“Watch out for the logging trucks!“. Logging trucks seem to be the only danger in Gabon, and we were warned against them several times. The “grumiers” carry the timber (les grumes) from the forests until the sawmill or directly to the port. Oil makes up to 70% of Gabon’s exports, and timber comes second. The logging trucks can weigh up to 50 tons and everyone says they drive dangerously. We’ll see …

We say goodbye to Nervel and Clovis-Loïc, the seminarians of the parish, and leave Mitzic. We can’t find proper food in this town. Apart from the grilled chicken, we must deal with omelettes and beans.

The road to Lalara is very hot. Gabon reminds me of the Sahara because of the scarcity of food and the rarity of villages. It is very green, there are plenty of trees and rivers, but no food. And people pathetically consider tin cans of sardines as the local food. It is very frustrating to cycle in a tropical country where everything can grow, but where people don’t grow anything.

We cycle most of the time along the Lara river. The road is almost empty although it is the backbone of the country and the only paved road from Cameroon to Libreville.

We see many of the logging trucks. They drive fast indeed.

We stop for a coca-cola at the only village, equipped with a bar, in between the towns. The very small population of Gabon results in very quiet roads. There is no food here either apart from tin cans. If there is one thing easier in Gabon, it is about the payments: we don’t worry anymore about the change. We can pay with a 10’000 CFA bank note anywhere; people will always have change. The largest note that comes out of the ATMs is not as big in Gabon as it was earlier; it was almost impossible to pay a road side meal under 1000 CFA with a 10’000 note. In Gabon, big money doesn’t scare anyone. And even the smallest villages have their diesel generators.

Short photo stops can always turn into lengthy conversations. It happens when we stop at a lonely house by the road, in front of which an animal looking like a big ferret is hanging.

While taking the picture, I say for fun that we are representing the Ministry of Health and that we are making a report about the sale of bush meat. After all, police and immigration officers wear no uniforms, they idle around in colorful shirts instead. So why not two health inspectors on bicycles. On the election day, we were asked at checkpoint if we were the UN poll-watchers. If the gendarmerie can mistake two dirty cyclists for UN poll-watchers, we can probably usurp any job …

