How to leave a big city like Accra quickly and smoothly? It is not easy with a bicycle. I could take the smallest roads to avoid the traffic, but it would take me a good part of the day to struggle with the potholes, mud tracks, detours, etc, to get out of the urbanized area.

I choose to cycle on the motorway, incredibly quicker, but also incredibly less comfortable. As the traffic picks up from 6 am, I am out at 5:30 Saturday morning with the first light of the day. There are already crazy tro-tros, the bush taxis, driving like if they have a holy immunity to accidents.

I am not going until Tema since my objective for the day is the Akosombo dam, one of the greatest engineering achievement of Africa. After only 30 minutes, I am on the road heading north and find with surprise a cycling track. A cycling track in Africa? Ghana is definitely special in the region. It is as surprising as seeing one in Errachidia in the Moroccan desert.

I have little reason to stop on the way and achieve 100 kilometers even before 12. This is the first time it happens, and I am glad that I will not need to wait until tomorrow to visit the dam.

The Akosombo dam is almost on the way to the Eastern region, by the lake Volta. The lake Volta is crossed by the Greenwich meridian, which means that after a long way aside from the Zürich-Cape Town direct line (17° W for Dakar), I am almost back “under” the European continent.

The size of the reservoir is huge: Lake Volta covers more than 8500 square kilometers, making it the world’s largest man-made lake by surface area. When the dam was completed in 1965 over the Volta river, the lake flooded 3.6% of the land area of Ghana. It is like if we decide to build a dam in France that would flood the entire Franche-Comté region (and a bit of Alsace). Akosombo displaced 80 000 people.

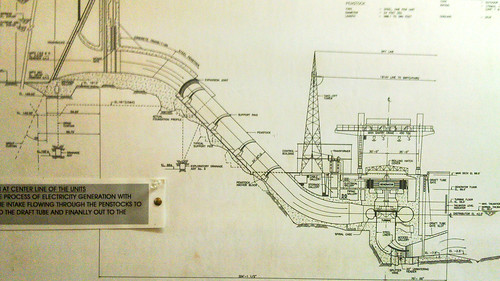

The dam itself has an output of 1040 MW (6 x 170 MW). The visit of the turbines is not allowed for tourists showing up at the dam, so I can only walk on it. Like many of the big structures in Africa, it is a restricted sensitive area (i.e. no pictures allowed), so one has to take an official guide. They stop their activities earlier today and I am just in time for the last tour.

To my surprise, the guide lets me take pictures discretely. “Do it quickly before those cameras catch us“.

There are fishermen allowed to fish just below the dam, right where the water pops out of the turbines. Fishing is a big word, as they just lay their nets to catch the dead fishes that went through the turbines.

Before visiting the dam, I was seeing it as a great achievement of Nkrumah, the first Ghanaian president, that brought electricity to its population. Ghana is even exporting electricity to its neighbors, Benin, Ivory Coast, Nigeria. The truth is that the dam exists because of the presence of an aluminium smelting plant nearby. The British had planned it before independence in 1957. The south of Ghana is filled with bauxite, and to convert it into aluminium, a smelting plant needs a lot of electricity, often its own power plant.

The American company Valco lent money to the project to make it happen, and in return, it would benefit a special access to the dam production. “Initially 20% of Akosombo Dam’s electric output (serving 70% of national demand) was provided to Ghanaians in the form of electricity, the remaining 80% was generated for the American-owned Volta Aluminium Company (VALCO). The Ghana Government was compelled, by contract, to pay for over 50% of the cost of Akosombo’s construction, but the country was allowed only 20% of the power generated.” Today, the Akosombo dam represents more than half of the electricity production of Ghana.

The very good deal for the aluminium company ended in the early 2000’s with a renegotiation of the contract, and it was eventually sold to the Ghanaian government. All of the issues with the displacement of the people and the development of the region are in the hands of the Volta River Authority (VRA), a governmental organization. Some villages around the lake Volta are still deprived of electricity.

The visit of the dam was a bit disappointing. One learns much more by reading elsewhere than by listening to the people of VRA. Downstream, the landscape around the quiet Volta river is very nice.

