Landing in a new place, I knew (at first) nothing about my new city, and the company policies were “do not go there, do not do that“. It’s surely safe this way, but also kind of a waste of time, to be in a foreign city and not learning anything. Lüderitz is a tiny place in the middle of nowhere, and nothing would happen here (I could also say “it’s Namibia, nothing ever happens”, which may be refuted only in Windhoek).

This Lüderitz break was perfect after my long dirt ride from Windhoek, a nice way to visit, rest, and wait for my passport. By the way, I received the notice that my new passport arrived in Windhoek, so I can start cycling back to Aus and find a place to leave my bicycle while I make a quick return trip to the capital city. Next stop: Kolmanskop ghost town!

Cycling through that remote godforsaken Namib desert alone for so many days was a daring wild adventure. Incredible that you survived through such loneliness.