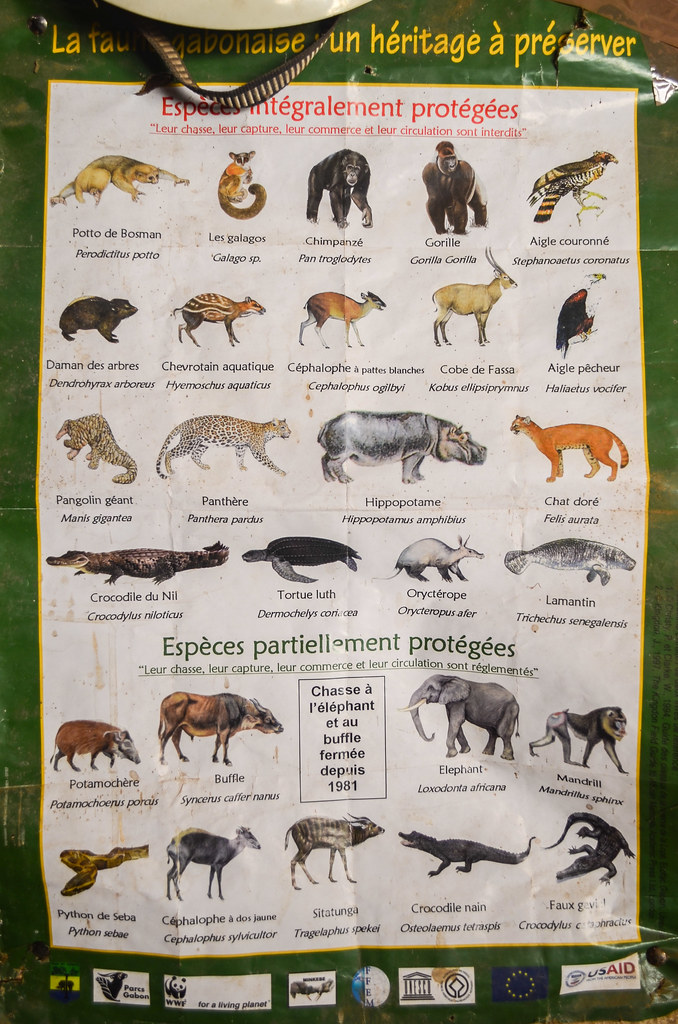

And it works! It even works too well. The villager starts a long monologue to explain he has no means of subsistence other than hunting and selling bush meat. Apparently, hunting bush meat is forbidden for endangered species, but tolerated if it is in small quantities. “Tolerated” has a broad meaning, it can also mean that it is allowed but subject to “fines” from time to time. Elephants aside, it is also very likely that people don’t know if the animals they hunt are protected or not. Most of Gabon is covered by the jungle and people have probably been hunting and eating anything that has flesh on the bones.

The concept of “national parks” and “endangered species” is relatively new. The villager vehemently argues that the government is making his life harder, by preventing him to kill the elephants and monkeys that come and destroy his small plantations. He says it’s almost impossible to grow anything because sooner or later, elephants will come and eat the crops. And as a result, we (we are still “representing the government”) must pay him compensations and subsidies for the fact that he cannot grow anything. His way to defend himself makes me feel that he must have had this discussion already, and that my joke is not far from a realistic situation.

I don’t know how true his story about elephants is. There are enough beers and cigarettes behind him. A car stops just after the house and a police officer walks towards us. At first, I fear that he will investigate why two tourists are introducing themselves as governmental health inspectors. The policeman speaks with us in English, we exchange a few words, while he bargains for the bush meat (he finally buys the animal for 5000 CFA (7.5 €)), and returns to his car.

Maybe I could have bluffed a bit further, by asking the vendor AND the buyer a “negotiable fine” for maintaining a potentially illegal business … if officials don’t wear uniforms and if the notions of law, interdiction, fine, bribe, protection, work, etc, are all mixed together, then we could totally abuse the image conveyed by our skin color to collect fines too.

At the Lalara roundabout, where the roads forks to Makoku, we skip the guesthouse and gather the food we can find. As a lady is cooking rice, we jump on the opportunity of eating something warm before heading further to find a camp spot.

We reach a Chinese quarry a few kilometers further. The West Africans who are working there inform us that we must first ask the permission to the Chinese if we want to take a picture. Cyril asks the Chinese man, who answers nothing, but stands there. He doesn’t speak French or English. The workers say they communicate with the Chinese with signs and a few common words. The Chinese actually understood that we wanted to take a photo of him, so here he is posing.

There is really no way to camp in the jungle. Every square meter that is not a road or a village is impenetrable jungle. Everything is so dense. If we can go somewhere, it means there is someone there already. Thus, after the quarry, we decide to stop in the Viafe village. As usual, we are directed to the house of the chief of the village to ask for the permission to stay here. Paul, the chief, welcomes us warmly at his house. As his wife says, he is just too kind.

His house has electricity all day long until the middle of the evening. It is usually the opposite: people switch on their generators only when the sun sets, and electricity lasts until there is no more petrol to burn. But here in Viafe, villagers get free electricity from the Chinese quarry during the day. And they have drinking water from a borehole that a French made some time ago.

The GPS on my phone sees all the satellites but I get no coverage. After a pleasant cold water bucket (it was really too hot today), they serve us bush meat: wild boar and rat. Gabon is a bush meat paradise. People take their rifle and go hunting in the jungle. There is only jungle anyway, and considered the small population, it is totally conceivable that when someone is hungry, he just goes hunting behind the house. Paul even shot a pangolin today but he couldn’t find it. I would have liked to eat a piece of this animal I have only seen in books. Bush meat is like a gastronomical time travel into the book of my childhood depicting animals of the African continent.

Around the table, with the brother who just joined, they bring a bottle of wine. It is a proper bottle of wine, with a cork, and not the usual carton box everyone drinks. When they see my surprise, they promptly reply: “oh, on est a la chefferie la !“. It is in a good atmosphere that we share stories until I fall asleep.