Because it is not late yet, even after cycling 100 km and taking a tour on the Akosombo dam, I continue my route towards the Eastern region (Ho, Hohoe) in hope to see some mountains.

I pick the straightest road from Juapong to Ho, which is not the one for cars: there is a lot of sand and rocks and I am much slower. It is pretty bad for Ghana. I realize I am entering the Ewe country with the kids shout “yevu yevu!” instead of the “obroni!” in Twi.

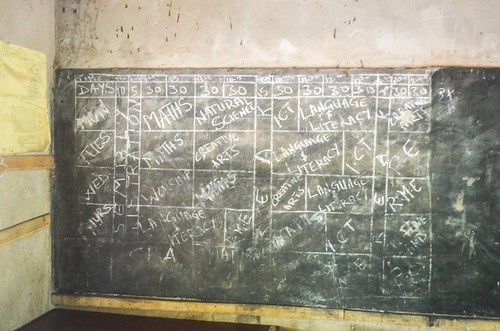

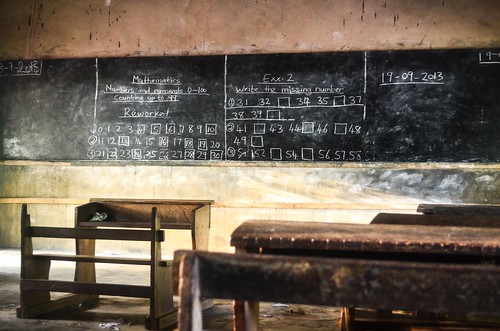

The rain drenches me just after after 5pm. I cycle quickly until the first shelter but my clothes are already soaked. This first shelter is a school compound with three large buildings.

The night comes when it is still raining and I have not talked to anyone yet. I set up my mosquito net in the silence and darkness.

I wake up in the school. On a Sunday morning at 6 am, of a 3-day weekend, the villagers pass by me, carrying tools to go to the fields. I take a photo tour during the sunrise minutes.

The sun at 7 am is already scorching. The road is still as bad as yesterday, with sand, mud and stones.

It seems there are more churches in Ghana than bars or restaurants. On Sunday mornings, it is a national ceremony. I see a boy jumping on a rope to ring a bell. All the people are well dressed, walking on the roads of the villages to their church. Some of the churches are made of bricks with concrete halls, others are just bamboo shacks. Songs are almost everywhere, but I see a wide disparity inside the churches: sometimes a pastor makes a speech at the mic with the audience peacefully listening, and sometimes the church looks like a night-club at daytime.

After the town of Ho, which marks the beginning of the hilly Eastern region of Ghaha, the landscape becomes very nice. The road looks renewed, and the very steep uphill to leave Ho takes me to a suite of very scenic rides.

Yet, it is too hot and I am constantly dripping sweat from everywhere.

There are severe slopes forcing me to push my bike uphill. The road is very broad and new, yet lonely. It feels strange pushing there. I reach Vine, from where I make a detour to Amedzofe, a village on the top of a hill.

I plan to get up to Amedzofe to spend the night, and go down on the other side tomorrow if it is possible. I read that there is no road to go down on the other side but hikers can do it. I hope a loaded bicycle can make its way through as well …

There is much pushing uphill but it is rewarding. The village is exactly on the top of the mountain range. It is not that high (600m – 800m), but since it has been such a long time I didn’t go where one can have a fantastic view of the surroundings, I didn’t realize I was missing it. West Africa is not famous for its mountains so you have to look for it.

I now end up, at 600 m high, higher than I have ever been since the Fouta Djalon in Guinea. I can watch villages far away and see how the roads connect them to each other. I can see until the Lake Volta in the background, below the dark blue tapestry of the threatening sky. It does feel good to be out of the flat roads.

The small village of Amedzofe, called the highest inhabitable place in Ghana, is relatively chilly. It has a small visitor’s centre which charges visitors for walking on the hill or until the waterfall, but overall, the paths are very well maintained and the kids and villagers not begging. It seems they are controlling the venues of foreigners to make a pleasant experience for both sides.

