I am an arinaka (or some name like this), a nomad, in Yoruba. That is my answer to people who don’t understand what I am doing on a bicycle in Africa (and they are many). They ask if I am working in Nigeria, if I am a tourist (but then, why a bicycle?), if I am investigating or making some research. The most likely option is that I am selling things. “What are you selling?“, some people ask when they see my four bags on each side of the bike.

One of the lowest and hardest jobs is the one of the ambulant seller. They have a lot of things to sell (mostly plastic things made in China like torches, belts and toys) that they carry as they can: on an old bicycle, in a wheelbarrow, in a backpack, on their head, in plastic bags… They sometimes walk on the roads between villages and they sweat as much as I do. I am always surprised when I see a young man pushing a huge amount of Chinese crap on bad dirt roads to visit remote villages, and this is what road-watchers maybe think of me when I arrive somewhere with my fully-loaded bicycle.

Once I leave the Olumo rock in Abeokuta, the road to Ibadan is not as congested as I thought. It is linking the two biggest cities of the Ogun state and the Oyo state, but is okay to ride. However, I expected in Nigeria the best roads of Africa and a continuous traffic of brand new 4×4 from all that oil money. The richest African is Nigerian, as well as 11 of the top 40 richest Africans (only South Africans do better, placing 12 in the top 40). It is also said to be “the world’s second-highest growth in new Champagne consumption from 2011-16, trailing only France“. The reality is different from all the good we can hear about Nigeria’s economy: the road is paved but very average, with its potholes, and most of the cars are the usual old ones that must be visiting a mechanic every week. Nigeria is still a country where 63% of the population lives with 1 USD a day.

I like the houses by the road, they are as nice as in Abeokuta, with a colonial feel, instead of the basic square of concrete blocks with an iron sheet on top. But they are mostly in ruins (which doesn’t mean that are vacant).

People are cooking by the roadside, and there is not a single checkpoint on the road. Before Abeokuta, the crazy checkpoint frequency must have been only because of the border area. I feel better away from the cities, where such places, in which I can stop for more than 20 seconds without having someone coming up to me, exist.

The traffic is small but the cars are coming at a very high speed. I reach for the night Ibadan, that could have been West Africa’s widest city a hundred years ago. It is today the third largest Nigerian city, after Lagos and Kano, with over 3 million inhabitants. It is not possible to avoid it as it lays at a major crossroads.

It takes time between the moment I enter the urbanization and the moment I see the proper center, and a high building! It feels like I have not seen a building over 20 stories in ages. The navigation inside the city is hectic as usual, but I am more confident and I compete with the okadas: I have the same size and can start up as fast as them, when the traffic leaves a bit of space to move forward. I spiral between cars and get into tiny spaces. The lanes are wide, the roundabouts jammed and there is even a bypass highway over my head. But it works fine until I reach the first hotel I see on my Google Maps.

They don’t have the cheap 100 € rooms available anymore, so I can only book the presidential suite for 200 €. The reason I went there was because it looked cheap, a simple house in a guarded compound. Okay … everyone knows Africa is expensive for travelers compared to Asia for example, but some prices are just ridiculous.

I am finally redirected to a “safe” guesthouse for 30 €. The general consensus is that “safe” places start at 5000 naira (23 €). Even there, there is no electricity during the day. The public electricity is provided by NEPA, but as the guesthouse manager tells me, it never really worked since the independence in 1960. It “comes” about once a week in the neighborhood. Electricity is never part of the basic package of life below the Sahara, I am surprised it doesn’t even work in Ibadan, the 3rd largest city, in Africa’s third biggest GDP, and next to the governor’s house. As a result, houses (that can afford it) must have a generator they run from sunset to sunrise. Another consequence is that there is no or very little public lighting, which makes him recommend me to avoid the streets after sunset, as they are safe for no one. I met some nice people during my brief stops during the day, so it is disappointing to have to stay locked indoors from 6 pm until 7 am the next morning. But if it is the general guideline … Fortunately this place is a restaurant too so stomach is safe too.

As usual, there is a TV with satellite (but the channels barely work) and no wifi. As I have been told, Africans won’t stay in a hotel if there is no TV, while Westerners will look in priority for a wifi connection (provided there is choice and funds available).

During a chat with the cook, he describes Nigeria’s population like I have read about it: very (very) roughly, the south west is home to the Yoruba people, the educated and forever corrupt, who run almost everything. The south east is where the Igbo people live, they have oil in the Delta, but the money goes mostly in the pockets of the Yoruba, and the Igbo area remains underdeveloped, so they kidnap foreign oil workers to make their point (since the Biafran war didn’t yield an independent country). And the north belongs to the Hausa people, is Muslim and famous nowadays for the massacres of Boko Haram. The whole makes a single country inherited from a British colony, that could easily be 3 independent states, since there are far more differences between those 3 groups of people than between Spaniards, Italians and French for example (and there are actually hundreds of groups, not only 3).