Once again, our hosts have friends and family in Europe, but these relatives don’t answer phone calls anymore. They stopped answering as soon as they started making a life on the continent of the rich. It is a story I have heard a dozen times. I can’t tell if the African diaspora actually cut links with people at home to avoid the requests for money and presents, or if they are called “friends and family” just because they made it to Europe.

As Paul is Gabonese and his wife Cameroonian, we talk a lot about the differences between the two countries. Mama Sita confirms that food gets even pricier as we will cycle further from the Cameroonian border. There is no dish under 1000 CFA here, when we used to get even fish and meat for 300 elsewhere. She used to live in the South and she prepared meals, that she sold at 1500 while the average was around 3000 (4,5 €). She says people from the city hall came and kick her away for undercutting the locals. As if no one could sell for cheap here. The SMIG (minimum salary) is 150’000 CFA here (225 €), but employers don’t always respect it. Especially the Chinese, who deliberately pay below.

She adds that in Equatorial Guinea, employers respect this minimum salary and it helped eradicating extreme poverty. Even if they belong to the same ethnic group, Equatos are seen as less educated and more “savage” by the Gabonese. The story of the savage country, where the small population became rich after the discovery of oil, sounds a bit like Norway (although I suspect Norwegians to redistribute oil wealth better than Guineans).

They confirm that they can grow anything here, but that elephants and animals come to destroy the crops. By the way, elephants have been spotted at the Lalara roundabout (7 km before Viafe), on the road, just after we left the place! We missed them by a few minutes. In case an elephant attacks a village (and only in this case), villagers are allowed to shoot it. They must call the forestry guards who will collect the ivory and they are allowed to share the meat. Apparently, elephant meat tastes delicious (so does crocodile meat and the flesh of boa). But in practice, animals only come at night to steal and destroy the crops, don’t harm any human, and return in the bush during the day.

In my ongoing research about “are the Gabonese paid to do nothing?”, Mama Sita, from her Cameroonian point of view, adds her word. She says the Gabonese are not travelers. They don’t leave the country as long as they have food and alcohol. And they really don’t like Cameroonians. But as she says, if the Cameroonians were not there in Gabon, the Gabonese would have nothing to eat (apart from their bush meat, of course).

Our last topic is the funniest one: we talk about the oncoming villages on our route. We have earlier made the decision to skip the capital city Libreville, which we could have reached using the shortcut dirt road via Médouneu. Libreville is on the coast and the coast of Gabon has no roads: it’s only swamps. There are no roads along the Atlantic Ocean. Port-Gentil, the second largest city, well known for its offshore oil fields, is only accessible by air and by boat.

We found out that Congo has a consulate in Franceville, in the south, so we actually don’t need to visit Libreville to obtain the next visa. But in order to go to Franceville, we must take the road through the Lopé National Park.

Our hosts say there are very few villages on this road, and we must definitely plan ahead in order not to get stuck at night in the jungle: it is an animal reserve, so elephants, monkeys and panthers could visit us. They talk about a town called Chengué-ville, at the entrance of the Lopé NP, that has everything: fine houses, electricity, antenna for the phone network. It is because a senator lives there. But the place is cursed!

They say the inhabitants, the kotakota, can spell a cast on visitors by hitting a rock. It is called “taper le diable” (“to hit the devil”). We should not to anything wrong there, not eat anything we are offered, and ask for the permission even for a pee or for picking a mango off a tree. If ever the kotakota “tapent le diable” against us, we will die. Chengué-ville is well known and feared all over Gabon and Cameroon, because if you harm someone, this someone can go to the town and ask to “hit the devil” against you. Then you would die. The cast works remotely.

Chengué-ville is maybe the same place we were warned against in Nkolmengoua, during our first evening in Gabon. It was about a cursed village, which can be too hot and too cold during the same day, where nothing grows and where a thick mist envelops the houses. The village is said to be cursed because when the first White missionary arrived there, the villagers ate him.

