I’m ready for another expedition on a very little used track into Damaraland. My visit of the old Uis tin mine is leading me to another mine, the Brandberg West mine. I was warned against the poor state of the D2342 and the absolute lack of water, but I have the feeling it must be worth it.

From Uis, with enough food and as much water as I can carry, I leave the straight road to Henties Bay to turn right at the gemstones sellers. They are scraping the rock formations and the old mines to sell stones on the road. Obviously, carrying stones in my panniers is the least relevant thing I could do, but it doesn’t deter the sellers from calling me to have a look.

When I turn onto the D2342, I know that I won’t see many cars. Actually, I won’t see anyone for 20 hours, until the next day. This road passes between the Messum crater and the Brandberg mountains until the Ugab river, and then turns left to the Skeleton coast. It’s a longer way to reach the coast, but because it meets it in the north at Mile 108, it gives me the opportunity to visit the Cape Cross seal colony without going back and forth on the same road. I have been cycling a lot in zigzags in Namibia so as to see the many attractions on a same curvilinear abscissa.

The road is actually not too bad and it offers another view of the Brandberg, from its southern side. The mountain range is quasi-circular and 25 km in diameter, which looks like a small distance, but I feel I have been riding around it for three days now.

It’s a really lonely road … I probably won’t see anything man-made until the Save The Rhino campsite in the Ugab river, after 100 km, which is my halfway stop for refilling water.

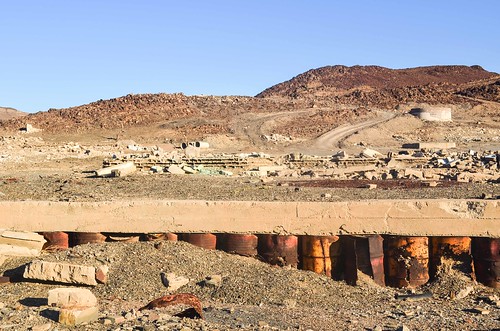

The landscape is bare with inselbergs that take ages to reach. I can sing and shout while cycling, it doesn’t bother anyone. Around 4 pm, I spot structures by the road.

The two brick structures without roofing are old mining houses. I have seen on a map of this area a label “Villit mine”, but I don’t know if this is it. The area is mostly flat with shallow yellow grass, so locals could drive anywhere to try informal mining. The cans piling up in a hole are well corroded by rust. These walls would make a perfect shelter against the wind and potential curious animals, but as usual, I don’t feel like stopping before sunset.

Maybe this was a bad idea. Soon, the wind rises and the few trees and shrubbery, present up to now, are completely gone. The main road is too corrugated and I follow the parallel track in a better state. There are dots on the horizon line, and these dots are moving. As I get closer, I realize it is a herd of springboks, and they run from left to right, crossing my dirt road, and jumping exactly in front of the setting sun, like in a movie.

They are too small to appear decently on a photo, but it was a magical moment. I wish there was a National Geographic drone silently flying over and delivering me the footage of a tiny cyclist with springboks in a magnificent landscape.

Finally, I reach in the last minutes of daylight the Messum dry riverbed, where a sand road leads to the Messum crater. I was hoping to be lucky and find another brick structure, like the old mining houses, but I will have to deal with the shrubbery. I set up my tent in the scary silence behind a large stone. I am most likely fifty kilometers away from the nearest human. The owner of the rest camp in Uis told me about a man living in a remote house and collecting gemstones, with a windmill where I could refill water if I don’t have enough for two days. Today, I used only 5 of my 10 liters during the day.

Namibia can really be worse than Western Sahara. I’ve not seen a single human since the turnoff from Uis. If the wind blows in the rocks, I imagine a car coming. If my jacket or the flysheet of my tent flaps, I suspect a curious hyena smelling me. Hopefully just in my imagination …

Twelve hours of good sleep later, I wake up in good shape. The bush is the best to have a perfect sleep, from 8 to 8. The Messum riverbed is so quiet, and past it, finally putting distance with the Brandberg mountains, the landscape is becoming even more desertic.

