In Blizreu, alcohol is part of our breakfast and the kids enjoy it too. After Sy, the school principal, and his family have offered us fufu, the old Samuel takes us to his house for another koutoukou session, the locally made sugarcane liquor. The two glasses turn around everyone, including small kids, who drink the strong liquor without even making a face. “It cleans the body from everything“. A mum takes two shots, one for her, and one that goes into the breast for the baby. Now I understand where his title of Chief of the Youth comes from … We have to make our way off our very kind hosts to go cycling before getting tipsy.

On the narrow dirt road until the first town of Danané, we meet two other army checkpoints. We are required to stop so that they register us. It has been already 3 times that we are asked if our parents are still alive (part of the registration process).

The temperatures are much warmer and it is really more humid than in Liberia. There is no reason that the border crossing changed the climatic conditions, but it seems so. The mosquitoes are back as well.

Once in Danané, we celebrate the somehow return to civilization (Ivory Coast has good roads and electricity almost everywhere) with a delicious chicken, served with attiéké, the grated kassava. Maybe, our staple food until now, the plate of rice with a kassava leaf sauce, has benefited an upgrade. We also celebrate ice cold drinks! Since fridges have electricity, they actually cool bottles down and are not used as cooler boxes without ice. We also switch for a local SIM card, and here MTN has a nice offer of 1 week of 2G internet capped to 200 MB for 1500 CFA (just above 2 €).

We meet in Danané an Indian businessman responsible for an alcohol factory who gives us a tour of his bottling facilities. He explains us the purpose of making goods enter Africa from the freeport of Monrovia and transporting then overland to avoid high taxes, even if the Liberian road to Ivory Coast is so bad it can get trucks stuck for a week.

He produces here whiskey, gin and pastis, all made from the same original alcohol: the blue barrels of 250 liters of 96° alcohol. It is roughly 500 USD for such a barrel imported from India, and after dilution and flavoring, it allows him to sell bottles of 40° alcohol for 1 USD per liter. He agrees also that strong alcohol is a good medicine if drunk with moderation, let’s hope the buyers of this alcohol follow his advice before going blind …

The road towards Man is very nice. We move among hills and surrounded by rubber plantations. We don’t cycle much due to our many stops and rests. In the intermediate village of Mahapleu, we stop at a guesthouse to get an estimation of the prices here. The answer is better than our supposition: 2000 CFA (3 €) for the night (without electricity because it is not connected yet). Finally! Finally we are out of those countries where all the dirty hotels are interested only in catering UN and NGO staff for a lot of USDs. So we stop for the night in Mahapleu.

While shopping for dinner, I make a joke to get discounted bananas by requesting the 4 of them for only 50 CFA. But the lady doesn’t seem to understand and add more bananas in the plastic bag … until I realize that I was wrong: 50 CFA is the price for 9 bananas of a decent size, making the banana worth just 0.01 €.

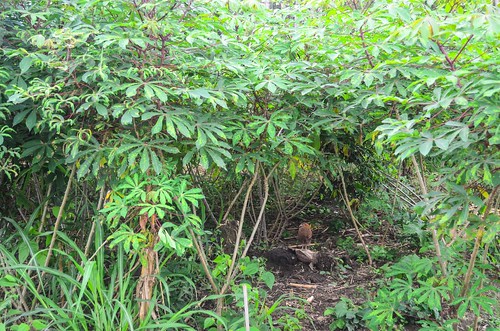

In the morning, Pacôme takes me for a tour of his plantations. Around his house, he grows cocoa, oranges, gombo, kassava, maize, papayas, bananas, rice, and even has a rubber tree nursery. Everything grows in Ivory Coast. There are plantations of coffee and hevea around too. The tour cannot be complete without a degustation of the koutoukou alcohol. The palm wine is called here blanco.

The road is good, almost no potholes, and empty. It goes fast until Man, the capital city of the region of the 18 mountains, which is preceded by a Banbat UN camp.

The Bangladeshi and Pakistani of the UN troops are present in Ivory Coast too. Liberians refugees were hosted here during the war, just like refugee camps have been set up in Liberia for Ivorians. The French army is still present in Abidjan but I don’t witness the anti-French feelings that I had read about. Of course France is accused to strangle and control its former colonies, and taken as responsible for the relatively low economic development (and favoring the corrupted to stay at the head of the government), but I was never attacked with personal comments.

We cycle around Man to see the cascade. Man has an excellent setup, hidden between nice hills, in a region that could be (and was, before the instability reigned with the 2000s) very touristy.

After the waterfall and an ATM stop, we exit Man not on the main road to Duékoué, but on a parallel dirt road, slightly longer. That’s the road paradox: if I am struggling in a country without any good road, I dream of a nice and smooth asphalt surface. Once I reach it, I get quickly bored and take the first bad road available.

What is true is that the scenery and experience are always better enjoyed out of asphalted roads.

