How does a plate of beans with flour on top sound for breakfast? It is strange but good for a change. The morning is rainy again. I head north so as to see a bit more of Togo than what I could do: from West to East, from Kpalimé to Tohun, the distance would barely be over 100 km to cross the country.

The West of Togo is the mountainous region and I take the road along the hills.

I make a stop shortly after to take a morning wash in the Kpimé waterfall.

“Un petit cadeau? Il faut me donner un petit cadeau” is what I hear the most from the kids. This day is not very motivating: the cloudy sky is hiding the mountains, the road is completely destroyed, and the rains falls every now and then.

Google Maps is completely wrong for Togo. Completely unusable. The destroyed road I am on is the main road between Kpalimé and Atakpamé, the 4th and 5th largest cities of Togo.

I prefer by far a good unpaved piste to a destroyed asphalted road. This one is being rebuilt, on a small segment only, by the Chinese. Maybe I will stop mentioning it, as I have seen no one but the Chinese building those much needed roads. The houses nearby are also taken down, I guess they are too close to the future wider road. It looks like a war just happened. I stop for a reinvigorating drink to decide if I should wait the current light rain to stop or if I should go before it gets stronger.

Youki is the local alternative to Coca-Cola and other Sprite. It is the same price though. I have been now in enough countries of West Africa to notice that the breweries and bottling factories are quite similar with the same products. Here in Togo, the bottling is made by SOBEBRA (Société Béninoise de Brasseries). Earlier, it was SOLIBRA (Ivory Coast). Even earlier, it was SOBRAGUI (Guinea), SOBOA (Senegal). Apparently, it goes on the same way in Cameroon, Gabon, DR Congo … and all those companies are part of the same group, BGI.

They all produce the same beers that one can’t miss in any francophone country of Africa: Castel and Flag. The same breweries also bottle under license Guiness, 33 Export, and I guess even more products. It seems they have a monopoly in each country. The parent company is the Castel group, the 8th richest French family, which also produces (a lot of) wine. Castel is number 2 in Africa, behind the South African SABMiller, the world’s second largest brewer (but the downside is that they brew Castle, Peroni and Grolsch …). Castel and SABMiller have signed an agreement to share African markets together. It sounds like any drink in a glass bottle I will have is bottled either by Castel in a francophone country or by SABMiller in an anglophone country.

The mountains are not that high, but they are covered by the mist. With that bad road seriously slowing me down, I quit the idea to make it to Atakpamé today.

The rains falls stronger, obviously while I am cycling a stretch without any shelter. Once drenched, I decide to cycle until the first village with warm food on the side, and this is Amlamé. I only had 200 CFA of rice so far for the whole day, and this tiny food intake is abnormal.

I have fried yam, the local thing closest to french fries, with spaghetti on top, because spaghetti are just fancy stuff served on the top of anything. The people tell me that the road is destroyed by the Chinese trucks that carry material to build that same road closer to Kpalimé. But they don’t know if they will repair it. Well, from the 2009 news I found dealing with the kick-off of the Kpalimé-Atakpamé road works, and considering there is less than 20% suitable in 2013, the people of Amlamé won’t see a nice road any time soon.

I realize the food stalls and the shop are all managed by brothers, and the father Jean invites me to his house when I just asked for a guesthouse to be in a dry place. Jean’s house is huge. It needs to be, in order to fit 5 wifes and 17 persons in total … But his son Augustin makes me move to the neighboring huge house, from his uncle working in Lomé, where I have a spare room. Washed and dry for sleep, that is the best thing I could hope for.

After a breakfast of pâte, the Togolese version of the banku of Ghana, and a visit of Pipo’s project, the most popular rastaman of the region, I head for the last bits of tough road until Atakpamé.

“Africans wants money and food before they start to work. How can one work with an empty belly? Rastas put efforts and work first, knowing it will result in money and food later“, was saying Pipo, explaining why Rastas are seen negatively in Africa, while they are far from belonging to the laziest.

Atakpamé is nested in the hills. As I get closer to the city, I see it in detail on my GPS, but still nothing in front of me. This main road can’t be climbing over this hill, can it? And yes, Atakpamé is uphill (from Kpalimé).

I find more variety than in Ghana concerning snacks on the roadside. I stop for snacks at the entrance of the town, with soja, tasting good like a fried tofu, and akma, a paste of maize that has really no taste.

I stop a second time for lunch, pâte again, with meat. I choose myself the meat pieces in the big pot: there are for 50 CFA, bigger ones for 100 CFA, and the pieces with actual meat for 200 CFA. In the end, my beef plate is made of things that I would never find in a T-bone steak plate: the oesophagus, the skin, offal and tripes.

Atakpamé marks the midpoint of my Togo crossing and I continue eastbound on a dirt road to the Nangbeto dam. This road should continue further on to Bénin, but it is far from being the most obvious option.