Among other conversation topics, he coined the expression “African continent: God’s spoilt child“, to illustrate that everything (food, rain, resources) comes so generously and so easily in the continent that no one has been making efforts to develop. He also tells me that the “famous” White farmers from Zimbabwe, that had been somehow forced out of the country by Mugabe in 2000, were given plots of land in a Nigerian state, and the results are good. And also that one state governor just acquired an armored car for 1 billion euros, while some ministries are not able to pay the public servants because of “lack of funds”.

It takes me more time to get out of Ibadan than to enter it. I spend my 20 first kilometers of the morning in the eastern part of the city. I also miss the correct branch of a giant roundabout and end up on a highway instead of another. In the roundabouts, like in the traffic, the trucks are my friends: they are so slow and it takes them ages to start up after being stopped that they create gaps in the lanes, allowing me to move easier (as long as I get far from the truck quickly enough). But when on the highway, the trucks are supernatural forces: they speed and honk constantly like if they don’t have brakes (well, maybe they really don’t). As they don’t brake, every car must move out of their way, pushing away the motorbikers, which in turn push me out of the way. On the highway, I see workers cleaning the roadside, bent over the asphalt behind red cones, with straw broom, the common ones without a handle.

The calling for White people in Yoruba is “Oyihbo!“. I have already heard this one a thousand times and it won’t stop soon. I am also called Boko Haram, I guess it is the local version of the people who would call me Osama elsewhere.

On one rice stop along the road, I order my plate in currency, as usual:

“- How much rice you want?

– Thirty

– Seventy naira?

– Thirty

– Seventy?

– Thirty naira! A 3 and a 0.

– Ah, saaty naira”.

It takes a bit to get used to Nigerian English (“cycling for one yhé? You’re weahcome!“) just like it took with Liberian English. I keep seeing abandoned petrol stations along the road. There is one at least every 5 km reclaimed by nature. It also looks like every petrol station is of its own brand. The liter of petrol in stations still working seems to be fixed at N 97 (0,45 €).

From Iwo until Oshogbo, each of Google Maps and OpenStreetMaps display a different road. I don’t pay attention and keep going straight on the main road, as I am already on the main road Ibadan-Oshogbo. But it turns to be a very quiet road and rather narrow …

A police car overtakes me and its loudspeaker is calling for me “WHITE MAN … PARK. WHITE MAN …. PARK“. They are just curious to know about me and the usual chat goes on (“So how long ago did you leave? Whoaa! And with this same bike? Whoaa! Etc …“) until I can axe them about this road. It is in fact the old Iwo-Oshogbo road, too narrow and too destroyed for the current traffic, so all the cars are on the other road.

They confirm to me that it is safe, as it is my main worry to be alone without any car, but I quickly forget about it and enjoy the scenery. After all, this is the first time I am alone on the road and I can unglue my eyes from my rear mirror. By the way, this bar-end rear mirror is a life-saver. It must have saved my life several times since I left, just like the mosquito net I bought in Nouakchott. Cheap hotels don’t have mosquito nets and better ones think a fan or A/C get rid of them (it is not true).

I really enjoy those kilometers of straight road, going up and down in the greenery, with a road so badly destroyed that only motorbikers and I can take it. Nigeria finally feels the side of Africa I like, with deserted bad roads or laterite pistes taking me in the nature of remote places.

It doesn’t last forever and I have to return to the hectic traffic when I get close to Oshogbo, another big Nigerian city in the top 20. Most of the population in Nigeria, hence most of the large cities, are in the south. I headed to Oshogbo on the recommendation of CyclingCindy to visit the Osun sacred groove.

There is a motorbiker, and even one car, that made a U-turn after passing me, just to see me again and to axe me to stop. I don’t know their motive so I keep cycling. They are either 1) over friendly and want to know more about me, or 2) very stupid and want to follow me just for fun and maybe engage into a conversion while driving, or again 3) bad boys potentially dangerous. Even if they are most likely from the two first category, I can’t help thinking about the third.

Finally, I am now getting better at the routine – find hotel – fetch food – stay inside from sunset. Everything works according to plan for this evening.

In the morning, I visit the Osun sacred groove in the south of Oshogbo. Osun is the name of the state and of the river that passes through the sacred forest, and also of the deity praised there. This is one of the major sights of Nigeria, maybe the most prominent tourist attraction, and it reveals how underdeveloped tourism is. The entrance gate is very quiet and I am the only visitor. The only art seller there, Patrick, confesses that I am the first tourist (the first real one, without 4×4 and armed protection) he sees since he returned to Nigeria one year ago, and he had been standing at the sacred forest for 2 months already.