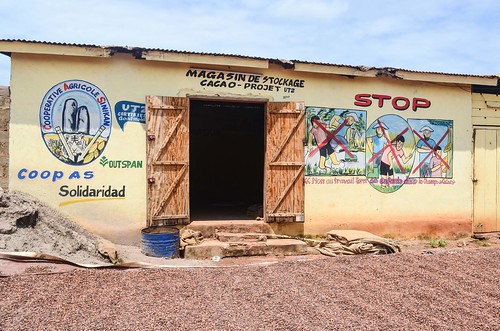

We stop shortly after for the night in Blole, a village with no no tar but with electricity in all houses. Having light at night changes everything and I had almost forgotten about it. There is no proper accommodation, but the chief of village puts us in a room of a very nice house with royal furniture. It is a second house he his building for himself. Dié Thiefaine was awarded the title of the best cocoa planter of the West. It seems cocoa pays well for who owns the land. The coffee is not collected and exported by Ivorians, but by … once again, the Lebanese. Lebanese businessmen are everywhere in West Africa and the money they handle must be really disproportionate with their population (One claims 60% if Liberia’s economy is in Lebanese hands).

We eat again attiéké, this time with chicken feet and gizzards, while enjoying the interesting company. On the top of the very good treatment we receive, the Ivorians we met so far are a pleasure to converse with.

Our first stop of the day is at a village café serving the “café express”: made from Ivorian coffee beans and not Nescafé. Nescafé is present everywhere in French-speaking countries. Even if it has a factory in Abidjan, it wouldn’t be surprising to know the company selling coffee powder coming from Africa, sent to Europe for packaging, and returned to Africa.

At least with the café express, it tastes like coffee. A nearby shops displays the minimum price for sale: 350 CFA (0.50 €) for a KG of café cerise, 600 CFA for café décortiqué.

The next town of Kouibly has plenty of Mauritanians in the market. As usual, Black or White, they are friendly and easily identifiable: look for the people wearing the blue draa and drinking tea, sitting on a carpet on the floor (and selling you goods with discounts making you feel you made a good deal on the moment, until you walk away and realize you got ripped off).

From Kouibly, there are two options: the initial plan, to continue on the main dirt road to Duékoué and find the asphalt there, or the new plan suggested by our Blolé friends: heading east until Vavoua and Daloa via a road that appears on no map, not even Google Maps, and with a river crossing.

It is a risk (are they pirogues operating? Is there really a road beyond the river? We gather as many different answers as questions) but we go for it: it also means we wont see asphalt on the road before a long time.

It looks good in the beginning, with a smooth piste going through plantations. It lasts until the Sassandra river that we cross with the bicycles. We end up in a village without cars but only motorbikes, with no apparent road out.

Before the river, we were confirmed that the smooth piste continues after the river. Now, there is no more piste, and we are warned twice that the forest is dangerous and that we should stick in big numbers and not go through it at night. Now we harvest the consequences of our intrepidity.

The small path out of the village is just big enough for a motorbike. It goes through a cocoa plantation and is very scenic. There are so many green and yellow pods (cabosses). I understand why this road doesn’t appear anywhere, but in the mouth of locals who have never been there: it is because it’s not a road at all.

The plantation is immediately followed by the forest. We enter it at 5 pm and there is no village in it, only huge trees. The forest is never ending and we meet absolutely no one in it. It is dark and has nothing friendly. Now I think we should have taken more seriously the warnings, but it is too late to make a U-turn. We can only cycle as fast as we can and hope for the best.

It gets scary as we still meet no one in two hours and the vegetation is dense enough, leaving only a tiny path with holes of water inside. We reach a bigger track, still of mud, but the night eventually catches us. The forest is never ending. We finally meet 2 local cyclists looking no more confident than us, telling us that anything we could sleep at is too far away. That is not reassuring. They tell us eventually to continue straight until the first campment at the exit of the forest.

We cycle with dynamo lights and headlights, until we face two trucks, side by side, blocking the entire road. They say they are on the way to Abidjan, but one truck has a too weak engine, and they must unload it before continuing. This is super weird as it is a total nonsense to head to Abidjan through this forest in the middle of nowhere, let alone the fact that the engine broke without any slope.

No time for deeper questions as they let us go around the trucks, and we we keep cycling in the night hoping to find this first campment soon.

We reach the end of the forest with great relief, and a man at the first campment tells us to go and see the second one.

It is much better now outside of the forest. Even at night, we can guess there are plantations around and it is more human than the tall scary vegetation. We are welcomed by Olivier in N’gorankro, who takes us to the chief who says: “No problem, you will stay here“.

Great relief. Super great relief in fact, when they tell us we are lucky because people got hijacked in the forest the past two nights.

The villagers proudly introduce themselves as Baoulé, the ethnic group of the first president Félix Houphouët-Boigny. It had been so far the Yokuba people in the Man region. There are so welcoming for two White strangers arriving on bicycles from the dark forest. We are quickly surrounded by the entire village and many kids while we chat. A deserved bucket shower and some attiéké later, I feel good again. They explain that the trucks we saw are people woodlogging illegally the protected forest. Well, the sign explicitly reads it is forbidden, but the locals say it is allowed … we learn more about it with the sous-préfet in Vavoua (next post).

The kids are really curious as some have never seen white skin, and the villagers seem as happy to see us as I am happy to have gotten safe out of the forest. We agree we will rest and discuss more tomorrow with the daylight. After all, we cycled 94 kilometers today on maybe the least practicable roads of the region.

Leave a Reply