I realize I have lost a 0.5 L water bottle from its cage: bad luck. These road corrugations are guilty. The “water cost” of cycling back to retrieve it may be higher than the quantity of water I could recover. It is safer to visit the midpoint house with a windmill.

But there comes a convoy of 4×4 and I stop them to ask for water. They came from the most remote Damaraland tracks, where it is strongly recommended to travel in a group as the traffic is almost nonexistent (it’s where some years ago a Dutch tourist died after waiting for two weeks, stranded without petrol). The Germans give me plenty of water so I have enough until the Rhino camp.

The Welwitschia plants (welwitschia mirabilis) are endemic to a single region in the world, and it’s not the friendliest: from the Namib desert up to Angola. They are very special because they can live up to 2000 years old, in the desert! Their long roots allow them to survive in places where the rainfall is below 25 mm per year, which is roughly equivalent to two hours of heavy rain. There are male and female versions, usually not far from each other. Their two leaves grow between 10 and 20 cm per year, while they have a hard stem (cork-like corrugated bark) growing only about 1-3 mm per annum.

There is the remote house with the windmill. I don’t need to turn there as I have plenty of water now. The German tourists spared me 16 significant kilometers.

The scenery is gorgeously incredible. It’s not easy to cycle, but absolutely worth it.

There is no shade at all for my lunch break, but it’s not too hot, and I’m burnt already anyway. A second 4×4 convoy gives my a coke, I’m confident about making to the Brandberg West mine tonight, nothing could go better.

I continue and pass the turnoff to the coast. I am not heading straight there because I need water first, and the water point at the Save The Rhino camp costs twice 10 km. But it includes an old mine.

I can’t find on the internet a nice explanation for the magic rugged landscape into which I just entered. I remember a man telling me that an inland sea used to occupy this place. The Damara belt is 300 million years old and was formed as a result of tectonic plates moving towards each other and pushing the seabed upwards. Today, the broken down seabed is raised up, leaving 50-meter high plans, pitched at about 30 degrees, shadowing my narrow gateway. I call them the Damara stripes as they are clearly visible from satellites pictures.

It’s simply amazing. That’s a Top 5 of my best days of the whole journey. And it’s not over yet!

Among these vertical walls is hidden the old Brandberg West mine. This is an old worked-out tin mine which operated from 1946 to 1980. “Tin-tungsten mineralisation occurs in white quartz veins in the dark turbiditic rocks. The white veins are clearly visible in the walls of the large open-cast pit. Remnants of the original buildings, such as offices and living quarters, can still be seen here today.”

When I saw it on a map weeks earlier, I didn’t imagine I would end up in such an offtrack location. Now that I am on site, it’s time for exploration!

There is not a single structure standing up. I don’t know why and how, but for each house only the foundations remain. I know that locals on a bike trip sometimes make a stop here and take a dip, because there is a small green lake at the bottom of the open pit.

My original plan was to sleep at the Save The Rhino rustic camp, which is some 5 km further, because I would have water there. But now that I am in a special location, why not sleeping in the open-pit mine? I have done it in Liberia at the Blue Lake, and this one is much more desolate. It’s not that often that I have the opportunity to sleep in a mine, compared to the many campsites of Namibia. And actually I have enough water for dinner, so I don’t need to go to the camp now: I can take a swim and stay here overnight.

The water is crystal clear and green, maybe taking its colors from the Sn-W (tin & tungsten) deposits which used to be mined. The locals also told me that due to the high density of minerals/salt, one floats in this pond, just like at the Strathmore South old tin mine near Henties Bay, nicknamed the dead sea.

I would probably not dip in it if I didn’t know that it’s not harmful. Sadly, I don’t float in it, but it still feels good to have a bath, it doesn’t happen often. And to walk half naked in a mine.

There is a small shelter under some foundations but I decide to lay my mattress on the deck under the very nice sky.

My new day must start with fetching water. For this, I head to the campsite, but it’s not as easy as I thought. The road is terrible, only made of stones, and meanders inside the round hills. It takes me an hour to complete the 6 km to the camp, which is supposed to be in the Ugab river. And since I will have to go back on these same stones, uphill, I know it will be worse on the way back.

