It has already been 20 days in Angola and I haven’t even cycled halfway through the country. I knew it would be tough to reach Namibia within 30 days, and after I lost 3 days crossing from Cabinda to mainland Angola, I knew I would have to apply for an extension.

It has been confirmed to me several times that the process for the visa extension is quick and simple, at any SME (Serviço de Migração e Estrangeiros) in Angola. I am now close to Sumbe, the capital city of the Kwanza Sul province, and it is better to apply for it here rather than wait for Lubango. I might not arrive there on time, and the police are annoying enough when all my documents are in order. I don’t want to know what happens if my passport and visa were not valid. There is a rumor circulating that anyone leaving Angola with an expired visa must pay 150 USD per day should they overstay.

Sumbe is a mere 60 kilometers south. The road is not following the coast, but a few kilometers inland, and is quite boring.

I break the boredom with a coca cola stop halfway. I also find yogurt made in Namibia … hmm hmm, products from the South! I am on the verge of reaching the South African sphere of influence; every imported product so far made its way from Europe, Middle-East or Asia.

I also ask just out of curiosity: the simple roadside guesthouse rooms start at 60 USD. I believe I will never sleep in a guesthouse for the whole duration of my journey in Angola. And I understand now why the Angolan visa requires proof of funds with at least 200 USD available per day spent in Angola: it is not to refrain tourists from visiting, it is because without this money, tourists will really struggle! Unless they have a tent and a beard.

I reach Sumbe city after passing the campus of the INP, the Instituto Nacional de Petróleos. Sumbe is not really big and luckily I find the SME office just before the 3 pm closing time.

Their computer system doesn’t work, but they let me fill in the forms, pay 20 USD, and that’s all! I am surprised at how easy it is. Just as easy as getting the visa in Pointe-Noire and passing the border. I don’t have my extension stamp yet: only the big boss can do it, and I must wait for him.

What I didn’t know is that the big boss wouldn’t come back before 5. Two hours waiting in the office, seeing all the SME officers returning from the city streets and clocking out on the book. The big boss finally comes in, stamps and signs my passport and wishes me a safe journey. Easy! Easy for a country with a terrible reputation for visas.

These hours wasted in the office prevent me from leaving the city and cycle tens of extra kilometers. I roam in town, visit the beach front, where all the nice hotels are lined up, and end up at the large modern church to ask for a campsite. There is a mass service on, and I don’t see where else I could sleep, so I switch to emergency mode: leave Sumbe quickly to be able to find a camp spot before night.

It takes a good 10 kilometers, slightly hilly, before I am out of the suburbs. I take the road to Uku Seles, going into the mountains, instead of following the busy boring road on the coast until Lobito and Benguela. A man by the road told me there is a compound nearby for “professores brancos”, so this is where I am heading.

A few kilometers further, there is indeed a large camp, with electricity and lights (absent from Sumbe’s suburbs), and a tall Cuban flag right in the middle. Cubans have sent support and troops to the current ruling party, the MPLA, to defeat the UNITA and the Western nations. I guess they are seen positively here and the relationship between the two countries is amicable.

There are other large compounds nearby, and during the last minutes of daylight I go on exploring, see if there isn’t a compound with wifi instead of a Cuban flag, by any chance … and this is when the police catch me again. This time it is friendly: they are doctors of the police hospital and they don’t ask to see my passport. They invite me to come over for a chat and stay with them for the night. “You should always sleep with the police for your security“, they all say. It’s not true, it just shows that the police feel they are the only means of safety in the country.

We all sleep together on mattresses outside the house and talk about Angola. “The price of gas is too high! We produce it, so it should be damn cheap“. Gas sells for 60 US cents a liter and diesel for 40 cents, the cheapest I have seen so far, cheaper than Nigeria, but it’s true it could be cheaper. They try to convince me that Angola is a promising land. They say the health and security are the priorities of the government. It is true, policemen are everywhere, one in each village and many at corners inside cities. I don’t need to be convinced, I see already how the country is investing in the infrastructure, how new health centers (posto do saude) and new police stations are appearing in remote villages, how rich in resources the land is, how high the prices are, and how it lacks in basic commodities. There is plenty of space to start a business. People are ready to pay crazy prices for basic products or simple services. If one wants to get rich quickly in Africa, this is the place to be.

For sure, there is a lot of corruption, a lot of wasted money, and a poor majority, but the country is so rich there is enough pocket change to satisfy the population, estimated between 16-20 million.

“The problem is education: the best choice for quality education is to study abroad, there is not much to do within Angola“, he adds. I agree, in general Angolans are far from being the most knowledgeable people I know, but the civil war has to be taken into consideration. If two generations couldn’t go to school, it is not likely that the country will stand up smart immediately. On the other hand, asphalted roads, electricity and water are being rolled out progressively, at a pace I estimate incredible. Angola must have built more new roads during the past 5 years than all West Africa together.