It is 4 pm and I can only think of washing my soaked-in-sweat skin and clothes in the Ote waterfall, a 45 minutes walk from Amedzofe. But just when I am shown the start of the trail, those dark blue clouds explode over us.

By the time the strong rain stops, it is getting late and I decide to make a quick jump on Mt Gemi instead.

GEMI in Mount Gemi actually stands for German Evangelical Missionary’s Institute. The Germans built a cross on the top of the mountain. This part of Ghana was earlier called British Togoland, formerly part of the German Togoland until World War I and merged with Ghana (against the will of the Ewe people) at the independence in 1957. However I don’t know how old is this cross, that is said to have been used by the Germans as an antenna in the past.

I stay at the governmental guesthouse, which has regulated prices. It is indeed not costing that much, and I get a huge room with 2 large beds just for me. The building looks like a colonial hill station residence. However, there is no running water (broken things remain broken until someone really needs it)(and no one really needs a flushing toilet or a shower when there are buckets and a well nearby) and no electricity (the bad rain broke something 4 days ago). It is surprising as Ghana has relatively few “… This is Africa“-moments.

The tricky decision I have to make is about reaching Togo. My next country is just behind this hill. At first, Togo is the country that says “Ah, finally a country where I can get the visa at the border!“. But then, it appeared that not all border posts do this “visa on arrival” procedure. I am in a mountainous region with many small roads going into Togo, and I have no clue which one has border posts and which one doesn’t. And if it does, can I still get the visa there?

The information on the internet is not helpful either. I only found that another cyclist, the famous Peter Gostelow, got stuck around the same place 3 years ago when the Togolese officials refused his entry. This visa-on-arrival becomes now more of a risk than a comfort: my fate will be in the hands of a single officer in the middle of the bush, and he can do whatever he wants. Plus, since my Ghanaian visa is for a single entry, what happens if I exit Ghana and can’t enter Togo? There is for sure always a solution, but this solution would strongly smell like a big bunch of money.

I wanted to continue slightly to the north and visit the popular Wli falls, the most “something” of West Africa, but I quit the idea. The locals, who doesn’t know more than the internet about which border can a foreigner take without being annoyed, tell me it’s not a good idea to take road from Liati (Ghana) to Klouto (Togo). This road appeared at the major one on one poster and on one map. By the way, none of the maps I have show the same roads between the Volta region and Togo.

I don’t know who/what to believe, so I opt for the safest option, Kpedze, even if it involves cycling down by the same road I climbed. The Amedzofe people say there is a border there in Kpedze, after the village. I can reach Kpedze by turning towards Togo in Dzolokpuita. I don’t even have this road on my maps. Anyway, my original plan cannot be successful, because it is really impossible to cycle from Amedzofe to Gbadze and Fume on the other side of the hill. I had spotted wide tracks from Mt Gemi that could work, but the locals told me no 4×4 can take. It would be only possible by hiking down 2 km within rocks and a loaded bike on my shoulder … something really worth many kilometers of detour.

The next day is rainy in the morning. This doesn’t happen often. If the chances to see the rain falling after 4 pm are very high, I have woken up almost every day with a clear sky. But Amedzofe is in the mountains, and it is different. The fog is all over, I cannot even see Mt Gemi. There is another German traveler at the guesthouse and we decide to see the Amedzofe waterfall when the rain stops. Luckily, it stops before noon.

Here again, just getting to the waterfall is tricky. I thought there was one impressive waterfall, but to my questions, locals answer “Which waterfall?“. Hem … here again, who to trust? The small trail on OpenStreetMap (which rocks in this part of Africa)? The man who says one waterfall is too hard to reach in the rainy season? I just want to see that impressive waterfall, but there is no chance knowing which one it is.

We then follow the signs for Ote falls. The path is actually very nice and well maintained. There are kassava plantations all around, until the cliff of the mountains. There, a rope and steep steps take us where the waterfall hide.