Mama Sita and her brother also warn me against a second village to avoid. After Ayem until Lope, there are no villages, only two “campements” (hamlets). Under any circumstances, we should not sleep at the second one, as those people “hunt everything. We don’t know what they do with humans …”

That is really a lot of stories for the evening. Mama Sita is smoking local bush meat that she will bring to Cameroon for the year-end festivities.

She shows me the various meats she has on the grill: a basic case of charcoal and a corrugated iron sheet to cover it. She has antilope-cheval (horse antelope), which is “like a horse but as good as pork“, normal antelope (also called “biche”), porcupine and wild boar.

In the morning, they also give me a flag of Gabon to put behind my bike, and we start cycling towards the south, still on the main road.

We are still in the jungle and we see many logging trucks. We also spot many Chinese in 4×4 Toyotas. Locals say they cut the Gabonese logs to export to China.

The river we are now following is the Okano.

The logging trucks often travel in a convoy. There is a Toyota Hillux passing first with a sign reading “ATTENTION GRUMIERS“. It means we’d better stop in a clear area if we don’t want to be hit by a log extending outside of one truck. Even loaded with five or six huge logs on the truck, they take turns without breaking.

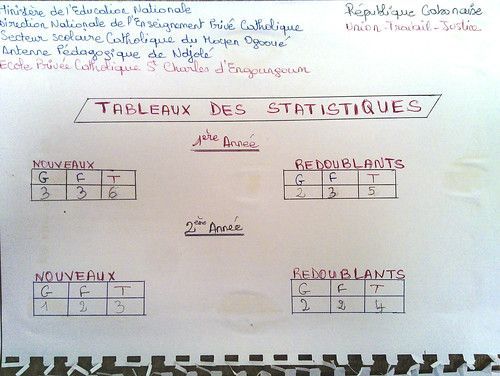

We mark a stop in the village of Engoungoum, where Cyril visits the health center and gets many free medicines (but no diagnostic for his feeling of weakness). The treatment for malaria here is again another one I hadn’t heard about: artesunate amodiaquine, by Sanofi Aventis, with only 6 pills over 3 days.

Small visit on foot inside the jungle, along a path of forestiers:

A question that I am often asked: “So, when will you reach Cape Town?”

We stop after a long ride in the forest where we spot monkeys. We sleep in the school of the villages of Métouang and Mévang. The logging trucks are stopped here as well, because they are not allowed to drive at night. It is a good rule, as their speedy driving is dangerous enough during the day. There are small bars with music and beers, but as usual with food, people don’t know where we can eat. It is like if the Gabonese are only cooking for themselves. We are lucky to find food at one bar, where dishes of gazelle and kassava are served.