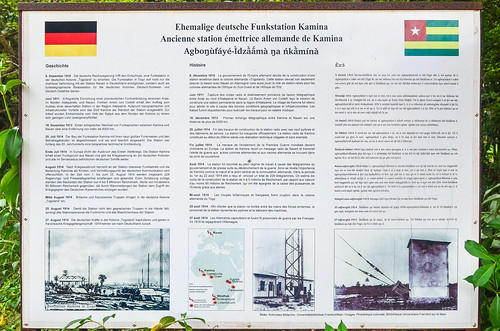

This exploration rewards me with a surprise: a few kilometers after Atakpamé, I am stopped by an information sign on the side of the road. An information sign is very rare. This one says the location, Kamina, was home to a German radio station.

That is the opportunity to learn about the little known German colonial empire. Within Africa, Germany occupied Namibia, mainland Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi, Cameroon, and Togo. Until WWI, Togo was called Togoland, and the German government decided in 1910 to build a radio station in Kamina to link Germany with its colonies in Eastern and Southern Africa. The works ended in July 1914 and Kamina was a technical achievement for that time. But “unfortunately”, WWI broke out and the British and French armies entered Togo in August. To prevent their enemies to use the radio station, the German dynamited it.

It is a shame to destroy a transmitting station only 2 months (and 229 messages transmitted) after its completion, but the sign says that the alerts given through Kamina allowed to save 50 million reichsmarks of German assets, to be compared to the cost of 4-5 million reichsmarks for the station construction. And it also means there are my favourite, ruins, to explore around.

After Togoland was “freed” from the German occupation in 1914 by the British and the French, it was shared in 1916 into British Togoland (the westernmost third, just east of the Volta lake) and French Togoland (the easternmost two thirds). The British Togoland merged with Ghana while the French Togoland became the present Togo. This explains why the language remained the same when I crossed from the Volta region of Ghana to Togo, it is the same Ewe people.

I don’t see much ruins around this sign. The area is just covered with maize plantations. I only notice huge concrete pillars that served as anchor points for the cables maintaining the antennas.

This is until I am spotted by the children. “We will show you the antennas“, they scream, and I happen to be led by 15 apprentice guides. Well, they are guides that point at anything and say “this is an antenna“, but they took me to places hard to find within the maize plantation, because the villagers are using the whole area of the old Kamina station for agriculture.

It is quite surprising to see German remains from WWI in Africa and kids playing around, while their parents grow maize. Their favorite is to show me the tunnels, that once upon a time linked this part (I presume the antennas and transmitting office) to the house, some 200 meters further. They say that the French blocked the tunnels and now the network is limited to 20 meters underground.

My favorite was when I found on the internet a copy of the Telefunken-Zeitung from 1919 which features the Kamina station. It has pictures of the very same location under German occupation with the installation working. The turbines on the photo below are the same turbines that I climbed onto with the kids, 99 years later.

The last item they have to show me is a mysterious storage room. It looks like an underground bunker sealed with concrete and a huge steel padlock. “What’s inside? Can we open?“, I ask. “No, only the Germans can open it. The French tried it but they couldn’t. There is equipment, bombs and money inside!“. It is strange that no one opened this intriguing chamber, but maybe it was tried on in 1914 with small tools, and then forgotten.

Near the old Kamina house by the road, I chat with the group of people idling there. There is a teenager selling tchouk, a drink made of fermented mil served in calabash bowls. It is like a traditional beer, for 100 CFA a big bowl. There is a non-fermented version of the mil for children. I ask the adults once again what is hidden in the underground storage room that no one can open. The answer “We can’t tell, but we will know in 2015 when the Germans come back” was a bit scary at first, but they actually mean that Togo and Germany signed a cooperation agreement starting soon.

Togo has been under German protectorate from 1884 to 1914 and under the French from 1914 to 1960. From the little I can feel, the people have a better image of the Germans. They had apparently built railways and more things than the French did. I have crossed those railways, in the town of Atakpamé, abandoned, like most of them in the region.

I continue my road towards Nangbeto that I had targeted to reach for the night. The long unexpected stop in Kamina makes me hurry a bit. The piste is nice and the asphalt comes back in Akparé.

I reach the Nangbeto dam at night. It is pitch dark at 6 pm now. In Benin, just a few kilometers further on the east, I will change time zone and “win” an hour in the evening. All the shops in the town and the villages have put stalls in the streets to sell textbooks and school bags. The start of the school year is soon, on October 7th.

Nangbeto is a dam city: the Germans built it in 1987 over the Mono river as well as a cité for workers, with a hotel I have been directed to. The hotel is a nice one with A/C rooms for 12 000 CFA, four times my hotel price and twice my hotel maximum price.

When I ask the security if I can crash or camp around instead, they take me to their leader, Mister Kao. He is the boss of the 27 security guards around the dam and the cité, in cooperation with the gendarmerie and the army. A dam is really something sensitive here. I can’t help thinking about all the dams in France, Germany or Switzerland where you can walk everywhere without seeing anyome working on it.

Mister Kao takes me away from the Nangbeto cité, which hosts the people working for the dam, to the compound of the security people. They have houses and huge hangars of iron sheets that look like airplane hangars. Apparently, it was built as temporary buildings by the Germans during the dam construction to host equipment and workers. They wanted to take them down once the dam completed, but the locals have asked to keep the structures.