But the camp itself is a little surprise. The SRT Ugab base camp is a very secluded campsite in the dry riverbed, and the first structures I see are lunar modules that house the staff. It is a field camp for the SRT (Save the Rhino Trust) which aims at monitoring and protecting the black rhinos of Namibia. I thought I would see some of them, but there is nothing more than a small information room.

As usual for Namibia, this river has no water. But I have now the proof that water is flowing, as a pipe goes down directly inside the sandy riverbed and pumps water from the underground. It tastes salty, but eh, I need to drink as much as I can, and pack 10 liters for the road.

The exhibition from SRT highlights the skyrocketing rhino poaching and the alarming decline of the black rhino population (from over 100’000 in 1960 to less than 3000 in 1980), mostly motivated by the beliefs that Rhino horn powder has medicinal properties in China. Out of the seven subspecies of black rhino that once occured in Africa, two are already extinct and the five remaining are critically endangered. In other words, I would be extremely lucky to bump into a rhino like I did with elephants.

Now that my water supply is secured, I have no choice but to face the ten awful kilometers back until the junction with the D2342 and D2303 roads.

From now on, I expect a gentle downhill until the coast. I will meet the sea for the first time since Sumbe in Angola. The D2303 straight to Mile 108 is in a very good condition, but a new element comes spoiling my day: the wind.

The headwind is very strong. It’s so frustrating that, when I can finally enjoyed my deserved easy cycling, the wind decides to throw a spanner in the works. The road is almost a 60 km straight line until the coast, and there is no way I can avoid the wind.

Now it really looks like a desert. I am entering the Dorob national park. It means “dry land”, and there’s little space for contesting this name. I am cycling ridiculously slow because of the headwind, and I really hate headwinds in the desert: it makes you feel so powerless and useless. Yet, I don’t want to spend more time than required in this desert, so I have to waste my energy to compensate the resistance of the wind.

The Dorob national Park appeared in the news because of the shooting of a movie, Mad Max: Fury Road, which supposedly damaged the desert. And yes, it is possible to damage a desert. The ground is made of earth, sand and small stones, not too soft, but still retaining the tracks of vehicles. Even my bicycle can leave a track in it, and for sure large vehicles like in Mad Max do so.

The rainfall being very low, and the wind shaping the soil, the tracks left behind by a 4×4 going offroad can survive a hundred years. And it does make the landscape very ugly. Despite the many “no offroad driving” signs, the pristine views are often altered.

At the end of the day, I only cycled halfway to the coast. I thought I would easily reach it … but the wind decided otherwise. Besides cycling against the wind, something else I hate is having to camp in a bare desert with my ultralight tent when the wind blows. I am not confident when I see the weak aluminium poles bending under the pressure of the wind in the flysheet.

I keep the hope of finding something by the road, a bush or a big rock, until the last sun rays disappear. But I have to settle for a spot next to a small hill, covered in game poop, meaning that springboks or gemsboks probably snuggle there. I build two extra walls with large stones and look forward to the wind to die down at night.

Amazing doing that remote area by bike. I drove from Cape Cross to UIs 10 years ago using that road and even in a 4wd Hilux, it was a pretty lonely experience. Wonderful scenery but absolutely no-one about if you broke down. I just cannot imagine it be bike on your own.

True, I have wonderful memories of these remote roads.

To your comment, I feel more confident repairing my bike than a Hilux 🙂

What an amazing diary of your trip from through Damaraland. Awesome photos.Ireally enjoyed reading your story and seeing the beautiful landscape. thanks for the history & geological information too. I will be visiting the Uis & Brandberg area with the South African gem & mineral club from the 18th – the 25th April. Seeing your photos made me “hungry” to get there!! The last time i was in Namibia was 35 years ago.

Awesome. What a bravery it was.

Continue dans le désert le spectacle est certainement plus intéressant ( surtout au coucher du soleil ) , je partage ton avis sur la plénitude et la sérénité de cet instant magique ou le soleil disparait , il y aura une autre coupe du monde dans 4 ans !!! dans un quasi désert .

Hello , dans 100ans tu retrouveras les traces de ton passage à vélo.Toujours des paysages fantastiques , bon vent !!