After this morning shower, it is time to head to Togo. I reach quickly Dzolokpuita as it is only downhill. It took me a good part of the afternoon from there yesterday. I then turn left and expect to find a border post in 10 to 30 kilometers.

The paved road is more and more narrow and ends up being a sand track. The border post near Kpedze is called Honuta. The exit of Ghana is smooth, with the chief of immigration using my passport to explain the job to a new employee. The two ladies behind the glass are taking one small kid on the desk and forcing him to look at me (which makes him cry)(several times).

I am then out of Ghana. “How far is the Togolese immigration post?“, I ask. “Oh, far, like 1 kilometer“. Well, this is the kind of information of no use. I am also asked if I have my yellow fever certificate, but when I say yes, they don’t ask to see it. Easy and quick.

I am now in Togo. This kilometer is very long. I meet many people, and even pass a village, Klo-Mayondi. Still no immigration post. On my GPS, both Google Maps and OpenStreetMap show me in the middle of nowhere, without any road or place name.

Infrastructure is obviously in a much poorer state than in Ghana. I am finally stopped by a road barrage in Mayondi. I try to be friendly with the police officer as I am not confident I will get a visa issued for the official price (10’000 CFA, 15 EUR).

“- Vous venez pas nous casser notre pays?“, asks the policeman.

I refrain from answering that I can’t do any harm to his country since everything is already broken down. But I am surprised when he says “OK, go“. What? And my visa and my stamp? The immigration post is even further.

So I continue in Togo. I pass more houses, and more people. Everybody is greeting me with “Bonsoir Monsieur” or “Bonne arrivée“. I know this is not standard French but I got used to it, and I feel good to hear it again. The strange feeling is actually to be greeted by something different than “white man”, since I rarely heard Ghanaians saying hello before they shout obroni.

With the polite greetings come also the standard begging of francophone countries. A small kid runs after me to ask “Help me finding a job in Spain!” (seriously?) and an old man makes me stop to say “I fell from a palm tree, now give me money to eat“. I recognize the calling “yevu” for White people in Ewe language. But in general, I sense respect, as in most places before Ghana.

Yet, the immigration office is never coming. What if i missed it? All the roads I see are destroyed and some schools are made of decaying bamboos.

I finally reach it in Kpadapé. When I am about to pass the customs fence in the middle of the road, I learn that the immigration post was 50 meters before. They didn’t bother stopping me. But fortunately, everyone is friendly. Emmanuel Adebayor, called here Sheyi Adebayor, the only Togolese I know, is on the posters in the immigration post, showing him still playing for Monaco.

“– Vous avez un ecritoir?

– Eh?

– Un bic?

– Ah ok.”

I make the 7-day visa (the only visa duration available at the borders) for 10’000 CFA and a passport photo. Togo is a “skinny” country stretching from the coast up to Burkina Faso, but only about 100 km wide. So 7 days are plenty to cross the country.

There is no baggage check, no asking for anything, everything is so smooth. The money changers are gathered under the tree next to the customs, they are friendly and don’t try to cheat me. The customs don’t ask me for anything and allow me to take pictures of the surroundings.

I ask the question that was in my head since yesterday. What if I had entered Togo in Kouto via Liati? The officer replies that I would have to come here first, in Kpadapé. So I avoided a long detour by choosing the correct border post on the first try.

I put on my Togolese flag that I bought in Accra, and I am ready to go in Togo with very good feelings.

And of course, the best part of re-entering a francophone country is the bread: no more square buns called bread when it’s bad brioche! Real baguettes are here. I try a small bread with anise in it and fried corn donuts, it’s simple but delicious.

It has been a short riding day, but heavy enough in terms of adventure. I stop in Kpalimé for the night, a quite large large city in Togo.

Kpalimé is actually a touristic town very close to Ghana, a hiking center for visitors who want to see the mountains. I can tell how popular it is by all the rasta souvenir shops in town.

Strolling in the streets, I meet Clémence working for a NGO in Kpalimé and we have dinner together. Her flatmate, who flew from France recently, had brought saucisson …

Leave a Reply