These men are doctors for the police. “So what kind of injuries do you have to face the most?” I ask. Unequivocally answered with “accidents caused by drunk driving. It is inconceivable for drivers to drive without alcohol.” These words don’t shock me. That is also why I avoid all the main roads.

The police doctors strap new band aids to my ankle wounds. I have mosquito bites, which I scratched, that grew huge and won’t cicatrize. Unless it’s other kinds of biting insects. They are on my ankles, where the skin is always stretching while cycling, they keep bleeding and will fill and refill with pus. It has been a week now and I don’t know why they won’t heal.

Anyway, the light but regular pain is not keeping me immobile. I don’t like to rest in a place if there is nothing to do, like blogging, bike repairs or visits. I am lucky that a menina is selling doughnuts on the road just as I start my day, it means I can get the energy I need for what awaits me: a 1000 m climb.

Angola seems to have a pretty simple geography, but I didn’t expect this many hills. Basically, over the 2000 km that the country occupies between parallels 5°S and 18°S, the elevation makes a gradient from the coast to the interior: as close as 50 km from the coastline, the elevation can reach 1000 m. It goes above 1500 m if I move 100 or 200 km inland.

In other words, unless one sticks to the coastal road, Angola is never flat.

As usual, people point at me, shouting at their friends to come out of their houses to watch me. They can take their time, I am very slow. I am cycling (and pushing) hard to reach Uku/Seles.

It took me almost the whole day for 60 km, including 10 km of pure steep uphill. I am now above 1000 m of elevation. Welcome to the club “Africa above 1000“, where people wear big winter jackets because the temperatures drop below 25°C. On the other hand, I am still drenched and sweating.

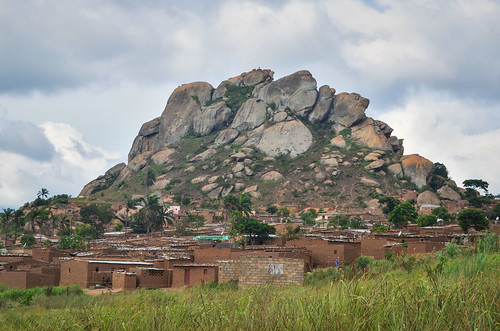

Seles is quite a big town for a small point on the map, secluded into mountains. It has many old style buildings. I find that Angolan cities, even small towns, always have a colonial center, either in ruins or half occupied by shops, while a thousand of mud huts congregate around as suburbs.

As I don’t stay in cities, I continue onto the dirt road to Catanda and Atome. The police doctors had told me not to take it. “It’s impassable!“. People from Seles say the road is fine, even with a small truck. As usual, I can’t trust anyone. It is on the Michelin map but not on Google Maps and OSM, just like the road that didn’t exist. Well, by now I am accustomed to impassable roads anyway, so the balance quickly shifts in favor of this dirt road.

The Portuguese are starting the road construction, even if it is an insignificant segment at the scale of the country, between two minor town. I am really impressed at how Angola is developing its road network. Despite all the accusations we can throw at the president Dos Santos, here the small towns are progressively receiving a better infrastructure than large cities of most of the countries I have seen. It must be a paradise for the Portuguese, Chinese and Brazilian construction and engineering companies, everything has to be built from scratch.

There are a few villages on the way, but they are almost indiscernible among the vast corn plantations. I find myself a nice spot in a corn field and set up my net under a farmer’s hut, in case it rains.

The night was chilly. Temperatures went down to 22°C and I had to wake up at 3 am to use my sleeping bag. Since I have barely used it since Senegal, it means I have been spending almost a year in countries where you sweat all day long, and keep sweating at night. Almost a year constantly above 20°C? I didn’t realize that ; what if I can’t bear below 20°C temperatures anymore? Perhaps snowboarding and Switzerland won’t work for me anymore …

The villagers wake me up at 6, just in time to enjoy the beautiful sunrise over the corn fields.

Kids are walking to school, all of them wearing their lab white coat, walking for a fair distance considering that I don’t see any school or any building for a while. When they see me, they start running all together, but only straight and on the road. I eventually catch up with them and then they stop running. I can’t tell if they are scared or if it’s just a mass movement: one starts running and they all follow. It happened several times.

The air is hot, the road is dry, but the road is much better than expected: the policeman said crap yesterday. This road is totally fine.

I can’t stay alone for a minute for a snack or a poo. There is always someone spotting me and following me. Watching me curiously. I can’t even say “Go away, I need privacy for pooing in the bush!“, as they’d all laugh and watch from even closer. These roads look deserted but they is actually always someone around.

The track follows the Quicombo river until Catanda.

The next big stop is Atome. There, the shops are depressing: the shelves offer only beers and tasteless crackers.

I had refilled my water bottles from a tap in Catanda, but I realized only later that they are now filled with green particles, as if the tap was delivering moss as well. The water was very clear so I didn’t noticed it.

Now in Atome, the only source of water is the nearby river where the boys wash their bikes.