This is how I ended up with a “room” in the hangar, where I can put my bicycle and air mattress. We dine together pâte again, which means I have had mashed kassava for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Great.

The salary for a security guard is around 20’000 CFA, 30 EUR a month. This is why most of them are also using the land around to grow maize and kassava, and work in the fields when they don’t work for the security.

The sky is super clear but I am lost. All the constellations I have learnt in the Sahara desert are not there anymore. Not a single of them. It takes me a while to recognize the sky with an app on my phone.

Around my camp for a night:

The Nangbeto dam built on the Mono river has a power output of 64 MW (2 x 32MW). It is owned by Togo and Benin together. The commemorative stone mentions the two presidents in 1988, Eyadéma, at the head of Togo for 38 years (the current president is now his son)(the minimum age to be president had been lowered to 35 years just before the father’s death) and Kérékou, who presided Benin for 27 years. The beauty of “controversial” elections …

The asphalt stops just after the dam. It is followed by a good piste until it turns to sand. The sign reassures me that Benin is this way, even if I don’t know where exactly will the border be.

I reach a rather big village called Kpeklémé, a crossroads of big roads that I didn’t expect there. My maps are helpless, Google Maps is wrong as usual in Togo, and the good OpenStreetMap is not exhaustive. Landing in this big village feels like discovering something secret …

For me, the border post is still a long way south, along the vertical border with Benin, in Tohun. One local to whom I ask replies that the border is just 2 km ahead … weird.

I ask other people, and now they tell me that there are 3 border crossings nearby. Even weirder …

I take the track going south anyway. If there is a border post, it will be just on my left

The road is very bad and consequently empty. It is at some point washed away by the rain, and I wonder how would cars pass here. Just after the motorbike, I am convinced the bicycle is the second easiest way to discover Africa.

At the Soligbé roundabout, the road splits in two ways: on the right with a sign for Tohun, the official border post on my Michelin map, but which should be straight ahead, and another road straight, where people tell me the border crossing is.

I tried this border crossing close by. People tell me there are border posts ahead for the immigration. I am venturing on this small path, but no sign of any change.

I reach a village and ask where the immigration is. No one knows. “Is there at least a police here?“. “No, you have to go to Abomey“, a motorbiker replies. Abomey is indeed my next destination ahead in Benin, but I would need to exit Togo properly first and I am not sure about how will I be welcomed in Abomey.

There is a road straight to Abomey in 30 km. Unfortunately, I don’t take the risk and return to Togo to pass the border at the official crossing, with immigration and stamps. That makes 80 km instead of the straight 30 km, but also less risks to be annoyed by the police somewhere further.

So for those who want a visa-free border crossing between Togo and Benin, the secret path is between Soligbé and Atomey (7.2280,1.6385).

I continue to Tohun on the sandy piste. It is very hot. When I arrive tired and drenched by my own sweat in villages, some locals resting in the shades of trees ask me to buy them drinks. This is normal.

Once finally in Tohun, the town 2 kilometers before the official border post, I stop at a roadside barbecue to get some meat snacks and decide whether I should sleep in Tohun, or cross the border tonight. I can’t really make a decision as François, the brother of the barbecue man, invites me to his house for the night. It is not really his house, but rather a room with a shared shower, that he rents for 2000 CFA (3 € / month) for when he’s not in Lomé. The language here is no more Ewe, but Adja.

François’s job is about drilling holes for water pumps. He says he makes good money, but he works at a depth of 30 meters without a helmet. By the way, I didn’t see any pump in Togo, hand or foot pump. It had public taps everywhere, even elevated ones, making it much easier for ladies to carry buckets of water. They just have to stand under the elevated tap with the bucket already on the head, so they don’t have to lift it from the ground to their head.

After the shower, he wants to show me Tohun. This is not really possible due to a power cut, the whole town is turned into darkness. The only place lit up is the central roundabout where the ladies gather to make their food stalls, lit by hundreds of candles. It reminds me of a Japanese festival. I try a bit of everything and have the bad surprise with kom, which is a pâte of maize only: it is just like the Ghanaian kenky. At least I will be fresh tomorrow for the next country already, Benin.

All in all, even if this is a short trip in the country, those three days have been great and the people very friendly, making me build a very positive image of Togo.

Guten Tag.

Ihre Beitraege habe ich sehr behilflich gefunden. Ich schreibe gerade einen Aufsatz ueber die Kolonialzeit Togos und dabei ist mir ihre Annahme dass “….the People have a better image of the Germans” aufgefallen. ich stimme Ihnen zu und will deshalb deine Arbeit in meinem Aufsatz zitieren. Wenn es ihnen nichts ausmacht, mir Ihren Name und das datum der veroeffentlchung der Beitrage zu schreiben, werde ich mich darueber sehr freuen. Selbstverstandlich, zitiere ich Sie damit richtig.

Danke im Voraus

Ike Chukwuemeka