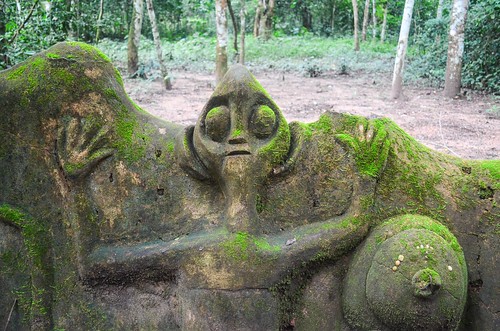

The sacred forest contains a shrine where the locals can go, or bath in the sacred river, and make offerings (which results in dead chickens floating on the river shore). What makes the place special is the presence of sculptures everywhere, in harmony with the forest. An Austrian artist, Suzanne Wenger, lived there for most of her life and her artwork, related to the Yoruba deities, transforms the forest into an open air museum.

The god of chicken pox is to be worshiped in case you axed something to the gods, received the something you wanted, forgot to make an offering to thank them, and got cursed in return. He apologizes to the gods for you.

I leave a noon time on the way to Ilesha. The road is rather quiet and it is a good surprise.

After Ilesha, the road joins the main highway that I had avoided from Ibadan. There are now too many trucks and cars at high speed. It is mostly jungle, with branches falling on the road, and a few villages, but I can’t relax: I must jump aside from the road, on the dirty lane next to the grass, where pebbles, branches, trash, potholes, etc, pile up. I cannot stay on the road for more than a minute, as the cars overtaking each other don’t care about me. The worse is when the cars coming in front of me are overtaking each other: they end up on my lane, speeding right into me. What else can I do apart from jumping on the roadside? It is “normal” that no attention is given to a bicycle since the law of the biggest vehicle prevails, but I have never felt more invisible.

I stop in the small town of Ipetu-Ijesa, as I have seen a nice hotel sign from the road. I have enough time to check-in and take a walk outside to meet the curious people, greeting peacefully without the crowd that I usually attract in a big town.

I witness one light accident (a car driving into a shop) and bump into an immigration officer. I have no clue what he is doing in such a small place, but his badge seems real. Apparently, there are Chinese workers around. It is probably mining or construction. He says he must control me because Nigeria is so easy to enter. How come so easy, I struggled to get my visa! But he adds that you just need to give bribes at the checkpoints and you can get in, and this works with every officer (but not him, because he is “not like them”). So maybe that is why there are 5 immigration posts in a row at the border: if one really wants to enter, he needs enough money to dash every one, and in the most prevalent case of a poor African migrant, he cannot afford it. That is the corruption fortress that protects itself from uninteresting foreigners (and yes, this is all within the ECOWAS treaty for free move of goods and people in West Africa).

It reminds me of a story I heard on the road, but I don’t know how true it is. During the oil boom in the 60s and 70s, Nigeria attracted many workers, not only the western companies, but also the West Africans always ready to move to greener pastures to work and send money home. In the 80s, the oil crash made the country situation very bad and the government decided to get rid of all those illegal immigrant workers (3 million people). Without any immigration control, their efficient solution became “Get out of Nigeria by this date, if we catch you afterwards and you’re not from here, we kill you”. Of course it worked well, but it made it terrible for the workers to return home: they had to pay on their way back as may bribes at each checkpoint as they had paid to come in. Except that now, they had no more money and were under the pressure of the ultimatum on their life.

To come back to the “god guy” immigration officer of Ipetu-Ijesa, no later than 1 minute after he claimed to be anti-corruption, he axes what do I have for him. Pathetic …

About corruption on another level, the one that seems to be main responsible for Africa’s visible poverty, the LP says: “In 2005, the government’s anti-corruption commission announced that over US$352 billion had been stolen or misused since the oil came on tap: four times the value of all western aid given to the whole of Africa in the last 40 years.”

It has been now 3 nights in a row with strong rain, but nothing yet during the day. I check the news on the internet about the events of the week in Nigeria: 2 Americans kidnapped on a boat in the Gulf of Guinea, and killings in the north by Boko Haram (and by the army killing them in turn). It is really not the place to be cycling in. But maybe the truth is what everyone says, “Nigeria is super safe, just don’t go to the north” …

This is amazing, please keep this up

that good trip, you are a very special person , must be made of good wood to travel so long, and these countries. I travel often ,midle orient asia , latin america and africa is my passion , and my dream is to travel to Nigeria as you visited , also Burkina Faso and Mali , to see if things are a little better in a few years , I I live in Gran Canaria and I have a few hours of plane, Senegal and Mauritania and Guinea , a big hello friend for you and good ideas, and ways of living so vivid greetings Pablo Gallego nicoletti

I must say, this is an awesome thing to do. My family is from Osun State: Ipetu Ijesha and its nice to see it represented in your series. Interestingly, I had no idea that such beautiful sculptures are in the Osun Oshogbo Grove. It is now on my list of places to visit…thank you. Safe travels and although I don’t know you, but I think you are awesome for doing this.

Thanks Kemi! Enjoy the sacred grove, it’s is quite unique and you can walk freely in there.

Wondering why you are describing that people are “axing” instead of “asking”?

Sounds like a dangerous place indeed 😉

Hugs,

M

It’s what I hear on the roads, many anglophones say axe instead of ask. I also heard mox for mosque. It doesn’t sound cool?