The water of that river is murky. Is it better to drink clear water with a hundred green particles swimming in it, or yellow water? There was always hand pumps or water pumps in villages of the countries I have passed, but so often in Angola, villages rely only on the nearby stream. I am drinking the dirtiest water, and start using really for the first time my Micropur purifying liquid.

After bathing in one of these streams, I arrive at night in Chila village. It is the biggest one on the road, the most populated, but offers no more services than a tiny hamlet.

I tell my usual story to the chief and wait for him to tell me where I can camp. He repeats it to other men, modifying it a bit and adding that I am Chinese. Does it really mean Chinese because the only foreigners they see in these villages are Chinese, or is it a word that replaced Branco to designate anyone who isn’t Black?

Anyway, just like everywhere else, it is not knowledge that promotes one as chief. One hour later, a younger man offers me to sleep right at the center of the village. Hmmm … I won’t be able to sleep there. “What about there? It’s at the border of the village, better?” he says, pointing at a grass field where dogs and pigs run around, so noisy that I can’t even hear him properly.

A good sleep is a foreign concept here, and as I’m not taking naps anytime and anywhere during the day, I really need a good night. As they claim there are no animals around in the bush, and realizing the perfect moonless clear sky, I should be wild camping. I have enough pasta, tuna and water with me, so it’s a perfect camping night!

I cycle backwards a kilometer to find the right spot. It’s not easy to find at night, but it’s a pleasure once I am settled and eating under the stars. Until I see a column of huge ants walking directly towards my tent. I try to change the direction of the column, by walking on them in flip flops (not smart), and it fails. When I direct my flashlight at them, the ants make “Shhhhhhh“, like paper crackling in the fire. I didn’t know ants could hiss. They continue until my tent and I am forced to watch them do so, hoping that they will just pass through. Fortunately, one meter before, they disappear underground.

Every item of my gear is falling apart, one after the other. I had my shoes dying, my camera LCD screen that stopped auto-rotating, then the lens making strange noises during the auto-focus, and now it is the turn of my inflatable mattress. The inner compartments are cracking up and it now has a bloated end. Thermarest mattresses are really great, and the warranty will cover this defect called delamination, but it still adds a problem to solve asap.

My priority is to keep the bicycle 100% functional and arrive soon in Cape Town before a major break-down. I perform this morning the 5000-km Rohloff oil change, the last one of the journey. The cloudy sky is perfect to work on the bike and not to burn alive. But the flies are all over me, the tiny ones landing on my eyes and in my ears, so annoying that I hurry to clean my chain and sit on the saddle. I hear the first people I see saying “It’s the Chinese” once they see me from close.

There is nothing to eat in Chila. I am used to villages and small towns where people only cook for themselves, but it is always disappointing to reach somewhere hungry and have nothing to eat. I grab a can of frankfurters (that will make me sick) and am lucky to find bread near a river 16 km further.

I notice suitable camping spots along the road but I am too tired to make my tent. I don’t know what’s happening today, I am just too tired and could barely cycle 50 kilometers. I even fell asleep on a rock for half an hour after my lunch of frankfurters. I am not in good mood either, the clouds in the sky are likely to pour rain on my tent during the night. I decide to reach the next small village and ask for a shelter. I can feel small raindrops already.

It is Saturday evening, and the next village is already completely drunk before sunset. They all look like zombies. They come to me, barely able to walk or talk, to touch me and to hold my hands. Just like in a zombie movie, to top it off with bad breath. Today, I have already had three groups of youngsters on motorbikes annoying me, driving past me, laughing, driving back, laughing again and yelling stuff. They really have nothing to do there.

Luckily, there is one good man among the crowd of drunk zombies. He is Cumbano, and he is the barman. He and his wife are not drunk, and they very kindly put me up in the maize storage room for the night. It is a wooden hut with mud walls, but elevated on rocks, like half a meter above ground, to keep the harvest out of reach from animals.

I am ready to sleep but they invite me to have a look at the party. I barely party on this journey, and I decide to have a beer with them, even though I know a village party has nothing in common with clubbing in a capital city. The crowd of zombies is not dancing but only drinking. People speak Umbundu here, alongside with Portuguese. But they rarely carry traditional names, not even the family name: they will be called Jose Manuel, Armando Santos, etc, with no link to their Angolan ethnic group. Inside the bar, kids are sitting on the floor, watching the adults drinking until they can’t articulate a word. There are no smiles. Just people speaking with themselves, others looking for a fight. One old lady asleep on the floor, surprisingly no one stepped on her, ends up being woken up under the beating of another old lady. All of this under the eyes of the kids sitting there. One beer among them is enough and I can finally reach my makeshift mattress made of corn cobs.

JB your photography is getting better and better, with some of your photos being simply spectacular!

I especially love the “Corn fields at sunrise” and the last pic of the rocky mountain (just above).

Big kisses,

Miki

Thanks! Angola is a lot more photogenic too. You could introduce ballooning!