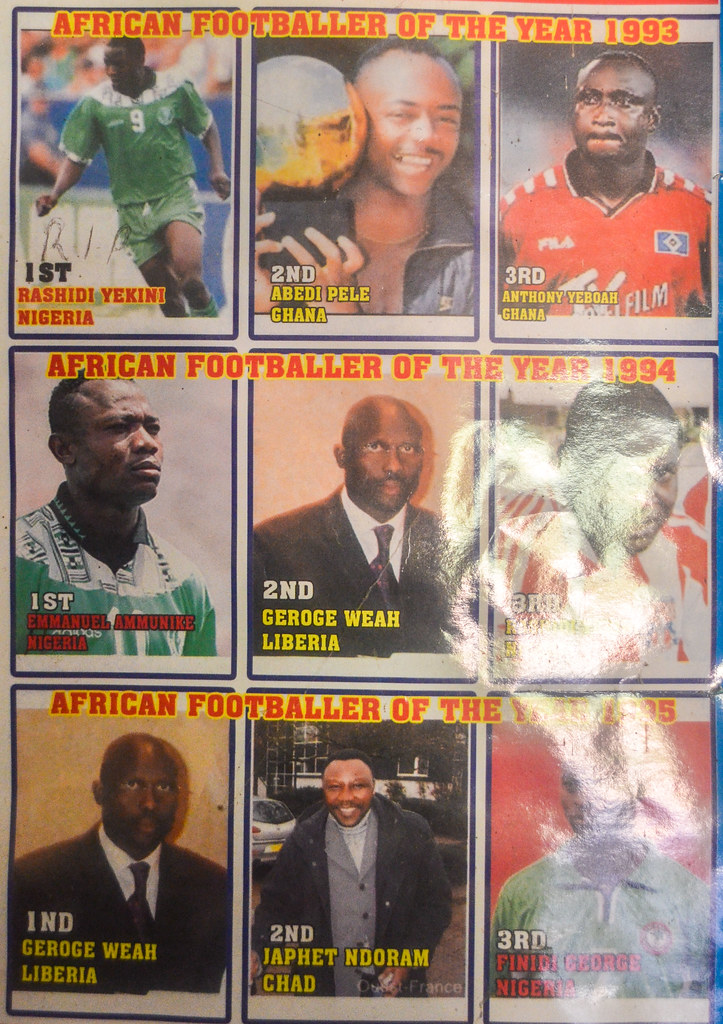

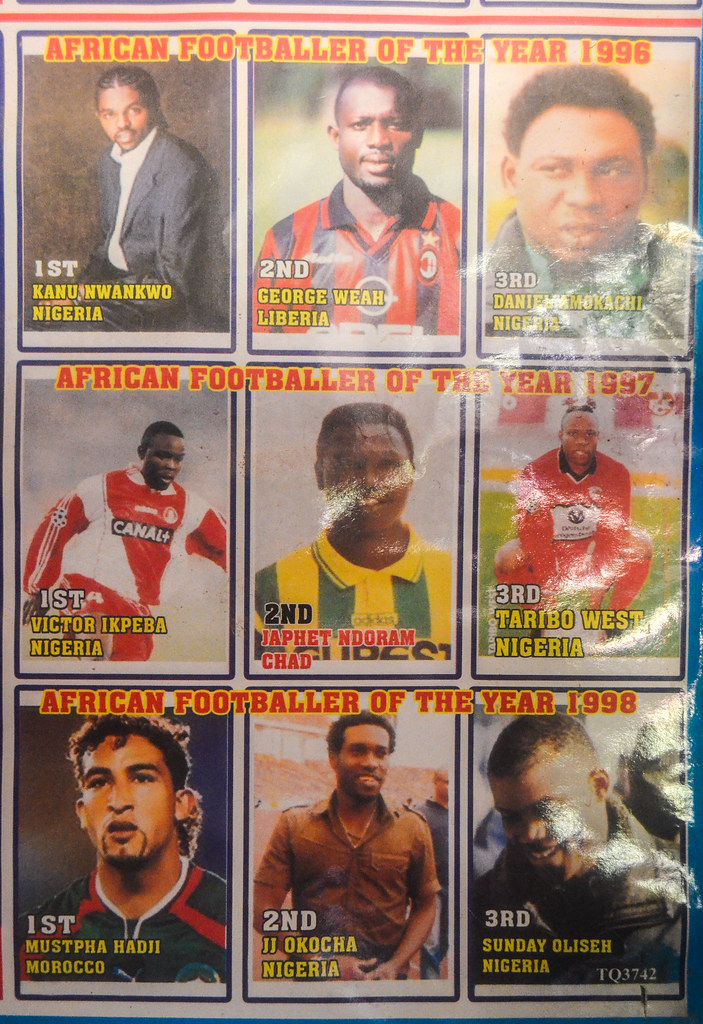

The village of Mévang has a shop run by a Malian. He has posters of the players elected “African footballer of the year” who immerse myself back in time when I knew all the players of the French Division 1: Japhet Ndoram, Victor Ikpeba, George Weah, JJ Okocha, Taribo West, … Nigerians outperform the award.

In the shop of Mévang, we can see billboards for the Airtel phone network, meaning the shop also sells phone credit. But I get no signal. There is not even a single phone network broadcasting here. We have been out of network coverage for two days actually. And we stayed on the main road of Gabon, probably the only paved one.

The network is very poor indeed, and the story behind the Airtel signs is not giving much hope to the Mévang community. There is actually a cell tower behind the shop, but no instruments are installed on it. It is because the cell tower is too short. We can see easily it is not complete. And why is it too short? Because the foundations are not strong enough. And why is it so? Because the contractor kept project funds for himself instead of spending it on the materials. As a result, the cell tower is useless and the contractor is in jail. And there is no phone coverage on more than 100 km of road on the backbone transportation corridor.

From afar, I saw that bush meat stall with a piece hanging: it is a turtle still alive!

As we are approaching the Equator, we meet logging trucks without their load. They carry the mobile rear axle on the top of the truck cabin so as to drive faster.

Finally into the southern hemisphere! It took me more than one year to cross the northern one. But it will be much faster from now on: I did almost 18’000 km until now, and the total distance of the journey will not exceed 25’000 km.

There are no sinks or bathtubs readily available to make the experiment of the whirlpool. I’m happy enough with this sign that I don’t need to ask Coriolis if he wants a proof of his theory.

We reach Otuma village, the “village that has network coverage“. Because the network is so bad, drivers know in which villages of the road they will be able to make a phone call. It is not really practical for emergencies. The signal should appear only in the turn of Otuma 1, or at the hill of Otuma 2. We try at both places, and Libertis only works once, but the signal is too weak (ping over 20’000 ms) to do anything on the internet.

The road around Njolé is very dusty. It is a gravel road under construction. More precisely, it is being enlarged. The road works start just before Alembé with a bridge under construction by DTP terrassement, a subsidiary of Bouygues.

Alembé is disappointing surprise: we thought there would be a town at the crossroads of the two largest roads of the country, the main one going to the capital city Libreville, and the “route économique” going to Franceville, the country’s third city. But there is nothing: three wooden houses only, standing up in the dust, stolen away from the Far West.

The journey onwards will follow the “route économique” (economical road), called this way because it originally goes to the economical capital. Well, in the facts, Port-Gentil, with the oil, is now the economical capital. Franceville had (and still has) a manganese mine, and people keep calling the road the route économique.

Near the hamlet of Alembé, in which we find beers, and luckily rice cooked for the road workers, the mountain is being dug in and poured into the Okano river. This is how it is being straightened and enlarged.

The incessant ballet of the logging trucks is lifting up all the dust.

This steel bridge was constructed by Paindavoine Frères. The French company completed many of those bridges in various Africa countries. It went bankrupt and disappeared in 1965, following the Biafra war that hit their project of the Onitsha bridge over the Niger riger. I guess those bridges are used until they collapse.

Taking the bridge over the Okano river changes everything. We change road from the main one to the second main one, from the RN 1 to the RN 3. The little traffic disappears, as well as the asphalt. The gravel road is very nice, and the atmosphere is … very special. It might be the wildest place, the most untouched place I have visited so far. The only sounds are the sounds of the forests: birds, and possibly monkeys. It is very beautiful, very quiet and very remote.

Our goal is Junkville, and we still have some way to go. Our speed on the gravel road, and especially the hilly profile, will make us arrive late. All of a sudden, the suffocating rainforest disappears and is replaced by grass hills. For no reason. The new landscape looks man-made. Why would there be grass here when the jungle invades even roads?

A forest ranger will explain us later that there is a long tradition or setting fire to the forest and grasslands to attract animals. The tradition is perpetuated today, even within the boundaries of the Lopé national park.

At one point, we meet the Ogooué river. It is the main river of Gabon, 1200 km long and giving its name to 5 of the 9 provinces. It originates in Congo, near the Plateaux Batéké, crosses Gabon from east to west, and pours into the Atlantic ocean in Port-Gentil.

There is a railway across the river and the Otouma station is just on the other side, where we can see buildings. There is a boat crossing over the Ogooué only for the Chinese, French and Lebanese forestiers who work here. The railway brings them directly from Libreville or Njolé.

We finally reach Junkville at night. What a name for a town. Landry, walking around with a wooden leg (timber accident), welcomes us until the house of the chief Daniel, who lets us sleep in the spare room. Landry takes us to bath in a stream. It is much better than a bucket of water! It has been ages I didn’t put my whole body into water.

Junkville is written “Junkville”, but it is in fact pronounced like … Chengué-ville! It is the cursed place!